|

Michael Caine leads the Old Lags on one last hurrah in the misjudged King of Thieves |

Director: James Marsh

Cast: Michael Caine (Brian Reader), Jim Broadbent (Terry Perkins), Tom Courtenay (John Kenny Collins), Charlie Cox (Basil/Michael Seed), Paul Whitehouse (Carl Wood), Michael Gambon (Billy “The Fish” Lincoln), Ray Winstone (Danny Jones), Francesca Annis (Lynne Reader)

In 2015, a group of old lags robbed a safety deposit company in Hatton Garden. Over the Easter weekend, the gang broke while the facility was empty, drilled through a wall, climbed into the safe and cleared out almost £14 million in cash, diamonds and other goods. The crime captured the public imagination largely because the robbers, bar one member of the gang, were all over 60. This country has a certain nostalgia for rogues, and a tendency towards a condescending affection for the aged. In real life, the only thing remotely charming about these hardened criminals, many of them with extremely violent backgrounds, was their age.

In 2015, a group of old lags robbed a safety deposit company in Hatton Garden. Over the Easter weekend, the gang broke while the facility was empty, drilled through a wall, climbed into the safe and cleared out almost £14 million in cash, diamonds and other goods. The crime captured the public imagination largely because the robbers, bar one member of the gang, were all over 60. This country has a certain nostalgia for rogues, and a tendency towards a condescending affection for the aged. In real life, the only thing remotely charming about these hardened criminals, many of them with extremely violent backgrounds, was their age.

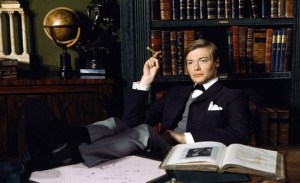

James Marsh pulls together a great cast of actors for his heist caper. Brian Reader, the brains behind the operation, is played with gravitas by Michael Caine. Terry Perkins, the man who cuts Reader out of the profits, is played by Jim Broadbent. Tom Courtenay, Ray Winstone, Paul Whitehouse and Michael Gambon play the rest of the lags while Charlie Cox is the young tech expert who brings the possibility of the heist to Reader’s attention. With a cast like this, it’s a shame the overall film is a complete mess from start to finish.

I watched this film after first watching ITV’s forensically detailed four-part series, Hatton Garden, covering the heist in full detail. That drama was far from perfect, but it was vastly superior to this. The main strength of Hatton Garden was that it never, ever lost sight of the fact that this was not a victimless crime. Real-life small businesses went bust due to property lost in the heist. Families lost priceless, irreplaceable heirlooms. Items of hugely sentimental value have never been recovered. Lives were damaged. On top of that, Hatton Garden stresses the grimy lack of glamour to these thieves, their greed, their paranoia, their aggression and their capacity for violence. Far from charming rogues, they are selfish, greedy old men who fall over themselves to betray each other and are clueless about the powers and abilities of the modern police force.

King of Thieves occasionally tries to remind people that these were hardened career criminals. But it also wants us to have a great time watching actors we love carry out a heist against the odds, like some sort of Ocean’s OAPs. James Marsh never manages to make a consistent decision on the angle he is taking on these men or the crime they carried out. It’s half a comedy, half a drama and the tone and attitude towards the burglars yo-yos violently from scene to scene. The end result, basically, is to let them off with a slap on the wrist.

“It’s patronising” rages Reader at one point at the media coverage of the crime, annoyed at how it stresses their age as if that somehow makes it a jolly jaunt. Never mind that the film does the same. The score contributes atrociously to this, a series of jazzy, caperish tunes that echo the 60s heydays of these violent men (Reader and Perkins had both stood trial for murders, and were lucky to get off) punctured with some cheesily predictable songs. Tom Jones plays as our heroes comes together, and Shirley Bassey warbles The Party’s Over as things fall apart. The old men banter and bicker about the confusions of the modern world like a series of talking heads from Grumpy Old Men and the general mood is one of light comedy.

The film does try and darken the tone in the second half, post-robbery, as things start to fall apart and tensions erupt in the gang. Here we get a little bit of the mettle of the actors involved in this. Jim Broadbent, in particular, goes way against type as Perkins’ capacity of violence (even at a diabetes-wracked 67) starts to emerge. Tom Courtenay’s Kenny Collins emerges as manipulative liar, playing off the robbers against each other. Ray Winstone sprays foul language around with a pitbull aggression. Even Michael Caine roars a few death threats, furious at being betrayed by the gang.

But it never really takes, because the film never throws in any sense of the victims of this crime. Blood is never drawn in this slightly darker sequence of the film. Even the clashes between the gang are played at times for light relief. Anything outside the gang is ignored. The victims? Who cares. The cops? There is barely a policeman in this film who has a line.

The film undermines the whole point it might be trying to make – that these were dangerous men – by succumbing to romanticism at its very end. As the captured old lags await trial, we first see them laughing and joking with each other as they prep for court and then, as they walk towards the dock, the film throws up old footage of the actors from the 60s, 70s and 80s, stressing their romanticism. Look, the film seems to be saying: these were criminals, but they were old fashioned criminals, remember when Britain used to make its own underdog crims instead of being awash with hardened, violent gangs? It’s hard to take. And it’s like the whole film. A tonal mess that finally absolves the robbers who ruined lives and who still haven’t returned almost £10 million of ordinary people’s goods. King of Thieves isn’t charming. It’s alarming.