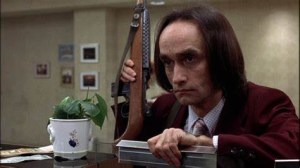

Effective thrills on a well made heist drama with some interesting social points to make

Director: Joseph Sargent

Cast: Walter Matthau (Lt. Zachary Garber), Robert Shaw (Mr. Blue), Martin Balsam (Mr. Green), Héctor Elizondo (Mr. Grey), Earl Hindman (Mr. Brown), James Broderick (Denny Doyle), Dick O’Neill (Correll), Lee Wallace (Mayor), Tony Roberts (Warren LaSalle), Jerry Stiller (Lt. Rico Patrone), Rudy Bond (Police Commissioner), Julius Harris (Inspector Daniels)

Colour coded crooks carry out a crime? Tarantino was clearly a fan of The Taking of Pelham 123. And who can blame him? This is exactly the sort of well-constructed, entertaining thriller Hollywood used to churn out so well. It even manages to mix its cunning crooks with more than a bit of cynical social commentary on the contemporary mess that was New York. It’s grimy, surprisingly hard-edged but with a lean slice of black humour: you can see why it’s a bit of a cult classic.

On the New York City subway, a gang of determined, efficient criminals take control of the front car of downtown train ‘Pelham 1-2-3’ (a train name now banned in New York due to copycat fears!). They are led by polite but utterly ruthless Mr Blue (Robert Shaw) and include nervous train-expert Mr Green (Martin Balsam), loyal Mr Brown (Earl Hindman) and trigger-happy Mr Grey (Hector Elizondo). Their demands are simple: $1million dollars (such humble ambitions these days!) in one hour, or they execute one of their 18 hostages every minute. And no negotiation, no matter how much City Transit Police cop Zachary Garber (Walter Matthau) might try over the radio. With the crooks seemingly having thought of everything, can Garber stop playing catch-up and work out their plan?

You only need to look at the popularity of Die Hard to see what guilty pleasure there is in fanatically prepared criminals trying to get away with it. The Taking of Pelham 123 has all of this. Blue’s team is professional, prepared and have anticipated everything. From calmly telling the passengers how futile any escape attempt would be, to anticipating every single action of the authorities, to delivering (with fatal results) on every one of their promises, these guys have the sort of competence we always sneakly admire in film. Match that with Mr Blue’s strangely samurai-like sense of honour (he’ll keep every deal he makes, despises anger and sadism and respects worthy opponents – even while he emotionlessly executes a hostage) and a bit of you will root for the criminals to get away with it. Right up to, of course, when they start to deliver on their fatal promises.

Of course, it helps that The Taking of Pelham 123 takes some intriguingly sharp pops at the forces ranged against the criminals. The mayor’s ineffectiveness is underlined by having him spend virtually the entire film in bed with a stinking cold. His decision about what to do hinges on how many votes he might get. He resents going to the scene, complaining he’ll get booed (guess what happens!) and is frequently brow-beaten by his more accomplished deputy. When he whines about where they are going to raise the money from (stop to remember for a second what a bankrupt, crime-ridden, mess New York was at the time) it’s even suggested (half-jokingly) he considers cleaning out one of his Swiss bank accounts. Around them many members of the police are heavy-handed, trigger-happy and frequently flustered by the relentless deadlines while the main representative of the train network sees the risk of 18 deaths as an irritating obstacle to an efficient transport system.

This has all been factored into the criminal’s plans. Ask for a big amount, but not so big that the authorities find it politically impossible to deliver. Give a deadline that is achievable but too short to allow anyone the time to make a plan. Count on the general disorganisation of the system being your best ally. Yup The Taking of Pelham 123 is a very 70s crime thriller, when cynical expectations about the efficiency and honesty of the authorities is crucial to the scheme!

Naturally, in a world like this, an awkward looking, scruffy maverick is our hero. Walter Matthau is the man you call for – particularly when the villain is Robert Shaw at his most smooth, clipped and articulate. Matthau’s homespun wisdom and gut instincts are, of course, the only thing the villains haven’t anticipated. It’s Garber’s focus on the people – as opposed to the obsession everyone else has about saving face and passing the buck – that marks him out: that and his authority-shirking cynicism and complete lack of interest in work-place turf battles.

The Taking of Pelham 123 barrels along from there with surprising efficiency and a little dark humour. Some of this humour is even – rather bravely – at the characters own lazy assumptions. One of Garber’s most knuckle-dragging colleagues is seemingly unable to comprehend the idea of a female police-officer. Garber himself isn’t immune: his increasingly rude handling of a group of Japanese transport officials rebounds on him with acute embarrassment when they reveal on departure that they speak perfect English (so understood all his derogatory slurs) and, on meeting his police liaison (Julius Harris) Garber awkwardly fails to hide his astonishment at discovering the authoritative, intelligent man he’s been talking to on the radio is Black (a surprise all too clearly noted by Harris).

Whimsical humour rebounds – not least the impact of the recurring cold of an excellently world-weary and avaricious Martin Balsam’s Mr Green and Garber’s instinctive, polite Gesundheit – among the surprisingly hard-edged violence and no bullets-pulled shootings. But the main thing that ends up compelling you is trying to work out, like Garber, exactly what the criminals are planning and how they intend to get away with it. In that sense, Sargent’s film keeps itself lean, mean and focused and zeroed in on the plot details. A stripped down, always exciting entertainment.