Pasolini’s neo-realist Biblical epic is quite unlike any other retelling ever made

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Cast: Enrique Irazoqui (Jesus Christ), Margherita Caruso (Mary), Susanna Pasolini (Older Mary), Marcello Morante (Joseph), Mario Socrate (John the Baptist), Settimio Di Porto (Peter), Alfonso Gatto (Andrew), Luigi Barbini (James), Giacomo Morante (John), Rosario Migale (Thomas), Ferruccio Nuzzo (Matthew), Otello Sestili (Judas), Rodolfo Wilcock (Caiaphas), Rossana Di Rocco (Angel)

Pasoloni seems a strange choice for a film about Jesus. A Marxist-atheist intellectual? Pasolini had even been jailed briefly for blasphemy after featuring Jesus in his short film La ricotta. But he was fascinated by questions of faith and was a passionate admirer of the classics, from the Greeks to Boccaccio via the New Testament. Pope John XXIII made it one of his missions to reach out to non-Catholic artists (the film is dedicated to him) and Pasolini’s interaction with the Church made him interested in bringing the life of Jesus to the screen.

But on his own terms. Pasolini didn’t want a reverential epic, but something real and human amonf the divine. After scouting the Holy Land and concluding it no longer matched the ideal look required, he would set the film in South Italy. In this he followed in the footsteps of the classic artists, who had frequently transposed events from the Bible to the homelands of their patrons. (And, after all, as Pasolini surely reasoned, not all of the great Renaissance artists could have been passionate believers themselves).

Pasolini also chose his source carefully. Unlike other Bible stories, he would not use all the gospels. Instead he would exclusively dramatise St Matthew’s. Going even further, he would remove the “St” from the title. This was to be one man’s personal view of the story of Christ, featuring only events he reported where the only dialogue spoken would be the words he wrote down. There would be no clumsy modern dialogue, suggested motivations, omnipotent narrator or small talk. The film would play out often in silence, jump from event-to-event and the dialogue would faithfully reproduce the Gospel. There hadn’t been a Biblical epic like it.

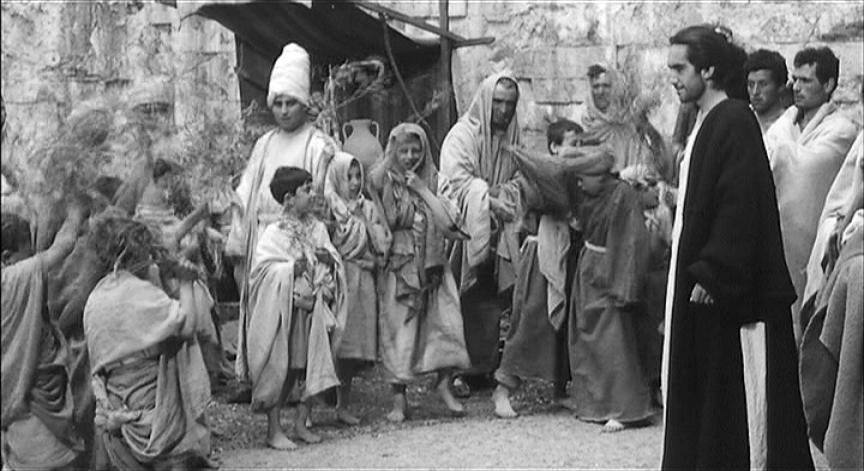

It would also serve as a commentary of sorts on generations of artistic interpretations of the Gospels. The costumes and many of the compositions would reflect different eras of artwork, from Fra Angelina and El Greco onwards. The Romans and Herod’s guards would be dressed in a faux-medieval garb, the Apostles in more Byzantine robes. The execution of John the Baptist looks straight from Caravaggio, the massacre of the innocents like something from Brughel. The sprawling crowd scenes of the great artists would be reflected as much as the smaller intimate moments. The score would be a sea of different religious music, from Bach to Odetta (especially Sometimes I feel like a Motherless Child) via African gospel choir and Blind Willie Johnson.

Pasolini was presenting a reporting of Jesus’ life, that also subtly commented on and absorbed thousands of years of artistic discussion on the same subject. It used visual and aural analogy to convey its story and any question of the “truth” or not was put to one side. It was not a chronicle, but an artistic exploration, where the subjective view removed any theological clashes and implied many more versions were available of the same story.

Pasolini was drawn to Matthew’s gospel as he engaged more with its energy and passion. It carries across here with a Jesus full of contradictions. He can be warm but also angry and passionate. He marches across plains, by turns preaching at and berating his followers, shouting homilies at bewildered farmers. He has the magnetism of a born leader. Fascinatingly, the Sermon on the Mount is filmed in extreme, lonely close-up (with Jesus framed in a Raphael-style pool of light) but his more energetic words against the priests or calling for something near revolution are shown to attract vast crowds (Pasolini’s version of Matthew’s Jesus is perhaps a revolutionary).

The Gospel According to Matthew dug deep into neo-realist Italian film-making traditions. As well as being shot on location, Pasolini recruited a cast of non-professional actors. Jesus would be played by a philosophy student. The rest of the cast would be made up of a sea of professions, from peasants to intellectuals. Unlike Bresson, who drilled his amateur casts mercilessly, they were encouraged to express the wonders their characters witnessed on their faces. Faces of course being Pasolini’s interest – few directors could recruit such a striking range of visages as he could.

Pasolini’s camera-work and film-making style also evolved. The film starts with a series of shot-reverse-shots as a pregnant Mary confronts Joseph. Much of the Nativity plays out in close-up, before the frantic burst of violent energy that is the massacre of the innocents. But as the film progresses, Pasolini mixes his style considerably. Jesus march through the plains is full of something approaching whip-pans. When Jesus preaches, the camera searches for the apostle’s faces with the odd roving mis-turn as if it was searching for them as well.

Shot-reverse-shot is used for the miracles (the element Pasoloini was most uncomfortable about – and embarrassed to bring to the screen), but as the film progresses a more mobile, immersive camera is used. From the Garden of Gethsemane on, the camera becomes almost a face-in-the-crowd, witnessing Jesus’ trial by the priests and Pilate through a sea of crowded heads and moving alongside Jesus through the streets. It follows Judas in a helter-skelter sprint through the plains to his suicide and avoids aerial shots for throwing us in amongst the action. While tipping the hat to art of the past, it is also a hand-held, edgy piece of cinema, putting us in the dirt.

There is much to admire in The Gospel According to Matthew but, it has to be said, the film is also rather slow (the section covering Jesus’ mission and preaching, including the performance of the miracles, in particular drags). The decision to use only the text of the Gospel frequently means the film lacks the sort of drive that spoken dialogue and character can bring. It would almost be superior as a wordless film that made use of captions since much of the dialogue scenes are rigid and the visually least-interesting moments. It’s a film that’s easier to admire than perhaps really love.

But it’s also a very true, fair and intriguing vision of the Gospels, that presents the ‘facts’ as they are and works hard to avoid prejudice and interpretation. Difficult as it may be, at times, to watch it is also challenging and thought-provoking. A melange of interesting filming styles and creative decisions, it has its flaws but many virtues too.