Halting science biopic, that’s really an attempt to make a spiritual sequel to Mrs Miniver

Director: Mervyn LeRoy

Cast: Greer Garson (Marie Curie), Walter Pidgeon (Pierre Curie), Henry Travers (Eugene Curie), Albert Bassermann (Professor Jean Perot), Robert Walker (David le Gros), C. Aubrey Smith (Lord Kelvin), Dame May Whitty (Madame Eugene Curie), Victor Francen (University President), Reginald Owen (Dr Becquerel), Van Johnson (Reporter)

Marie Curie was one of History’s greatest scientists, her discoveries (partially alongside her husband Pierre) of radioactivity and a parade of elements, essentially laying the groundwork for many of the discoveries of the Twentieth Century (with two Nobel prizes along the way). Hers is an extraordinary life – something that doesn’t quite come into focus in this run-of-the-mill biopic, that re-focuses her life through the lens of her marriage to Pierre and skips lightly over the scientific import (and content) of her work. You could switch it off still not quite understanding what it was Marie Curie did.

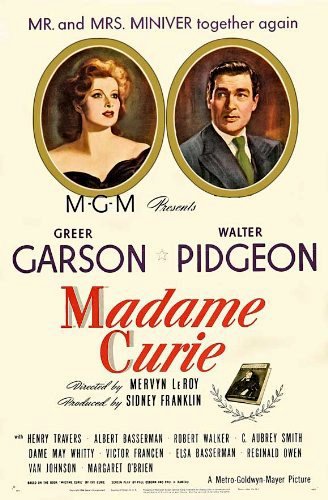

What it was really about was repackaging Curie’s life into a thematic sequel to the previous year’s Oscar-winning hit Mrs Miniver. With the poster screaming “Mr and Mrs Miniver together again!”, the star-team of Garson and Pidgeon fitted their roles to match: Garson’s Marie Curie would be stoic, dependable, hiding her emotions under quiet restraint while calmly carrying on; Pidgeon’s Pierre was dry, decent, stiff-upper-lipped and patrician. Madame Curie covers the twelve years of their marriage as a Miniver-style package of struggle against adversity with Pierre’s death as a final act gut punch. Science (and history) is jettisoned when it doesn’t meet this model.

Not only Garson and Pidgeon, but Travers, Whitty, producer Sidney Franklin, cinematographer Joseph Ruttenberg, composer Herbert Stothard and editor Harold F Kress among others all returned and while Wyler wasn’t back to direct, Mervyn LeRoy, director of Garson’s other 1942 hit Random Harvest, was. Heck even the clumsily crafted voiceover was spoken by Miniver writer James Hilton. Of course, the Miniver model was a good one, so many parts of Madame Curie that replicate it work well. But it also points up the film’s lack of inspiration, not to mention that it’s hard to think either of the Curies were particularly like the versions of them we see here.

Much of the opening half of Madame Curie zeroes in on the relationship between the future husband-and-wife who, like all Hollywood scientists, are so dottily pre-occupied with their heavy-duty science-thinking they barely notice they are crazy for each other. Some endearing moments seep out of this: Pierre’s bashful gifting of a copy of his book to Marie (including clumsily pointing out a heartfelt inscription to her she fails to spot) or Pierre’s functional proposal, stressing the benefits to their scientific work. But this material constantly edges out any space for a real understanding of their work.

It fits with the romanticism of the script, which pretty much starts with the word “She was poor, she was beautiful” and carries on in a similar vein from there (I lost count of the number of times Garson’s beauty was commented on, so much so I snorted when she says at one point she’s not used to hearing such compliments). Madame Curie has a mediocre script: it’s the sort of film where people constantly, clumsily, address each other by name (even Marie and Pierre) and info-dump things each of them already know at each other. Hilton’s voiceover pops up to vaguely explain some scientific points the script isn’t nimble enough to put into dialogue.

It would be intriguing to imagine how Madame Curie might have changes its science coverage if it had been made a few years later, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been eradicated by those following in Curie’s footsteps. Certainly, the film’s bare acknowledgment of the life-shortening doses of radiation the Curies were unwittingly absorbing during their work would have changed (a doctor does suggest those strange burns on Marie’s hands may be something to worry about). So naively unplayed is this, that it’s hard not to snort when Pierre comments after a post-radium discovery rest-trip “we didn’t realise how sick we were”. In actuality, Pierre’s tragic death in a traffic accident was more likely linked to his radiation-related ill health than his absent-minded professor qualities (Madame Curie highlights his distraction early on with him nearly being crushed under carriage wheel after walking Marie home).

Madame Curie does attempt to explore some of the sexism Marie faced – although it undermines this by constantly placing most of the rebuttal in the mouth of Pierre. Various fuddy-duddy academics sniff at the idea of a woman knowing of what she speaks, while both Pierre and his assistant (an engaging Robert Walker) assume before her arrival at his lab that she must be some twisted harridan and certainly will be no use with the test tubes. To be honest, it’s not helped by those constant references to Garson’s looks or (indeed) her fundamental mis-casting. Garson’s middle-distance starring and soft-spoken politeness never fits with anyone’s idea of what Marie Curie might have been like and a bolted-on description of her as stubborn doesn’t change that.

Walter Pidgeon, surprisingly, is better suited as Pierre, his mid-Atlantic stiffness rather well-suited to the film’s vision of the absent-minded Pierre and he’s genuinely rather sweet and funny when struggling to understand and express his emotions. There are strong turns from Travers and Whitty as his feuding parents, a sprightly cameo from C Aubrey Smith as Lord Kelvin and Albert Bassermann provides avuncular concern as Marie and Pierre’s mentor. The Oscar-nominated sets are also impressive.

But, for all Madame Curie is stuffed with lines like “our notion of the universe will be changed!” it struggles to make the viewer understand why we should care about the Curie’s work. Instead, it’s domestic drama in a laboratory, lacking any real inspiration in its desperation by its makers to pull off the Miniver trick once more. Failing to really do that, and failing to really cover the science, it ends up falling between both stools, destined to be far more forgettable than a film about one of history’s most important figures deserves to be.