|

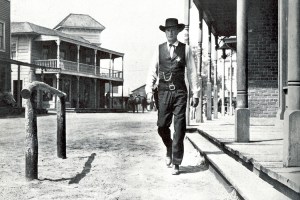

Henry Fonda is here to enforce justice in My Darling Clementine |

Director: John Ford

Cast: Henry Fonda (Wyatt Earp), Linda Darnell (Chihuahua), Victor Mature (“Doc” Holliday), Cathy Downs (Clementine Carter), Walter Brennan (Newman Haynes Clanton), Tim Holt (Virgil Earp), Ward Bond (Morgan Earp), Don Garner (James Earp), Grant Withers (Ike Claton), John Ireland (Billy Clanton), Alan Mowbray (Granville Thorndyke), Roy Roberts (Mayor), Jane Darwell (Kate Nelson)

In John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a journalist says “When legend becomes fact, print the legend”. It could almost be a commentary on My Darling Clementine, a lusciously romantic retelling of the story of Wyatt Earp and his Gunfight at the OK Corrall between the Earps and local cowboy gang the Clantons. John Ford’s film is a perfect slice of Americana, in which the West is seen at its glorious best, and almost no fact in it is true.

In 1882 retired Marshal turned ranger Wyatt Earp’s (Henry Fonda) brother James is killed outside the town of Tombstone, shortly after Earp had turned down an offer to buy his cattle from Old Man Clanton (Walter Brennan), the family patriarch. Earp suspects foul play, but decides to stay in Tombstone as its new Marshal, with his brothers Virgil (Tim Holt) and Morgan (Ward Bond) as his deputies to reinforce the law. In town he meets local gambling man “Doc” Holliday (Victor Mature) and falls for Holliday’s former girlfriend Clementine (Cathy Downs), in town searching for Doc. Will Wyatt find out who killed his brother and find contentment?

My Darling Clementine is almost entirely invented. Virtually nothing in it is true, from the year it’s set (the actual gunfight happened in 1881) to what happens in the actual gun battle. The fates of nearly all the characters have been changed (James, whose death kicks the film off, actually died in 1926) and a host of characters have been invented, not least Clementine herself. The action has been moved to Monument valley from Arizona. Its comprehensive myth-making on screen, with Earp himself changed from an unhappily married man probably “carrying on” with an Irish actress into the pillar of moral decency that is Henry Fonda.

But does it really matter? Not really. If you run with the film has being part of Ford’s tradition of reworking the past of America into a grand origins myth for the United States, the film works perfectly. It’s directed with great visual skill by John Ford, who creates some luscious shots of Monument valley and some glorious skylines that dwarf the actors into the machinery of myth. His visual storytelling is perfect at communicating character, from the boyish leaning back on his chair from the boy scoutish Earp to carefully building the tentative, ]barrier filled relationship between Earp and Clementine.

My Darling Clementine features a romance plot line, but it’s played in parallel with a story of feuding that leaves large numbers of the cast dead. Aside from Earp and Holliday there is virtually no overlap between the romance plot and the events leading to the gunfire. Clementine never refers to it, and you can almost imagine this as two films skilfully and gracefully cut together. Perhaps this is Ford’s intent: this is a film about community in the West, about the building and creation of a town and the shaping of relationships and friendships around it – that just happens to have as well a gang of murderers that Fonda needs to take down.

Tombstone is emerging from the Wild West – at a key moment half way through the film, Earp and Clementine dance (Earp with a surprising grace) at an outside ball to celebrate the opening of a church. It’s just one sign of civilisation arriving in the town, with theatre on the way and even Holliday’s gambling den slowly becoming something a little bit less violent. Earp himself is a reluctant but honest lawman, repeatedly asking at the start “what kind of town is this?” and seemingly deciding to stay to sort the place out as well as find out who killed his brother.

It’s telling in any case that Earp’s reaction to his brother being killed is to pick up a badge not a gun, but then you would expect nothing less from Henry Fonda. Fonda is at his most decent, and bashful, his most just and moral, the embodiment of law and justice. Fonda pitches the performance perfectly, a shy man who knows what’s right, but has the guts to go the extra mile to get it. Fonda also gets some wonderful chemistry from his interactions with Cathy Downs’ Clementine, each scene between them dripping with longing but a sad knowledge that nothing can come of it.

There are a whole host of reasons for that, not least her past relationship with Doc. If there is a second heart to the film, it’s the uneasy semi-friendship that grows between Holliday and Earp. It’s a beautifully judged, wordlessly expressed mixture of regard, respect and suspicion, of two men who have taken very different paths in life but recognise in each other a common world view, a yearning for peace and poetry under the guns. Holliday – dying although you wouldn’t think it considering the hale and hearty look of Victor Mature – is a dangerous man but a fair one, not like the arrogant destructiveness of the Clantons. He’s even able to juggle respectful relations, not least with Linda Darnell’s showgirl. Mature gives a decent performance, hampered by his essential earnest woodenness from really exploring the depths of a TB suffering physician turned gunslinger, but able to express a basic decency and touch of poetry.

It’s a film about small moments between these characters that culminates in parallel with a gun fight that burns out of the clash between the Earps and Clantons. The Earps are of course all thoroughly decent, upright sorts while the Clantons are unclean, unshaven (first thing Wyatt does in the film is get shaved!) types, led by a bullying Walter Brennan. The gunfight is spectacular, but it’s part of one of two films, followed as it is with Earp’s sad departure from the town and the culmination of the unspoken love between him and Clementine. But isn’t that part of the myth? And with its romance, its heroic stand against injustice and its epic sweep and brilliance, My Darling Clementine is a celebration of the myth and power of the West.