Dreyer’s vampire movie is enigmatic, dream-like, surreal and disturbing

Director: Carl Theodore Dreyer

Cast: Julian West (Allan Gray), Maurice Schitz (The Chatlain), Rena Mandel (Gisèle), Sybille Schmitz (Léone), Jan Hiéronimko (Doctor), Henriette Gérard (Old woman), Albert Bras (Old servant)

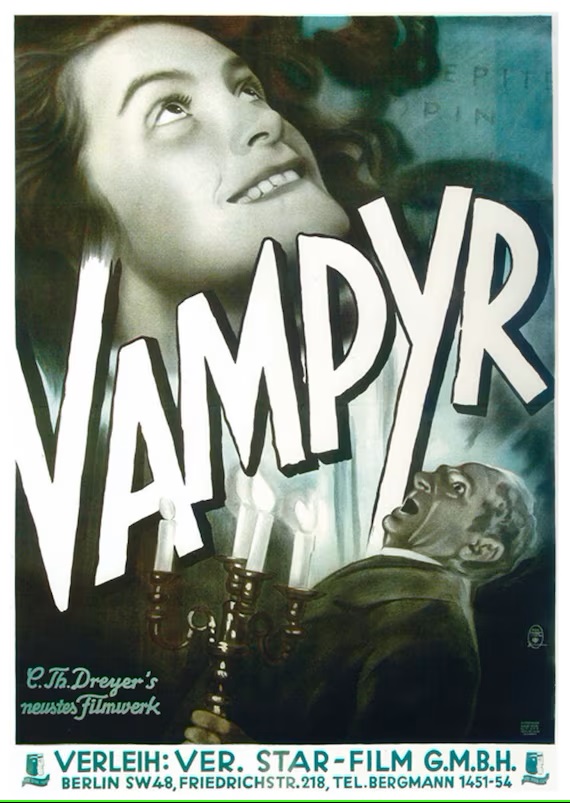

It feels like some sort of bizarre joke. What did Carl Theodore Dreyer direct after The Passion of Joan of Arc? A vampire movie of course! Vampyr for decades was seen as a curious footnote on Dreyer’s CV, so out-of-step with the rest of his filmography that cinematic experts have suggested it was nothing more than a naked attempt to turn a few coins at the box office (something which, like almost all of Dreyer’s work, is spectacularly failed to do). But this is the work of a master visualist film-maker: Vampyr is a vampire movie almost unlike any other, something so dark, surreal and unsettling that will haunt your nightmares.

Inspired by the work of Sheridan Le Fanu, Vampyr (subtitled The Strange Adventures of Allan Gray) follows the arrival of Allan Gray (Julian West) in a strange, secluded village where almost everyone seems to be in a trance, and a series of strange, unexplained events occurs. In the grand house of the lord of the manor (Maurice Schitz), his daughter Léone (Sybille Schmitz) lies dying and her sister Gisèle (Rena Mandel) can’t work out why. When the lord of the manor dies suddenly, West stumbles across what might be the truth: the terrible power of the undead, a mysterious creature that rises from its coffin every night to consume the living and send their souls to damnation.

Vampyr unfolds like something between a dream or a trance. It has lashings of the surreal in almost every scene, and it scrupulously avoids clear or even rational explanations. Events frequently happen for seemingly no rhyme or reason, dreams come to life, shadows gain mysterious powers and everything is designed to unsettle, confuse or mystify us. Camera movements seem designed to disorientate and confuse us about the geography of the locations in the film. It’s shot in a hazy slight blur (a deliberate effect by Dreyer and photographer Rudolph Maté) which adds to the sense that we are halfway between sleep and awake. It adds up to something unsettling, unpredictable but also hauntingly off-kilter.

Vampyr was Dreyer presenting a film the antithesis in almost every way to The Passion of Joan of Arc. He set up his own production company to make it – gaining funding from a Baron Nicolas de Grunsberg (who required that he play the lead role, under the pseudonym Julian West). Joan of Arc was filmed on huge sets, in stark close-up and a static camera, that would bore into every emotion of its characters. Vampyr would be shot on location with a constantly moving camera, performed by actors encouraged to perform as if hypnotised. Where one was about realism, the other would be about occultish fantasy, one about truth the other about concealment.

It ends with Dreyer creating a strikingly originally, deeply surreal and fascinating film, a vampire film in its way as influential as Nosferatu. While Murnau’s film would be unsettling in its painterly composition and the twisted, jittery movements of its lead,Dreyer’s would have the quality of a nightmare. From the start, images to unsettle and disturb the viewer are marshalled brilliantly. Gray’s arrival at his accommodation – with an unsettling, disturbingly long wait for a door to open – is intercut with shots of a mysterious man carrying a huge scythe waiting for a ferry to take him across the river. From such details, Dreyer imposes a sense of twisted unpredictability.

When Gray enters the house he will stay in, the camera seems to whip around the building, making sharp but smooth turns, constantly leaving us slightly disoriented as to where we are. It only gets worse for us as Dreyer throws in the first of a series of sequences where it is almost impossible to tell if what we are watching is real, a dream or something in between. Gray explores a nearby mill, the camera tracking smoothly away from him past a white wall, where we see shadows of a bizarre waltz play out to music, stopped only by the cry of a distant old woman for ‘Quiet!’. In the mill, Gray discovers an array of coffins, strange objects and the sounds of children and dogs – sounds which no one else can seem to hear.

Dreyer continues this unpredictable mise-en-scene throughout the film. The camera constantly focuses on the strange movements of shadows on floors and walls – scenes constantly play out only in shadow. The actors – nearly all of them amateur (and, to be fair, nearly all of them not great) – walk about as if in a daze, robotically delivering lines and as hazy and transmutable as the shadows. Gray even has a literal out-of-body experience, his ghostly double projection reflection separating from his body, to witness a dream (or premonition) of his own funeral.

This sequence is another chilling display of horror, as the ghost Gray opens a coffin to find himself inside – rigid and unable to move – before he finds himself in the coffin, witnessing the lid being screwed in (something we also witness from his POV), but able to see outside through a window in the lid. From this prone, trapped position he witnesses the coffin carried to the church and buried before he awakes. It’s but one nightmareish entombment we see in the film, another character facing the horrific fate of being buried alive under a mountain of freshly sieved flour, his hands grasping hopelessly for freedom above him.

Through it all we see nothing graphic – there is only one brief drop of blood – but everything remains unexplained and terrifying. Doors open seemingly unaided. Discordant sounds are heard (the film’s primitive, intermittent sound actually becoming a benefit for its unsettling effect) and its as if the whole world is collapsing in on itself into a small, nightmareish stumble around a house or garden in unpredictable, hard-to-interpret haze where nothing is as it seems and where everyone seems to be acting under a dark influence.

Dreyer’s Vampyr is horror in its most unexplained, unsettling and ungraphic style. It’s the fear of being trapped in a bad dream you can’t wake from, unfolding in a nightmareish atmosphere of unpredictability and terror where nothing is ever what it seems. Imagery and mood is crucial and Dreyer’s precise but ever-moving camera seems to float unnaturally through all the action. With its touches of the surreal and unpredictable it’s deeply unsettling, haunting and surprisingly effective. Far from a footnote, it shows the depth and ambition of Dreyer’s skill and cinematic vision.