Ozu’s final film feels like a perfect summation of the rich sense of ordinary life in his work

Director: Yasujirō Ozu

Cast: Chishū Ryū (Shuhei Hirayama), Shima Iwashita (Michiko Hirayama), Keiji Sada (Koichi Hirayama), Mariko Okada (Akiko Hirayama), Teruo Yoshida (Yutaka Miura), Noriko Maki (Fusako Taguchi), Shinichiro Mikami (Kazuo Hirayama), Nobuo Nakamura (Shuzo Kawai), Eijirō Tōno (The Gourd), Kuniko Miyake (Nobuko Kawai), Ryuji Kita (Professor Horie)

Ozu’s final film feels like a luscious, beautifully filmed summation of a life’s work. Deceptively quiet, simple and gently paced, like the best of Ozu’s work it throbs with a deep understanding of the quiet joys, regrets and pains in ordinary life, where the march of time can relentlessly change and mould your world. An Autumn Afternoon returns to themes familiar from Ozu past work – you see it as almost a remake of Late Spring (with Chishū Ryū, effectively, in the same role) –with his subtly effective recognition of how each generation echoes and reimagines the one before. It’s a deeply humane film from a director who understood everyday life better than almost any other.

Once again, a man feels pressured to marry off a daughter. Shuhei Hirayama (Chishū Ryū) is a middle-ranking factory manager, whose home is tended to by 24-year-old daughter Michiko (Shima Iwashita). Hirayama’s old school-friend and colleague Kawai (Nobuo Nakamura) suggests an arranged marriage for her. Hirayama quietly lets the subject drift, little motived to shake up his home. His opinions slowly shift as he re-encounters his former teacher The Gourd (Eijirō Tōno), now a down-at-heel noodle restaurant owner, who lives with an unhappy spinster daughter. Does Hirayama sees parallels between himself, Michiko and this pair? Is Michiko bothered either way?

It’s a classic Ozu set-up: the different views and perceptions of the generations, contrasted against each other. In many ways, very little happens in An Autumn Afternoon, but in other ways a whole life-time plays out. Skilfully, with an observing, restrained (Ozu’s final film is stiller than ever) camera, Ozu observes people in the Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter of their lives. In doing so, he captures a particular moment of Japanese history, where pre-War, war and post-war generations confront the world with subtly different outlooks.

In the first darkening of the Autumn of his life, Hirayama is a quiet man with a rich vein of humour. He’s from a generation which sees itself on being more liberal than those before. He meets regularly with a bunch of former school friends, who pride themselves on holding their drink and frequently prank each other in dead-pan comic exchanges. There is a delighted ragging of their friend Professor Horie’s barely concealed sexual glee at his new (younger) wife. They have traditional values (Hirayama assumes marriage will lead to immediate resignation for his young secretary) but enjoy the post-war flourishing of Japan.

Hirayama is comfortable with Americanised Japanese culture, from bottled beers and baseball to American bars and their stools. He drinks too much, make generous offers to others and indulges his children. He’s perfectly happy with the way things are: perhaps because he already fears what his life may be like when his two youngest children flee the nest. It’s a beautifully judged performance from Ryu, genuine, relatable, quietly content but with a subtle sense of sadness and anxiety at change.

There is a sense Ryu’s Hirayama doesn’t want the world shaken, as he has already lived through enough shaking to last a lifetime. He’s a former career Naval officer, who captained a ship in the War. His late wife, it’s implied, died in the American bombing of Tokyo. (Of his children, only two can really remember her, talking about her only wearing trousers during air raids). Bumping into one of his former petty officers, the two men indulge in reminiscences and reflections of what life might have been like in victory (in an American themed bar of all places). Hirayama is drawn to return to the bar again and again, as the barmaid reminds him of his late wife (this small detail would be the entire plot of another film) – although Ryu’s quietly sombreness suggests the memory is to painful to dive into.

But this man contrasts sharply with his children. Hirayama never re-married, and his children have filled the companionship gap in his life. While Michiko matches neatly the traditional view of a Japanese woman as dutiful and guarding of the home (she wears a kimono more than any other female character), his youngest son Kazuo dresses like an American teenager and isn’t afraid to criticise his father. And even Michiko too wants to make her own choices about her life, regardless of the views of others.

The most intriguing contrast though is the marriage between his oldest son Koichi (Keiji Sada) and Akiko (Mariko Okada). Here power dynamics are strikingly different. Both partners work – indeed at one point, Akiko arrives home to find Koichi cleaning and cooking. Decisions are made between them, with Akiko frequently calling the shots. A dispute about Koichi’s plan to spend the excess of a loan from Hirayama on a second-hand set of golf clubs, sees Akiko take firm control of finances (Koichi seems to have inherited his father’s quiet desire not to rock the boat) and has the final say. It echoes, in a way, Professor Horie’s second marriage, where his wife has a level of control over his comings-and-goings that surprises Hirayama and Kawai.

Hirayama may also be quietly disturbed by a vision of what the winter of his life might be like, from ‘The Gourd’, a respected teacher of his childhood, played with a superb desperation and forced good humour by Eijirō Tōno. This once-respected man now works for customers who barely look at him and is totally reliant on a daughter miserable at her life (Ozu quietly watches her break down in tears dealing with her drunken father) and gets embarrassingly pissed at the slightest opportunity when someone else is paying. Considering Hirayama is also a heavy drinker (both men are prone to slumping forward, or swaying on the spot when under the influence) there is a lot that suggests his Winter might not be wildly dissimilar from the Gourd’s.

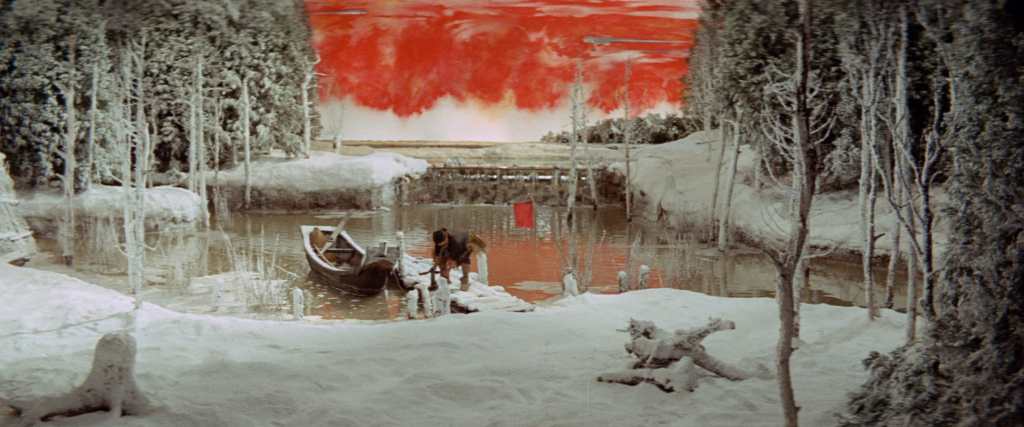

All of these multi-generational issues are superbly explored by Ozu, all without forced commentary, in a film that is a triumph of his distinctive style of low-angle static cameras, transitions that ground us in location, made even more striking by the film’s gorgeous use of colour (especially its reds). And the film leaves it all open to us to interpret. Because there is no right-or-wrong in Hirayama’s situation: should he let his daughter remain or help her move on and embrace her life?

An Autumn Afternoon concludes with one of the most quietly heart-breaking moments in Ozu’s cinema – under-played to utter perfection by Ryu – as Hirayama sits alone, drink swishing around his guts, singing songs of a martial Japan and facing an unknown future that might see him forced to confront the loneliness he has avoided since his wife died. As the final shots complete of Ozu’s final work – a series of cuts to parts of Hirayama’s home – it feels like a perfect final statement from an artist who looked at the small tragedies of life like no other.