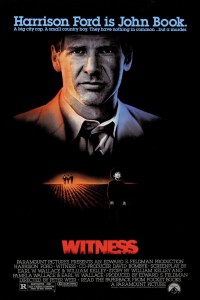

Tom Clancy’s door-stop thriller is turned into an involving conspiracy thriller that makes masterful use of Harrison Ford

Director: Philip Noyce

Cast: Harrison Ford (Jack Ryan), Willem Dafoe (John Clark), Anne Archer (Dr Cathy Ryan), Joaquim de Almeida (Colonel Felix Cortez), Miguel Sandoval (Ernesto Escobedo), Henry Czerny (Bob Ritter), Harris Yulin (James Cutter), Donald Moffat (President Bennett), Benjamin Bratt (Captain Ramirez), Raymond Cruz (Domingo Chavez), James Earl Jones (Jim Greer), Tim Grimm (Dan Murray), Hope Lange (Senator Mayo)

Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan has always been the All-American hero (his slimy, besuited CIA rival even frustratedly snarls “you are such a Boy Scout”). Ryan is almost too-good-to-be-true: pure as the driven snow, incorruptible, a success at everything he does and a devoted family man. What chance does someone like that have in Washington? In Clear and Present Danger, Ryan is dragged into the War on Drugs, unwittingly becoming the front man for an illegal military assault team against the Columbian cartels, ordered by a US President on a vendetta for the death of a friend. When the truth comes out, you’ve got one guess who takes it on himself to save the soldiers who are hung out to dry by the suits in Washington.

We know he’ll do the right thing as well, because he’s played by Harrison Ford. Ryan is basically a blank slate as a character, so Ford’s straight-as-an-arrow everyman decency does most of the heavy lifting to establish who he is. As an action hero, Ford has the chops but his real strength is his ability to look frazzled, scared and muddling through – rather like the rest of us would. Ryan gets in some real scrapes here, from dodging missiles in an attack on a diplomatic convoy to desperately fighting for his life in a timber factory. Ford’s strength as an actor is to be both authoritative and also vulnerable – his willingness to look scared but determined works wonders.

Clear and Present Danger also gives plenty of scope for Ford to employ his other major empathetic weapon: the clenched jaw and pointed figure of moral outrage. He does a lot of both here, a central scene seeing Ryan confronting besuited rival Ritter (played by a weaselly, bespectacled Henry Czerny, the polar opposite of Ford’s clean-cut everyman-ness) earnestly telling him he broke the law and is heading to jail (laughed off). There can’t be an actor more skilled at getting you to invest in someone, to both simultaneously worry about him while being confident he will do the right thing. It’s a rare gift, and Clear and Present Danger exploits it to the max.

Ford is the centrepiece – and main strength – of a competent, well-made conspiracy thriller, directed with a professional assurance by Philip Noyce. It makes a good fist of translating Clancy’s doorstop novel – with its huge complexities – to the screen (although you might need a couple of viewings to work out the twisty-turny, backstabby plot, where wicked schemers turn on their own schemes). Noyce has a special gift for keeping dense technical and exposition scenes lively. At one point he cross-cuts a parallel investigation into a fake car bombing between Ryan (who flicks doggedly through textbooks) and his Cartel rival who employs gadgetry and computers. Plot heavy scenes like this are well-shot, pacey and capturing plenty of reaction shots, even if they only feature characters messaging each other on clunky 90s computers or walking-and-talking in shadowy metaphors.

Clear and Present Danger also successful juggles its Washington shenanigans, with parallel intrigue in its Columbia setting. There ruthlessly charming Cortes (played with a wonderful cocksure suaveness by Joaquim de Almeida) is scheming to takeover his boss’ (a blustering Miguel Sandoval) operation. These plot unfold both together and in parallel, allowing for a little bit of neat commentary contrasting the cartels and Washington. The film manages a bit of critique of America’s thoughtlessly muscular intrusion into the affairs of other countries, with a President turning a blind eye after passing on implicit instructions (but still with a boy scout hero who will sort it all out).

Noyce also pulls out the stops for a couple of brilliantly executed scenes. Great editing, sound design and committed acting makes a scene where Luddite Ryan races to print off incriminating evidence from a shared drive while technically assured Ritter deletes the files, edge-of-the seat stuff. Never before has racing to fill a printer with paper seemed more exciting.

That pales into significance with the film’s centre piece, a genuinely thrilling Cartel ambush on a US diplomatic convoy, with Ryan stuck in the middle. With perfect build-up – from James Horner’s tense score to the skilful editing – the attack (with Oscar nominated sound design) is hugely tense, leaves our heroes terrifyingly powerless and is flawlessly executed by Noyce and his crew. It makes the whole film a must watch all on its own.

It’s surrounded by several other well-handled action set pieces, featuring the Marines sent on a covert mission (and then hung out to dry). As the operation leader, Willem Dafoe plays very successfully against type as a (ruthless) good guy, as Clancy’s other regular character, uber-fixer John Clark. Dafoe also has the chops to go toe-to-toe with Ford, and like de Almedia’s charmingly wicked Cartel-fixer also serves as another neat contrast to Ryan’s decency-with-a-fist.

The film is rounded out by a troop of reliable actors. Anne Archer has little to do as Ryan’s supportive wife, but Donald Moffat is good value as the shifty President (communicating both intimidating authority and Nixonian survival instinct), Harris Yulin perfectly cast as a President-pleasing apparatchik and Raymond Cruz as an ace but naïve marine sharp-shooter. Clear and Present Danger has few pretensions to be anything other than an involving thriller – but that also helps make it a very enjoyable one.