Pasolini’s naughty-boy Boccaccio adaptation, aims for political but in loves with cheek

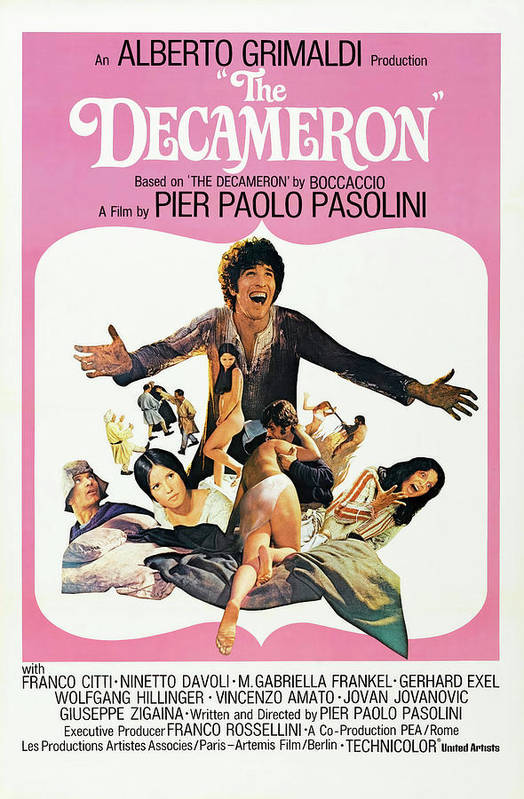

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Cast: Franco Citti (Ciappelletto of Prato), Ninetto Davoli (Andreuccio), Vincenzo Amato (Masetto), Maria Gabriella Maione (Madonna Fiordaliso), Angela Luce (Peronella), Giuseppe Zigaina (German Monk), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Giotto’s Pupil), Giacomo Rizzo (Friend of Giotto’s Pupil), Guido Alberti (Musciatto), Elisabetta Genovese (Caterina), Giorgio Iovine (Lizio)

The Decameron is a collection of a hundred tales written by Boccaccio in the 14th century, which offers a rich mosaic of Italian life from the tragic to the comic. But it also has a reputation for a lot of bawdy naughtiness – and perhaps part of that comes from Pasolini’s cheeky, sex-filled adaptation, with its playful lingering on some of the most rumpy-pumpy filled yarns. Scholars of Boccaccio were appalled in 1971; it’s a gag that I think Boccaccio might have appreciated that today Pasolini’s film is required viewing on Boccaccio courses.

Much like with The Gospel According to Matthew, Pasolini shifted the location to fit his themes. Here most of the tales take place in Southern Italy – Neapolitan accents and dialect abound – and the new underlying theme explore the exploitations of simple, honest peasants by cannier, ruthless people from the richer north. Roughly linking the tales together is a pupil of Giotto – played by Pasolini himself – preparing a fresco in a monastery, inspired (it becomes clear) by the stories which may in turn be inspired by ordinary people he sees on the streets. The Decameron is aiming to be a playful musing on the chicken-and-egg nature of artistic inspiration and the way different artists in different genres can inspire and motivate each other to ever greater heights.

Or at least those themes are there. But they can be hard-to-spot beneath the surface, since The Decameron mostly delights in its array of sexual goings-on, which pretty much tick-offs every taste and inclination you can imagine from masturbation to orgies, as well as darker content like rape and paedophilia. To be honest, for all that Pasolini is an artist thinking earnestly about the classics, he’s also a very naughty boy eager to get a few erect penises into mainstream film-making (and The Decameron was a huge hit in Italy and played in arthouse cinemas the world over). The Decameron, for all its pretentions about art, is also a bit of end-of-pier soft-porn – or a hard-core Carry On.

There is something deliberately amateurish about The Decameron in its scatological humour and the bumpy, rushed nature of its film-making. In common with many Euro films at the time, it makes no effort (either in its Italian or English dubs) to match the words we hear with the movement of the actors’ mouths, with most of the sound having a muffled post-recording session feel to it. The camerawork and editing are frequently jolted and rushed, adding to the bawdy sense of things being thrown together, Pasolini using sped-up film and punch-line jumpcuts to keep up the improvisational energy. It makes the film feel at times like a student revue.

Pasolini shot the film entirely on location, with a cast of actors who were mostly unprofessional. As with many of his films, much of the casting seems to be based on people’s appearances more than anything else. The Decameron has a superfluity of striking faces. Toothy grins or missing teeth, hooded eyes, vacant grins, these faces look like they could have stumbled in from a Brueghel painting. Everyone looks distinctive and this parade of striking faces adds to the film’s wild energy.

It also makes everyone in this Boccaccio cheek and smut stand out. Pasolini’s trick was to argue that the medieval era, in many ways, wasn’t that different from today. He didn’t present it as a high-blown time of men in tights speaking poetry, but one where people were obsessed with money and sex (usually the latter) and showed no shame in chasing it. An era where the medieval world looked dirty, shabby and slightly sordid, rather than what the poets would have us believe.

This informed his choice of stories. When you start with a naïve young man nearly drowned in a pool of shit, you can tell that this isn’t exactly going to be Hollywood medieval epic. Pasolini’s chosen tales involve: a well-endowed gardener pretending to be mute so he can shag a convent full of nuns, a woman boffing her lover while her husband inspects the insides of a large pot, a dying sinner (who we’ve already seen proposition a child for sex) claiming to be a saint, a girl and her lover shagging naked on a rooftop, a monk tricking a man into allowing him to have sex with the man’s wife, and concludes with a man receiving a visit from the ghost of a dead friend telling him that sex is no sin and the angels of heaven say he should certainly give his girlfriend a good pre-marriage seeing to.

Throughout, Pasolini aims to show a world where simple pleasures mix with the exploitation by the rich and powerful of the simple, poor and naïve. It’s a not a theme that comes out all that much, especially since few people are going to remember the political message when we are all much more inclined to focus on the constant in-and-out. The Decameron might want to think it is a grand statement, but its really a great big joke, told by a director who is sort of laughing at us while he does it. It’s a rather juvenile piece of titillation, passing itself off as political statement.

Perhaps that’s why Pasolini felt a bit embarrassed about it all later. After a parade of knock-offs, he effectively disowned the film, claiming low-quality imitators that dialled up the sex even more had missed the point and buried the anti-capitalist message of his own film. Since I can imagine several people watching The Decameron and completely missing the point in the first place, I can’t help but feel he has only himself to blame.