|

Bill Paxon, Kevin Bacon and Tom Hanks are stranded in space in Apollo 13 |

Director: Ron Howard

Cast: Tom Hanks (Jim Lovell), Kevin Bacon (Jack Swigert), Bill Paxton (Fred Haise), Gary Sinise (Ken Mattingly), Ed Harris (Gene Kranz), Kathleen Quinlan (Marilyn Lovell), Chris Ellis (Deke Slayton), Joe Spano (NASA Director) Xander Berkeley (Henry Hunt), Marc McClure (Glenn Lunney), Clint Howard (Sy Libergot), Ray McKinnon (Jerry Bostwick), David Andrews (Pete Conrad), Christian Clemenson (Dr Charles Berry), Brett Cullen (CAPCOM1)

“Houston we have a problem”. Those calmly spoken words coat an ocean of disaster in Ron Howard’s brilliant reconstruction of the disaster-that-very-nearly-was, Apollo 13. Without a shadow of a doubt Howard’s finest film, this is brilliantly tense and hugely engaging that builds an edge-of-the-seat tension around a true story. You can’t watch it without being filled with breathless admiration for the ingenuity of those in mission control and the courage of those in space as they worked together to bring the mission home. Truly “Failure is not an option”.

On a mission to the moon, Mission Commander Jim Lovell (Tom Hanks) and crew Fred Haize (Bill Paxton) and late replacement Jack Swigert (Kevin Bacon) are left desperately trying to salvage their ship after an accident strikes. Meanwhile back in Houston, Flight Director Gene Kranz (Ed Harris) and replaced crewman Ken Mattingley (Gary Sinise) lead a dedicated team juggling every inch of mathematical, scientific and practical knowledge they have to bring the ship home.

Apollo 13 is a masterpiece of reconstruction. Every inch of the NASA space programme is reassembled in perfect detail. Every nut and bolt, from procedures to the interplay between the astronauts and Ground Control. There isn’t a single false note, and every single element of the production, photography and editing is carefully placed to support this total immersion in period. Howard’s technical direction is brilliantly done, intercutting with a fabulous sense of pacing between the crew in space and Ground Control back here on Earth. It becomes one of the most engrossing and involving true-life stories you can imagine.

I love this film. I love every second of it. Every single time I see it – and I must have watched it at least once a year since 1996 – I get wrapped up in the tension and, perhaps even more than that, the inventiveness needed to solve problems in space. The film throws conundrums at us time and time again. The command module needs to be restarted to land the ship – but only has enough power to keep a coffee machine running for a few hours. A vital course correction, that a computer could calculate and perform, needs to be carried out by hand. The weight of moon rocks needs to be replicated in the landing module. And, most brilliant of all, the NASA boffins need to work out literallyhow to fit a round peg into a square hole in order to replace a CO2 filter – using nothing but the pile of equipment on the spaceship.

These problems all need to be solved by people low on sleep, high on stress and – in three obvious cases – stranded, cold and alone in space, and each one is carefully explained by the film’s very natural but highly detailed script and then relayed into nail-biting efforts to solve them. (James Horner’s score also works wonders here, communicating the awe of space and our vulnerability in that black void expertly.) In no other film can the tearing of a plastic bag have you gasping at the impact it could have on life or death.

Added to the impact of this, is the engrossing excitement of watching brilliantly trained professionals tackle the sort of situations that would reduce you or I to sweaty panic. Other than a brief moment of recrimination between Haise and Swigert (authoritatively quashed by Lovell’s “Gentlemen, we are not doing this”), everyone stays more cool, calm and collected than you could possibly expect. This also means that flashes of urgency or emotion carry huge impact in communicating stress: when Libergot stresses powering down the ship is the only way for the crew to survive or Lovell is caught on radio ranting he is “well aware of the Goddamn gimbels” while trying to pilot a ship leaking oxygen through a barrage of debris to a soundtrack of alarms, the pressures they are trying to cope with come thundering home to us.

The extraordinary work of the actors also goes a long way towards the film’s success. If any film cemented Tom Hanks’ everyman quality, it was this one. His Jim Lovell is calm, controlled and extremely grounded, a professional with a realistic outlet, a devoted family man and overwhelmingly ordinary for all the extraordinary things he’s done. Hanks brings the role a huge authority and acres of empathy and relatability. He seems both vulnerable, human and professionally assured. I’d trade both his Oscar-winning performances for this one.

The whole cast follows his lead. Bacon and Paxton are very good as the rest of the crew, juggling moments of fear, frustration and black humour. Ed Harris became a star character actor overnight with his brilliant performance as Kranz, another committed professional who refuses to countenance failure and guides the ground team through super-human efforts, while keeping his own emotions carefully under control. Kathleen Quinlan is impressive as Lovell’s wife, keeping the morale of those left behind as high as she can while barely controlling her own fear. Gary Sinise’s Ken Mattingley channels his resentment at being benched from the mission into a Herculean commitment to bringing them home.

It’s that commitment on the ground that Howard’s film so brilliantly understands. A lesser film would have focused overwhelmingly on the courage of the astronauts alone, and heightened their struggles to pilot the spacecraft and survive. Apollo 13 understands above all that this was a team effort – and the casting and scripting feeds brilliantly into this. No one is the “hero”, no one “saves the day”. Every character focuses on their own small piece of the puzzle and has to trust all the others worked out. The film gives huge amounts of time over to the boffins and geniuses of Mission Control – all brilliantly played by a host of character actors – and its respect for these unsung heroes is as great as it is for Lovell and his crew.

Howard also understands exactly when to up the music, editing and effects and when to slow the film down and let events quietly play out. Moments in space where the actors have to quietly reflect, or when we check in on the fears and concerns of the families back home, contrast perfectly (and carry even more impact) when they sit alongside the scenes of failures and rushes to save lives. As for that re-entry scene… is there any more tense scene in a true story film than that long, long wait to see if Apollo 13 will return from space? There are certainly fewer moments that will get those specks of dust irritating your eyes – I get a lump in my throat just thinking about it.

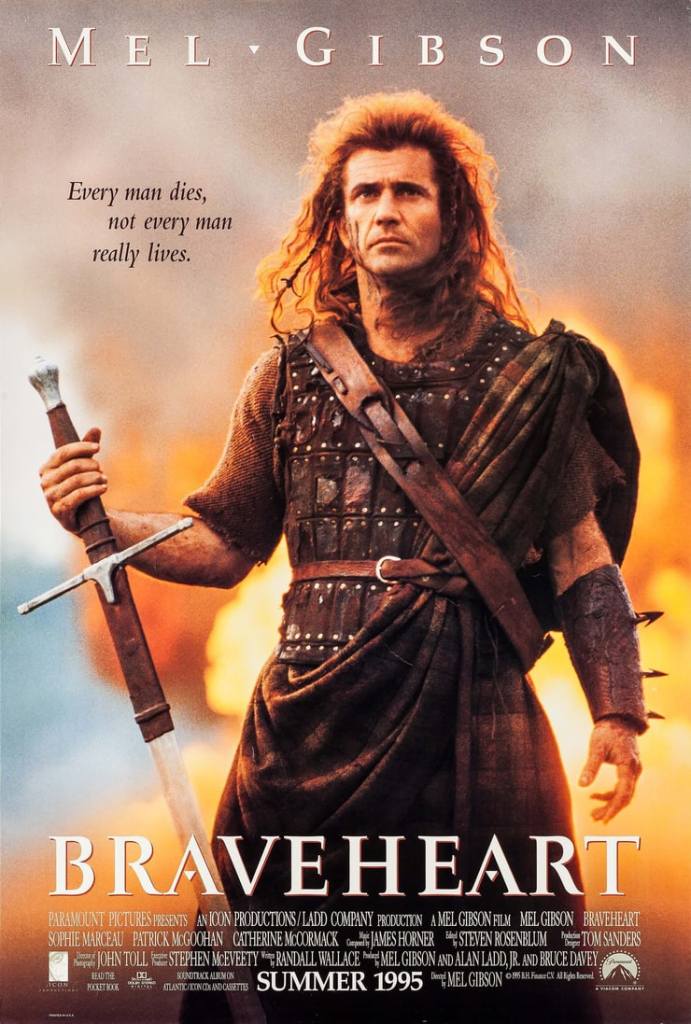

Everything in Apollo 13 is spot on. I would go further and say I’m not sure there is a single wrong beat in it. It’s Howard’s masterpiece – his infamous snubbing for an Oscar nomination is inexplicable, his direction here is vastly superior to winner Mel Gibson’s work on Braveheart. It turns a true-life story into an impossibly tense, deeply involving, hugely emotional story. The actors – some of whom shot for weeks in a “vomit comet” plane to replicate weightlessness, an effect that works superbly – are outstanding. Every single technical aspect of the film is spot on. Its emotional impact is as absolute as the admiration and respect you’ll feel for the real NASA crews that guided this mission home. Apollo 13 is a classic. I can’t imagine anyone not finding something in it to like – not many films you can say that about.