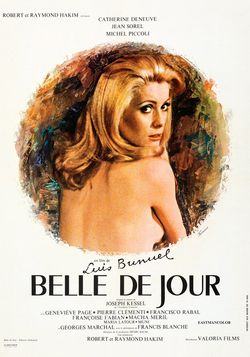

Buñuel’s sensual mix of fantasy and reality, asks intriguing and searching questions with ambiguous answers

Director: Luis Buñuel

Cast: Catherine Deneuve (Séverine “Belle de Jour” Serizy), Jean Sorel (Pierre Serizy), Michel Piccoli (Henri Husson), Geneviève Page (Madame Anaïs), Pierre Clémenti (Marcel), Francisco Rabal (Hyppolite), Françoise Fabian (Charlotte), Macha Méril (Renée), Maria Latour (Mathilde), Marguerite Muni (Pallas), Francis Blanche (Monsieur Adolphe), François Maistre (The professor), Georges Marchal (Duke)

Desire can be a scary thing; a deep dive into the things that excite and titillate us can be deeply unnerving. That’s the heart of Buñuel’s compellingly intriguing Belle de Jour, where dreams and fantasy merge with confused and repressed desires struggling to find an outlet. It makes for a fascinating, unsettling and erotic film, powered by a fearlessly superb performance by Deneuve. Buñuel’s film avoids judgement, frequently inverting lazy moral judgements in a film that flirts with playfulness and dark dangers.

Séverine (Catherine Deneuve) is happily married to Pierre (Jean Sorel) but seems unable to find any sexual satisfaction with him. Sleeping in separate beds, the couple are supportive and loving but chaste. Séverine’s fantasy life though is awash with day-dreams of erotic, sadomasochistic desires in which she is degraded and humiliated, scenarios clearly alien in her marriage. Séverine finds an outlet for her desires by taking an afternoon job as a prostitute in Madame Anaïs (Geneviève Page) high-class brothel, where she can experience an erotic thrill in debasement that she barely understands herself. But can her secret survive the probing of sinister Husson (a brilliantly creepy Michel Piccoli) or her confused fascination with gangster Marcel (Pierre Clémenti).

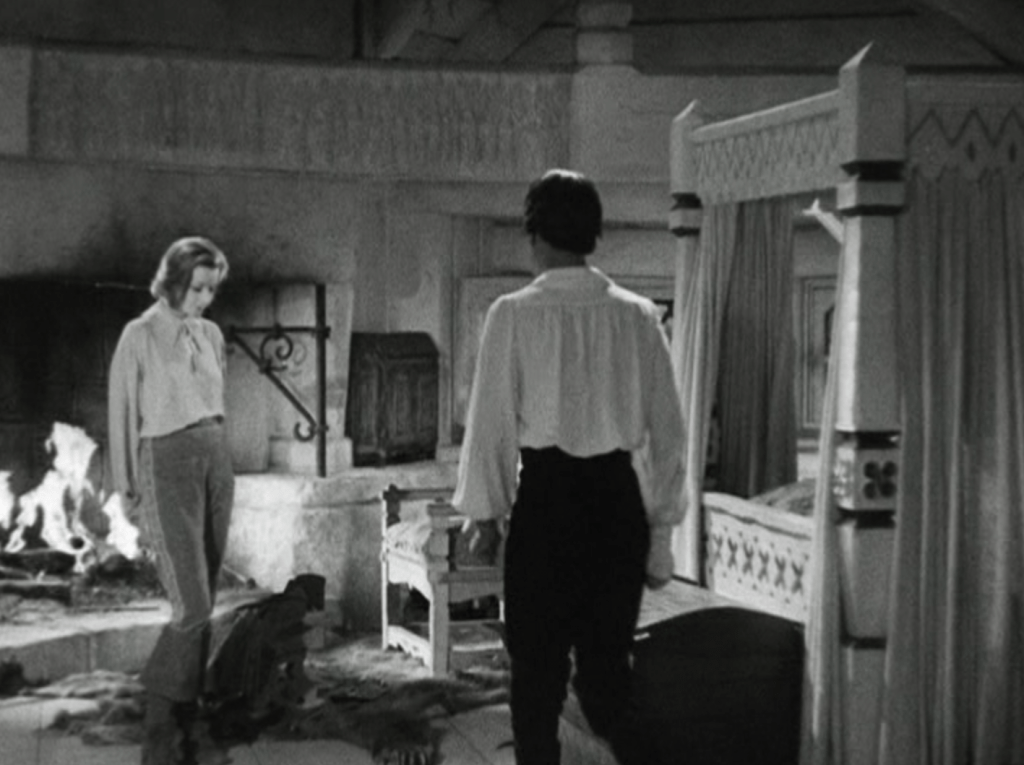

Belle de Jour explores the dark desires many of us hold but never acknowledge – either to the world at large or to ourselves. It’s told with Buñuel’s masterful control, moves with smooth narrative economy and throws our expectations off kilter with carefully controlled switches from reality to fantasy. Buñuel’s unsettling opening shows Séverine and Pierre riding in a carriage through a tree lined country lane, their conversation tinged with hostility. We wonder what film it might be – we probably don’t expect Pierre to order the carriage to stop, demand the drivers drag Séverine from it, take her into the woods, flog her bare back and then allows one of his burly men to have his way with her. Just as we don’t expect the look of pleasure on Séverine’s face.

Fantasies like this re-occur time-and-time again throughout the film, as Séverine’s only way of truly explore sexual fantasies her husband is (presumably) unable to fulfil. In her fantasies she is abused, tied up, has mud flung at her and services men in the full knowledge of her husband. Buñuel presents this, as you might expect (for a man whose foot fetish has become something of a running joke) with a striking lack of judgement or moral ticking off. Instead, it feels more like Séverine is a woman trapped between two stools of seemingly knowing what she might want, but struggling to find the sexual and emotional confidence to acknowledge it. None of this, in any case, has any impact on her love for her husband or the importance she places on their marriage.

Buñuel captures this brilliantly with her hesitancy to follow through on her desire to knock on the door of hostess Madame Anaïs (an excellent Geneviève Page). We watch Séverine dawdle outside the apartment block, doubling back, staring blankly at shop windows and waiting until she cannot be seen and then shuffling up the stairs and back-and-forth outside the door. Buñuel repeats the trick later (with a shot focused on her feet) as she hesitates about whether to push her way through the door again next week.

In the bedroom, Séverine frequently feels awkward and uncertain (even a little embarrassed), which is striking until you realise this is less of the fear factor and more a kink one. She’s fails utterly with the Professor (François Maistre), a client who desires to be punished, a lust completely counter to her own desires. However, she ends a session with a burly Japanese customer, whose physicality terrifies the other girls (he also carries with him a mysterious buzzing box – Buñuel joked he was asked more about the content of this box than anything else in his films), exhausted but with a look of reclining, feline satisfaction on her that we don’t see before or since.

Buñuel’s film slips and slides ever more intriguingly into oblique uncertainty as Séverine explores the further reaches of her sensuality. A fascinating sequence tips uncertainly between dream and reality. Séverine encounters a mysterious nobleman (an austere Georges Marchal) during a casual café pick-up. But his coach drivers are the same as those from her earlier dream (tellingly, Buñuel also makes a Hitchcockian cameo as a café customer –tipping the wink this might not be reality). At the Duke’s home, Séverine lies in a coffin (in another dream call back, the butler is ordered to keep the cats out, the same bizarre cry Séverine made during her woodside thrashing) while the Duke masturbates under the coffin before flinging her out of the house like trash. Fantasy or reality? Is exposure to wider sexual desires expanding Séverine own dreams?

How much has she told Pierre about what happens in these dreams? It’s hard to believe Jean Sorel’s straight-shooting doctor would be as blasé as he appears about a recurring fantasy of his wife on a carriage ride followed of sexual humiliation. Did she just tell him about the first part? Séverine seems determined to shelter Pierre from her desires, part of compartmentalising her inner and outer lives. You could argue the general autonomy and respect he gives her not only powers her love for him, but also runs so counter to her inclinations that she finds it represses all desire for him.

Belle du Jour sees no contradiction between a desire for casual, need-filling sex with strangers and a loving marriage. You could argue Buñuel’s film suggests Séverine’s problems only start when she finds emotional bonds blurring in a fascination with Pierre Clémenti’s brutal, scarred gangster Marcel, who arrives like the violent embodiment of her dreams and who she longs to see again and again. Only when genuine feelings start to intrude, does what she is doing even begin to feel like any sort of betrayal. Buñuel presents Marcel as a destructive raging id, impulsively violent. But he also plays with our expectations of moral punishment for Séverine, throwing in a moment of Pierre studying an abandoned wheelchair with such jarring foreboding it’s easy to see it as a subtle joke on our expectations for Séverine’s expected narrative punishment.

The ending tips back into fantasy, presenting us with a choice of how much we choose to believe is real or not. While Séverine fears Pierre’s discovery of her secret, you can also imagine the shame and humiliation she would feel would also satisfy many of her deeper fantasies, with her fantasies of Pierre routinely berating her as a slut. Buñuel’s brilliant merging of fantasy and reality, with audio and visual hints and call backs that intrude into and loop back over both worlds is brilliantly suggestive.

Belle de Jour also owes a huge part of its success to the sensitive, non-judgemental performance of Catherine Deneuve which is brilliantly subtle and ambiguous, never presenting us with a constantly shifting range of possibilities about Séverine’s emotions. Deneuve is compellingly sympathetic and frustrating in equal measure, perfectly attuning herself to Buñuel’s complex canvas. That is a picture of puzzles and possibilities, that asks us to take deep and unsettling looks at ourselves and our own desires. Buñuel’s gift here is to take what could be red-light zone smut and turn it into something profoundly, challengingly opaque and intriguing.