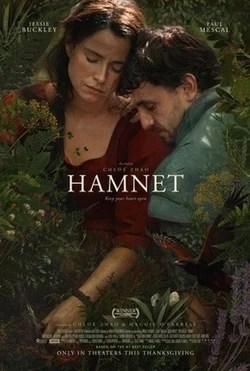

A powerful film about grief that works best in its smaller moments rather than its grand ending

Director: Chloé Zhao

Cast: Jessie Buckley (Agnes Shakespeare), Paul Mescal (Will Shakespeare), Emily Watson (Mary Shakespeare), Joe Alwyn (Bartholomew Hathaway), Jacopi Jupe (Hamnet Shakespeare), Olivia Lynes (Judith Shakespeare), Justine Mitchell (Joan Shakespeare), David Wilmot (John Shakespeare), Bodhi Rae Breathnach (Susanna Shakespeare), Noah Jupe (Hamlet)

“Grief fills the room up with my absent child”. It’s possibly one of the most profound things said about grief and loss. Naturally, it came from Shakespeare who, more than any other writer, could peer inside our souls and understand their inner workings. Grief can strike anyone, and overwhelm them, leaving them hollowed out husks, uncertain how to carry on. It’s a terrifying force that grows to dominate Chloé Zhao’s adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s literary best seller: how it creeps, unexpectantly, into lives that are contented and happy and works to tear down their foundations.

Hamnet imagines the emotional impact of the death of a young boy on his parents: those parents in this case being Will (Paul Mescal) and Agnes (Jessie Buckley) Shakespeare. The film takes us from courtship to marriage, Agnes pushing Will to follow his dreams in London, the birth of their children and death’s seizure of their son Hamnet (Jacopi Jupe). It will have a deep impact on their lives: for Agnes a world of grief and isolation, for Will a cathartic injection of his grief into his new play, Hamlet.

There are many things in Hamnet that work extremely well, not least it’s strong emotional force. Much of the film’s second half is extremely moving, a lot of that from the gentle build of its first half. Grief isn’t an expectant force – it bursts, unannounced into lives. The first half of Hamnet is romantic and optimistic. Will and Agnes’ courtship, two awkward outsiders in a small, rural town, is touchingly portrayed, full of awkward gestures and flashes of joy. Their marriage – over the objections of many, but with the endearing support of Agnes devoted brother, played with real heart by Joe Alwyn – is very happy and they have delightful children who they love very much.

There are tensions: it’s tough to live under the roof of Will’s parents. His father John (David Wilmot) is an abusive bully, his mother Mary (Emily Watson, on excellent empathetic form under a harsh exterior) judgemental. Will is desperate for something more than being a second-rate glove-maker. It’s actually sweet that Hamnet interprets their living apart not due to marital troubles, but a recognition that their love doesn’t need constant contact. Will’s need of London’s bustle is balanced by Agnes’ desire for nature and (ironically) to protect her children from the disease-ridden big city.

It’s the first hour’s playful, graceful unfolding that makes much of the second half hit home. Zhao’s film has an ethereal romanticism, with the camera gliding with patient, unobtrusive warmth around Agnes and Will. While dealing with raw emotions, Zhao brings a sense of magical realism to the film without overplaying her hand. A large part of Agnes outsider status is based on perceptions of her as a witch, who spends her time in the forest building her herbal knowledge (Zhao introduces her with a phenomenal birds-eye shot, nestled womb-like in the roots of a large tree), trusts her dreams and has formed a deep link with a pet hawk. This other-worldly presence in Agnes, carries across in the film’s vibrant, dreamy nature – and shows why Agnes is so drawn to the shy, awkward poet, who similarly feels most alive in his own visions and dreams.

It makes the second half particularly impactful, as the truly shocking death of a child (surely one of the most traumatic child deaths put on screen, devoid of peaceful, Little Nell-like beauty and with Hamnet suffering in prolonged, agonising pain) rips into the happy haven of this life. Zhao’s compassionate distance works brilliantly here, as the film brings us into the pained lives of these bereaved parents, without every once making us feel like intruding voyeurs. Instead, we feel every blow of the film’s perfectly observed exploration of the mundane reality of grief.

A lot of that is also due to Jessie Buckley’s searing performance as Agnes. Buckley is perfect as this slightly jagged, eccentric but determined women who knows her own mind and refuses to bend to others, full of an earthy romanticism. Her vulnerability is there – there is a very moving moment during her twin’s birth, when Buckley rests her head on Watson’s shoulder and weeps pitifully for her (deceased) mummy. But it doesn’t prepare us for Buckley’s perfectly judged raw emotionality. From an agonised, near silent scream at Hamnet’s death, Buckley shifts brilliantly into a shocked quiet whisper that she must tidy up the mess. Over the next few scenes, she collapses into herself, berating her husband with cold fury, wanting him to feel as paralysed with grief as she is. This is a fabulous performance by Buckley, well-matched by Mescal, whose pained soulfulness is perfect for a man processing grief through drama.

But I found the transition of this grief into the creation of Hamlet strangely less moving and more contrived. I’ve always found the attempts to use Shakespeare’s work to fill historical gaps in his biography tiresome. Hamnet studiously ignores that the role was played first by the middle-aged Richard Burbage, rather than a young actor – Noah Jupe, brother to Jacobi playing Hamnet – resembling the late Hamnet. Hamnet carefully re-cuts and selectively stages scenes of Hamlet to present it solely as the tragedy of a lost, sensitive soul. Lord knows what the emotionally enthralled Agnes made of the parts of Hamlet the film doesn’t stage: Polonius’ murder, the abuse of Ophelia, Hamlet making “country matter” gags and so on. Fundamentally it’s a lazy conceit that art can only come by replicating someone’s real experience and is presented in an obvious way designed to score straight-forward emotional points.

Hamnet gets so much right, it hurts that it doesn’t always work. There is an emotional anachronism to the central concept that didn’t land with me: was Hamlet just an inspired, cathartic therapy session for Shakespeare (unlikely since he ripped the plot from an older Danish legend called Amleth)? It lifts me out of things, just as the production and costumes frequently feels a little too clean, a little heritage (even more so considering the raw emotions). Moments of dialogue don’t quite ring true and little things like Shakespeare’s swimming ability (a skill possessed by virtually no one in Tudor England) or its coy dance around confirming Agnes’ historical illiteracy that jar. I’ll also confess I’m irritated by the film’s carrying across of the books conceit in avoiding naming Shakespeare for as long as possible (for almost 100 minutes), while making it clear from quotes throughout exactly who Mescal is playing.

But of course, I know, it’s an emotional fantasia, so perhaps it doesn’t matter that it feels like something shot on a National Trust property. When Zhao’s poetic, observational realism works, it carries real impact. There is a moment at the film’s end when a mirrored overhead shot with the film’s opening, and a look of such radiant hope crosses Buckley’s face, you forgive the manipulative and obvious musical choice accompanying it. Hamnet works best, not in its final showboating act, but in the raw, quiet, everyday moments that show both happiness and grief it gets close to an emotional force that leaves a lasting impact.