Be afraid of looking in Jordan Peele’s puzzling but less enlightening horror suspense film

Director: Jordan Peele

Cast: Daniel Kaluuya (Otis Jnr “OJ” Haywood), Keke Palmer (Em Haywood), Steven Yeun (Ricky “Jupe” Park), Brandon Perea (Angel Torres), Michael Wincott (Antlers Holst), Wrenn Schmidt (Amber Park), Keith David (Otis Haywood Snr), Donna Mills (Bonnie Clayton)

Spoiler warning: Peele loves to keep ALL the plot details on the QT – so I discuss more than he would want, but hopefully not enough to spoil the plot.

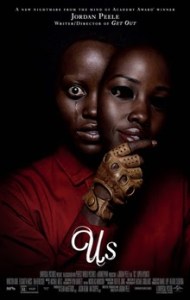

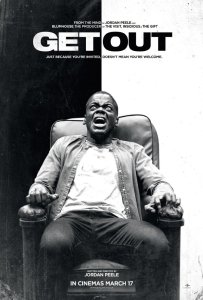

Jordan Peele’s previous horror films brilliantly married up genuine chills with acute social commentary. Plot details have often been kept under wraps – after all half the joy of watching Get Out or Us the first time is working out what the hell is going on. Nope continues this trend, but for the first time I feel this is to the film’s detriment. I actually think Nope would be improved if you know going into it that this was Peele’s dark twist on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (with added body horror). Instead, Nope plays its enigmatic cards so close to its chest that it ends up never having a hand free to punch you in the guts.

Pensive and guarded Otis Jnr (Daniel Kaluuya) – known, unfortunately, as OJ – and his exuberant wanna-be-star sister Em Haywood (Keke Palmer) are trying (with differing levels of enthusiasm) to keep their father’s Hollywood horse handling business alive after his freak death from a coin falling from the sky (everyone assumes it fell from a plane). The business is struggling, with OJ forced to frequently sell their horses to their neighbour, a former child star turned ranch theme-park owner, Ricky (Steven Yeun). Their lives are altered however when they discover a huge UFO living in a cloud near their ranch, sucking up horses (and other animals) and spitting out any inorganic remains. Seeing this as their path to fortune (and in Em’s case fame) they try and capture the UFO on film.

Nope is all about our compulsive need to look. Nothing draws our eyes like spectacle – and what could be a bigger spectacle than a huge saucer in the sky that eats people? It doesn’t matter if we know we shouldn’t, our eyes are drawn up (now imagine if Peele had been able to call the film Up!). We want to be part of the big event, whether that’s seeing the latest blockbuster at the big screen or rubber-necking at a roadside accident. Nope hammers this point home, when it becomes clear you are only at danger from the saucer when you look directly at it. Spectacle literally kills!

This is all an inversion of the mid-West America that starred at the skies in wonder in Close Encounters. There the Aliens capped the film with a glorious light show with awe and wonder from the humans watching. Here the appearance in the sky is a prelude to sucking you up, digesting you and vomiting out blood and bits of clothing a few hours later. Despite this, Ricky tries to make an entertainment show out of the creature (something he, of course, learns to regret), and OJ and Em find little reason to re-think their attempts to capture the animal on screen.

Peele’s film takes a few light shots at social media culture. Of course our heroes’ first instinct is to reach for their phones (they are looking for that “Oprah shot” that will guarantee fame and fortune). OJ at least is largely motivated by the cash influx his struggling business needs – Em wants the fame. But the film still attacks the shallow “main event-ness” of social media, where having the best and most impressive thing to show off (for a few seconds) is the be-all-and-end-all.

Peele remains too fond of these characters to judge them too harshly. But he has no worries about taking shots at the fame-and-money hungry Ricky, or a TMZ reporter who arrives at the worst possible moment and dies begging to be handed his camera so he can record the moment. Arguably Ricky would have made a more interesting lead: a man chewed up and spat out by the fame machine and angling for a second chance, who thinks he’s way smarter than he actually is.

The film opens with a chilling shot of what we eventually discover was the bloody aftermath of the disastrous final filming day of Ricky’s sitcom from his childhood-acting days, Gordy’s Home. Gordy was a chimp living with an adopted family: until the chimp actor snapped in bloody fury. It sets up a sense of danger, but the plot never quite marries it up with the main themes of Nope. Parallels are thinly drawn with Ricky’s attempt to commercialise this infamous tragedy, but it feels forced: the whole section plays like a chilling short story inserted into the main narrative. And the film never explores in detail the lesson from this bloody tragedy, that we underestimate the dangers animals can pose (despite the film being littered with creatures).

Instead, Peele settles for a stately reveal of his plot. It takes almost an hour for the film’s true purpose to become clear, but it lacks the acute and darkly funny social commentary that made his previous films so fascinating while they took their time showing you their hand. Interesting points are made about how black people are (literally) whitewashed out of Hollywood’s history (the Haywoods claim to be descended from the black jockey featured in the first ever moving film made in America). But it’s a political point that sits awkwardly in a satire (about something else!), and Peele overstretches the opening without making the central mystery compelling enough.

There are, however, fine performances from the actors, Kaluuya’s shuffling physique – slightly over-weight, the troubles of the world weighing him down – is matched with his charismatically sceptical looks. Keke Palmer is engaging and funny as his slap-dash sister, and the warm family bond between these two works really well. It never quite makes sense that someone as publicity-averse as OJ would really want to become a social media sensation, but you can let it go.

There is lots of good stuff in Nope – it’s beautifully filmed and assembled and once it lets you in on its plans, it has a strong final act. But its social commentary isn’t quite sharp or thought-provoking enough – people are shallow and love spectacle and social media, who knew – and neither the mystery or the plot are quite compelling enough. It’s told with imagination and Peele has a fascinating and unique voice: but Nope isn’t much more than a solid story well told.