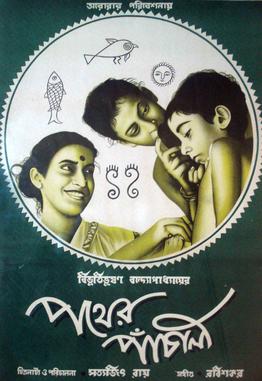

Satyajit Ray’s first film in his glorious Apu trilogy is one of the finest neo-realist films about childhood ever made

Director: Satyajit Ray

Cast: Kanu Banerjee (Harihar), Karuna Banerjee (Sarbajaya), Subir Banerjeee (Apu), Uma Das Gupta (Durga), Chunibala Devi (“Auntie” Indir Thakrun), Shampa Banerjee (Young Durga), Reba Devi (Sejo Thakrun), Aparna Devi (Nilmoni’s wife), Tulsi Chakraborty (Schoolteacher), Binoy Mukherjee (Baidyanath Majumdar)

The filming of Panther Panchali is almost as famous as the film itself. Ray set up on the first day of shooting having never made a film before, working with a cinematographer who had never shot a roll of film before and two inexperienced child actors he had not auditioned. He shot the sequence of quiet, observant young Apu (Subir Banerjeee) and his rebellious older sister Durga (Uma Das Gupta) walk in awed wonder through a field to discover a train whooshing by. Ray later wrote he learned more that day “than from a hundred books”. You can tell: so majestical, magical and mesmerising is the sequence (admittedly the one we see in the film was a reshoot) you can’t believe it was made by a novice. It was the centre-piece of Ray scrapping together funding for the rest.

Pather Panchali was adapted from the novel Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay – in a stunning act of loyalty, Bandyopadhyay’s widow turned down a large sum from a production company for the rights because she had promised them to Ray. Ray turned it into a masterful slice of life, that expressed everything he had worshipped from the neo-realism of Rossellini and De Sica (The Bicycle Thieves, which Ray adored, is surely Pather Panchali’s father) and the detailed, masterful camerawork of Jean Renior (who Ray and photographer Subrata Mitra had witnessed at work on The River). It became Ray’s calling card, and a pivotal moment in Indian cinema, a masterpiece that helped redefine the artistic boundaries of the country’s film industry as well as an award-winning international hit.

It’s a sedate, gentle, un-bombastic but quietly moving and engrossing drama focused on the nitty-gritty of life. Set in a small Indian village in the 1910s, we follow the lives of pre-teen Apu, a dreamer who takes after his Micawberish father Harihar (Kanu Banerjee) and his close relationship with his sister Durga, whose penchant for rebellion and stealing causes no end of strive with their harassed mother Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee). The family lives in poverty and Sarbajaya carries the burden, driven to quiet, repressed despair at the stress of constantly making ends meet and increasingly resentful of Harihar’s elderly relative “Auntie” Indir (Chunibala Devi) who she sees as taking but offering nothing. Despite, this we follow the childish delight Apu and Durga see in the world around them, a world in which darkness eventually (inevitably) intrudes.

Some have argued Ray’s film – and the subsequent films that followed in this landmark trilogy – had such international impact because it fit naturally into international perceptions of India as a rural, poverty-stricken nation. But that’s to do a disservice to the emotional humanism of Ray’s work and the universal themes of childhood, family and the fears of not being able to provide for it.

Pather Panchali, for all the lyrical beauty which Ray shoots it with, is cold-eyed and serious about poverty. There is nothing noble and sentimental about having no money to afford food. The strain of it is carving lines into the face of Sarbajaya, reduced to quietly pawning what possessions they have and frustratingly berating the dreaming Harihar who believes a career as a writer is just round the corner. The shame of poverty is a major theme: Sarbajaya cares nothing if Harihar’s employers are made aware of the family’s desperate need to for the money they owe him, but she will not countenance the shame of accepting charity from neighbours. Debts are repaid as a priority, at several points a relative’s offering of a few rupees is adamantly refused and Sarbajaya is appalled and shocked by Durga’s habit of stealing fruit from a local orchard owned by the village elders.

That orchard was once the property of Harihar – and its more than implied he was conned out of it by the villagers over imaginary debts. Its where we first encounter the young Durga, a delightful, playful and inquisitive child, running free and unashamedly stealing fruit and bringing it home for herself and “Auntie”. Its just another reason for Sarbajaya to resent the presence of this old woman in her household, as well as the close bond “Auntie” has with both her children, with Sarbajaya constantly playing the role of harsh authority figure.

The constant refrain of the train whistle at crucial points from the distant train tracks serves as a reminder of the possibility of change and escape. But it also means to the children a wider world of excitement and opportunity. Pather Panchali is about a child’s eye view of the world – we are literally introduced to the child Apu with a close-up shot of his eye has Durga wakes him for school. Ray’s film carefully follows their experiences and innocence, where every day presents the possibility of adventure and wonder. The struggles of the adults are unknown for them.

Pather Panchali is a great film about childhood. Apu and Durga run through fields, play and fight, share a deep and caring bond. They follow sweet sellers, wonder at the arrival of theatre troupes and brass bands, stare in awe at projected images of Indian landmarks. The entire village and its countryside is a wonderland to them, and the problems of life are something that they don’t need to concern themselves with. Ray shoots the film with a realism tinged with a pre-Tarvoksky love for the beauty of nature: lingering shots follow raindrops on lakes, the willowy blowing of plants in the fields and the movements of nature.

Through it all he draws superb performances from the children, frequently cutting to reaction shots that ground us in a children’s-eye-view of the world. It’s all there in the magic of that pursuit of the train. The freedom of the fields, the joy of running, the mystery of distant sounds and then the impactful glory of the train itself. Alongside this, there is a beautifully judged score by Ravi Shankar that captures both the mood of this humble village life, but also the exurberance of childhood.

It can’t last though. Mortality and tragedy intrude on this life. And just as Ray shot joy with a simplicity that carried a magical pull, so he calmly and unobtrusively observes pain and suffering in a way that will tear your heart out. The film’s episodic look at life becomes darker and more painful, rewarding the patient viewer (and you do need patience for Ray’s leisurely pace) with a powerful connection with the characters – and a final shot that leaves you longing to know what will happen to them.

Beautifully paced, atmospheric and immersed in a world that feels very real, Pather Panchali feels like the work of a master, not the plucky work of debutante. Perhaps that was a result of the nearly two years Ray took to make the film (he couldn’t believe his luck that the children did not noticeably age), allowed him the time few film-makers have to find every single moment of beauty in his story. Or perhaps he was simply that good to begin with. Either way, it became a landmark film – and led to a swiftly answered call for the story of Apu to be continued.