Indulgent, over-long satire that mixes painfully obvious political targets with on-the-nose comedy

Director: Bong Joon-Ho

Cast: Robert Pattinson (Mickey 17/Mickey 18), Naomi Ackie (Nasha Barridge), Steven Yeun (Timo), Toni Collette (Ylfa Marshall), Mark Ruffalo (Kenneth Marshall), Patsy Ferran (Dorothy), Cameron Britton (Arkady), Daniel Henshall (Preston), Stephen Park (Agent Zeke), Anamaria Vartolomei (Kai Katz), Holliday Grainger (Red Haired recruiter)

In 2050, everyone on the colony ship to the planet Niflheim has a job. Even a washed-up loser like Mickey (Robert Pattinson). His job is the most loserish of all: he’s an ‘expendable’, hired to die repeatedly in all forms of dangerous mission or twisted scientific and medical experiments, with a new body containing all his backed-up memories rolling out of the human body printer. The one rule is there can never be more than one Mickey at a time – so it’s a problem when 17 is thought dead and the more assertive 18 is printed: especially as they are flung into a clash between the colonisers and Niflheim’s giant grub-resembling lifeforms ‘Creepers’. Can Mickey(s) prevent a war that the colony’s leader, a failed politician and TV-star Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo) and his socialite wife Ylfa (Toni Collette), want to provoke?

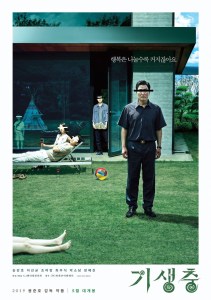

It’s all thrown together in Bong Joon-Ho’s follow-up to Parasite which trades that film’s sharp, dark social satire and insidious sense of danger for something more-like a brash, loud, obvious joke in the vein of (but grossly inferior to) his Snowpiercer. Mickey 17 is awash in potentially interesting ideas, nearly all of which feel underexplored and poorly exploited over the film’s whoppingly indulgent runtime of nearly two-and-a-half hours, and Bong lines up political targets so thuddingly obvious that you couldn’t miss these fish-in-a-barrel with a half-power pea-shooter.

Mickey 17 actually has more of a feel of a director cutting-lose for a crowd-pleaser, after some intense work. Mickey 17 is almost a knock-about farce, helped a lot by Robert Pattinson’s winning performance as the weakly obliging Mickey 17 who grows both a spine and sense of self-worth. A sense of self-worth that has, not surprisingly, been crushed after a lifetime of failure on Earth leads him to series of blackly-comic deaths (the film’s most successful sequence) that has seen him irradiated and mutilated in space, gassed with a noxious chemical, crushed, incinerated and several other fates.

Not surprisingly, there is a bit of social commentary here: Mickey is essentially a zero-hours contract worker, treated as sub-human by the businessmen and scientists who run this corporate-space-trip. It’s an idea you wish the film had run with more: the darkly comic idea of people so desperate to find a new life that they willingly agree to have that life ended over-and-over again as the price. It’s not something Mickey 17 really explores though: right down to having Mickey sign on due to his lack of attention to contract detail (how interesting would it have been to see a wave of migrant workers actively pushing for the job as their only hope of landing some sort of green card?).

Mickey 17 similarly shirks ideas around the nature of life and death. Questions of how ‘real’ Mickey is – like the Ship of Theseus, if all his parts are replaced is he still the ship? – don’t trouble the film. Neither does it explore an interesting idea that each clone is subtly different: we’ve already got a clear difference between the more ‘Mickey’ like 17 and his assertively defiant 18, and 17 references that other clones have been more biddable, anxious or decisive. Again, it’s a throwaway comment the film doesn’t grasp. Neither, despite the many references to Mickey’s unique experience of death (and the many times he is asked about it) do questions of mortality come into shape: perhaps because Mickey is simply not articulate or imaginative enough to answer them.

Either way, it feels like a series of missed opportunities to say something truly interesting among the knock-about farce of Mickey copies flopping to the floor out of the printer, or resignedly accepting his (many) fates. Especially since what the film does dedicate time to, is a painfully (almost unwatchably so) on-the-nose attack on a certain US leader with Mark Ruffalo’s performance so transparent, they might as well have named the character Tonald Drump. Ruffalo’s performance is the worst kind-of satire: smug, superior and treats it’s target like an idiot, who only morons could support. It’s a large cartoony performance of buck-teeth, preening dialogue matched only by Toni Collette’s equally overblown, ludicrous performance as his cuisine-obsessed wife.

Endless scenes are given to these two, for the film to sneer at them (and, by extension, the millions of people who voted Trump). Now I don’t care for Trump at all, but this sort of clumsy, lazy, arrogant satire essentially only does him a favour by reminding us all how smugly superior Hollywood types can be. So RuffaTrump fakes devout evangelical views, obsesses about being the centre of attention, dreams of his place in the history books while his wife is horrified about shooting Mickey because blood will get on her Persian carpet. It’s the most obvious of obvious targets.

It’s made worse that the film’s corporate satire is as compromised and fake as the conclusion of Minority Report. It’s a film where a colonialist corporate elite defers to a preening autocrat, keeps its colonists on rationed food and sex and sacrifices workers left-and-right for profit. But guess which body eventually emerges to save the day? Yup, those very corporate committee once they learn ‘the truth’. Mickey 17 essentially settles down into the sort of predictably safe Hollywood ending, with all corporate malfeasance rotten apples punished. For a film that starts with big anti-corporate swings, it ends safely certain those in charge will always do the right thing when given the chance.

Much of the rest of Mickey 17 is crammed with ideas that usually pad out a semi-decent 45 minute episode of Doctor Who. Of course, the deadly, giant insect-like aliens are going to turn out to be decent, humanitarian souls – just as inevitable as the mankind bosses being the baddies. It’s as obvious, as the film’s continual divide of its cast list into goodies and baddies.

Mickey 17’s overlong, slow pacing doesn’t help. An elongated sequence with Anamaria Vartolomei’s security guard who has the hots for Mickey 17 (every female in the film, except maybe Collette, fancies him proving even losers get girls if they look like Robert Pattinson) could (and should) have been cut – especially as that would also involve losing an interminable dinner-party scene with Ruffalo and Collette. The final sequence aims for anti-populist messaging and action – but is really just a long series of characters saying obvious things to each other. Despite Pattinson’s fine performance – and some good work from Ackie – Mickey 17 is a huge let-down which, despite flashes of Bong’s skill, feels like a great director cruising on self-indulgent autopilot, taking every opportunity for gags over depth or heart. Not a success.