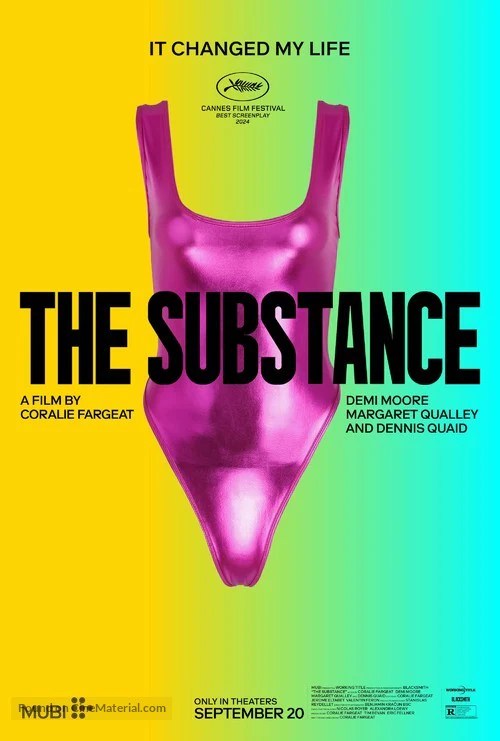

Twisted body horror isn’t quite the feminist statement it thinks it is, but still a unique film

Director: Coralie Fargeat

Cast: Demi Moore (Elizabeth Sparkle), Margaret Qualley (Sue), Dennis Quaid (Harvey), Edward Hamilton (Fred), Gore Abrams (Oliver), Oscar Lesage (Troy), Christian Erickson (Man at diner)

Getting old in Hollywood is not kind. Particularly for women. Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a big star of the 90s, now eeks out a living as exercise queen for a daytime TV show. But TV exec Harvey (Dennis Quaid) decides people don’t want to watch a woman in her 50s and unceremoniously gives her the boot. Fearing a life of lonely irrelevance, miles from the limelight, Elizabeth accepts an invitation to try ‘The Substance’. This black-market drug creates a ‘younger, more beautiful, more perfect’ version of you – birthed from your spine. Taking the drug, Elizabeth spawns Sue (Margaret Qualley), a 20s version of herself who promptly lands her old job on the exercise show.

The two must swop places every week, one living their life (either in obscurity or vicariously enjoying much-lusted after career success) the other lying comatose on the bathroom floor. At first the balance works, but they soon grow to resent each other: Sue despises Elizabeth’s self-loathing bitterness while Elizabeth becomes consumed with envy at Sue’s hedonistic success. Quickly the balanced life between the two collapses, leading to inevitable disaster.

The Substance is one of those films you can pretty much guarantee people will remember about 2024. Pretty much everything in it is dialled up to eleven, a crazy mix of The Picture of Dorian Gray and Cronenberg-body horror (particularly The Fly) by way of David Lynch. Fargeat shoots it with a deliberate grindhouse intensity, revelling in the vast amounts of icky body horror, gallons of blood and guts, often filmed in a mix of dream-like drifting and trashy exploitation.

It’s a sharply directed, extremely intense film from Coralie Fargeat (who also scripts), punchy, vicious and darkly hilarious. It’s also been shot to be almost as uncomfortable to watch as possible. The camerawork is frequently disjointed, full of disconcerting jerky close-up. Nightmare Lynch-style dream horror images pop-up, along with haunting Mulholland Dr style floating heads and Kubrickian homages. Every moment of body horror is accompanied with revolting, squelching sound-effects. You’ve rarely seen anything as intensely, bizarrely OTT as this, the film carefully designed to get audiences either screaming “fucking hell!” or hiding their eyes behind their popcorn.

The film’s most successful moments are these moments of shocking body horror. Created from a host of ingenious practical effects (The Substance surely is destined for a make-up Oscar), the film superbly creates everything from green-fluid soaked birthing scenes to the grim disintegration of various body parts that slowly ages Demi Moore into a wizened babushka to the final hellish Elephant Man by way of the The Fly inspired ending. It’s superbly done, deeply unsettling, but blackly entertaining in its extremity. And The Substance is incredibly extreme, pulling absolutely no punches in this blood-soaked, Angela Carteresque fairy-tale horror.

Fargeat draws an extremely committed performances from Demi Moore, given the sort of acting challenge she never got when she was the biggest star in Hollywood, playing a woman so consumed with ingrained self-loathing and disgust (having so completely swallowed the ideology that your personal value is directly connected to your appearance) that she would rather live as a recluse in the shadow of another version of herself than build a new life. There is an extraordinary scene where a panic stricken Elizabeth prepares for a date with an old schoolfriend (possibly her last chance at a normal life) but is so consumed by self-loathing and doubt about her appearance (painfully ironic, since she of course looks great) that she goes through multiple attempts at make-up up in the movie, each time rubbing it off with such increasing fury that by the end she’s virtually sand-papering her face as if trying to erase herself from existence.

Just as fine is Margaret Qualley as the ‘perfect’ version of Elizabeth, but who has just the same self-loathing and insecurity as the original. It’s a similarly committed performance by Qualley, a carefully studied, surprisingly vulnerable performance while also being ruthlessly ambitious and self-indulgent, which embraces the hyper-sexualised expectations of young women in Hollywood. Dennis Quaid also throws in a fun cameo as a lasciviously camp, OTT executive full of ruthless, heartless bonhomie who sees women only as window-dressing for perverts. After all it’s an industry that forgets: from the opening montage of Elizabeth’s Hollywood star going from eagerly photographed to forgotten, through to the insultingly trivial gift stuffed in her hands as she is dismissed.

But The Substance’s satire is often rather forced and obvious (right down to Quaid’s exec being called Harvey). It feels like it misses a trick by having its only female character being a woman who has so swallowed the ageist views of Hollywood, she literally can’t imagine questioning it. So much so, her clone equally embraces life as a sex object. While The Substance invites us to understand the poison of this world independently, there is virtually no commentary on the unjust sexism within the film. In fact, The Substance so echoes the leering camera angles and pervy shots of the worst kinds of sexist cinema that sometimes it’s a bit hard to see it as satire and (as the camera stares at Qualley’s butt or down her top) more as just reality.

At no point do Elizabeth or Sue make any form of realisation about how they have been indoctrinated to only understand themselves as being worth something so long as they look like a pin-up. While The Picture of Dorian Gray understood the temptations of a selfish hedonism even when we know its wrong and The Fly was all about the damaging impact of ambition, for all its pointed smirking fun The Substance is at heart more of a pulpy gore-show revelling in extreme than a sort of social satire.

In fact the more you watch The Substance the more you think it’s real inspiration is Whatever Happened to Baby Jane and the ‘hag-horror’ of the 60s. A star name of yesteryear, takes on a role that riffs on their loss of youth and beauty, throwing them into an ever more twisted tale of obsession and revenge. You could argue The Substance trusts us to see for ourselves that all this rampant sexism is wrong: but you could also quite happily watch the film and assume it was Elizabeth’s vanity that caused all the problems, not the system that inoculated it in her.

There is another version of The Substance that could match its pulpy love of horror thrills with a bit more of an insightful commentary on gender politics. But the fact the film ends in an explosion of blood that makes The Shining look positively restrained (a sequence that goes on too long in an overlong film), you suspect its real heart is actually in creating shocking images rather than really exploring the issues it wants you to think it is addressing.