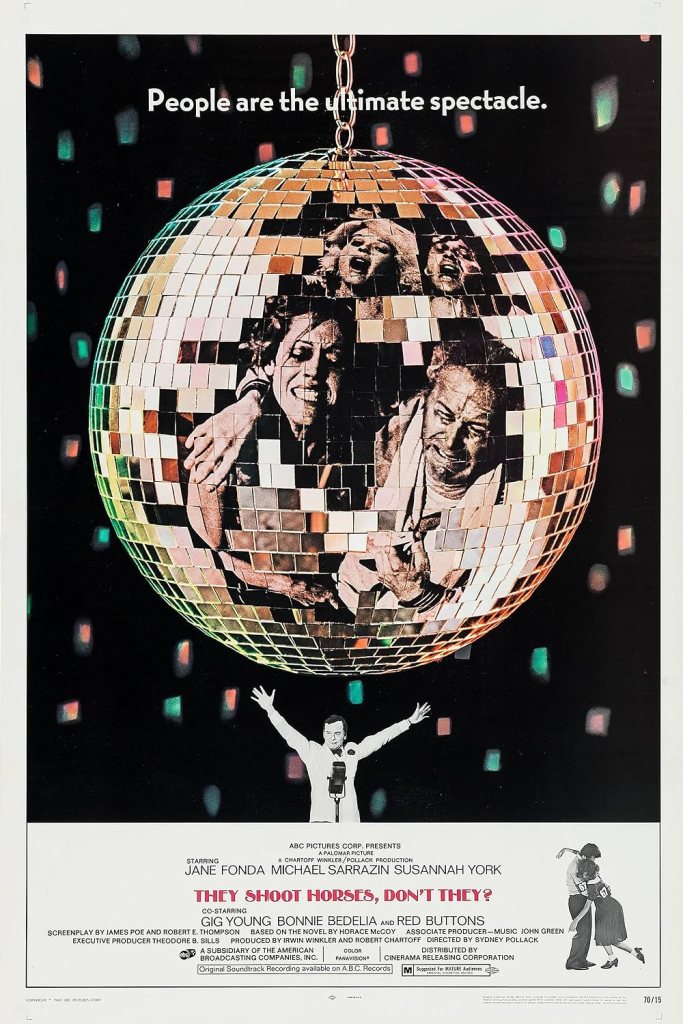

Savage satire on the cruelty of entertainment, heavy-handed at times but also ahead of them

Director: Sydney Pollack

Cast: Jane Fonda (Gloria Beatty), Michael Sarrazin (Robert Syverton), Susannah York (Alice LeBlanc), Gig Young (Rocky Gravo), Red Buttons (Harry Kline), Bonnie Bedelia (Ruby Bates), Michael Conrad (Rollo), Bruce Dern (James Bates), Al Lewis (“Turkey”), Robert Fields (Joel Girard), Severn Darden (Cecil), Allyn Ann McLiere (Shirl), Madge Kennedy (Mrs Laydon)

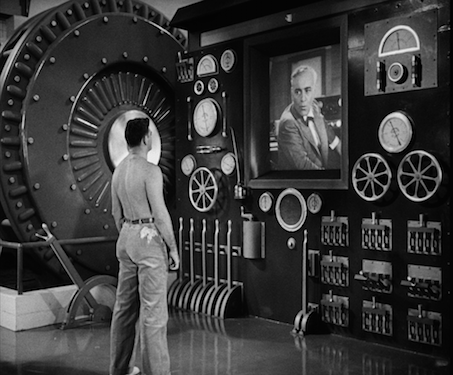

Wheeling out the desperate for entertainment was a mainstay of TV for much of the early noughties with the Simon Cowell factory repackaging human lives for entertainment. But it’s hardly a new phenomenon. During the Depression in 30s America, the country was gripped by a new craze: dance marathons. In exchange for prize money and (perhaps!) a shot at stardom, regular people came off the streets to dance (or at least move around the dance floor) for as long as possible (with short breaks every hour). These shows went on and on, hour after hour, day after day for months at a time, with the audience paying to pop in and gawp.

It doesn’t take much to see how class comes into this. The competitors are the unemployed and out of luck, attracted as much by regular food and a roof over their head. The audience are rich and comfortable, tossing sponsorship bones towards the manufactured ‘stories’ that take their fancy. The event is controlled by a manipulative, alcoholic MC (Gig Young) spinning stories and drama for the crowd. As days turn to weeks the contestants become ever more haggard, drained and physically and emotionally shattered: cynical Gloria (Jane Fonda), homeless Robert (Michael Sarrazin), aspiring actors fragile Alice (Susannah York) and distant Joel (Robert Fields), retired sailor Harry (Red Buttons) and bankrupt farmers James (Bruce Dern) and his heavily pregnant wife Ruby (Bonnie Bedelia).

Pollack’s viciously nihilistic satire throws all these into a hellish never-ending treadmill of physical movement and psychological torture that leaves each character washed out, drained, doused in sweat with sunken, sleepless eyes. You can clearly see the links from They Shoot Horses to Rollerball all the way to The Hunger Games. It’s a grim look into part of the human psyche that, ever since the Colosseum, takes pleasure out of watching the suffering of others for entertainment. The crowded audience – eating popcorn and cheering on their favourites – are as indifferent to the sufferings of the contestants as the organisers with their quack medical teams.

Designed to gain the maximum sense of claustrophobia – once we enter the hall for the dance competition, we never see the outside again for virtually the whole film – the film constantly grinds us down with the exhausting relentlessness of the show. Pollack intercuts this with brief shots of Robert being questioned by the police – moments we eventually realise are flashforwards, making it clear tragedy is our eventual destination. A siren that sounds like nothing less than an air raid warning is repeatedly heard, warning competitors any brief respite they have is coming to a close. The actors become increasingly shuffling, wild-eyed and semi-incoherent in their speech and actions, grimly embodying characters acting on little sleep, in situations of constant strain.

But then that’s entertainment! Part of the thrill for the crowd – whipped up by Gig Young’s showman, a man who oscillates between heartless indifference and flashes of sympathy for his stars (hostages?) – is watching them push on through never-ending pressure. It’s clear to us as well – from their desperate, fixed determination to complete any physical challenge set and the relish with which they consume any food given – that the contestants will tolerate anything just to have, for a few weeks, a taste of something they couldn’t hope to get living on the streets.

Their desperation doesn’t even enter into the moral calculations of those running the show. In fact it’s something that makes them easier to manipulate. Part of the MC’s calculations is creating a relatable story of suffering for the chosen few ‘leads’ any one of which can lead to a triumphant feel-good ending. Potential love-matches are pushed together, sentimental favourites are promoted. Alice’s fine clothing is quietly destroyed by the team running the show because it doesn’t fit a narrative of penniless dreamers. The participants are crafted into “characters”: the ageing Harry as the “Old Man of the Sea”, Gloria and Robert – thrown-together, last-minute partners –as star-cross’d lovers (despite their extremely tense personal relationship).

It all gets too much for the contestants. Serious medical conditions are not unusual – the frequent refrains from the (so-called) medical staff that “we’ve got a dead one” before exhausted, unresponsive contestants are slapped or thrown into ice baths to revive them speaks volumes. When a contestant does indeed die, the event is quietly hushed up for the audience with another feel-good fantasy of noble retirement. Those desperate for a shot at stardom – something they have no hope of getting from a show designed to turn them into drained-out zombies for the entertainment of the masses – are reduced to quivering messes. None more so than Alice – played with a heart-rendering fragility by Susannah York channelling Streetcar Vivien Leigh – who begins the film confidently performing a Shaw monologue and it ends it barely connected to reality.

York’s fine performance is one of several in the film. Young won an Oscar as a MC Rocky, the consummate showman who sometimes surprises us with flashes of humanity (which he clearly drowns with the bottle) before his professional ruthlessness kicks in. Red Buttons is excellent as the rogueish Harry who realises he’s out of depth far-too-late, Bedelia and Dern very good as an experienced couple earning a desperate living from marathons. Particularly fine is Jane Fonda who grounds the film with a gut-punch of a performance of barely concealed rage, deep-rooted self-loathing and brutal, angry cynicism as a woman who understands exactly the show she is in but has no choice but to play along, while hating herself for doing it.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They feel in many ways ahead of its time and for all time – after all, entertainment like this hasn’t died out. Pollack’s film is harshly lit, and his direction is very strong, even if the film does sometimes make its points with a little too much repetitive force. It’s also a film – with its metaphor of suffering horses standing in for suffering people –a fraction too pleased with its own arty contrivance (a slow-mo and sepia tinged opening lays on its symbolism a little too thick, while its flash-forwards yearn a little too much for a French New Wave atmosphere). Michael Sarrazin isn’t quite able to bring depth to the – admittedly deliberately blank Robert – making him an opaque POV character, a role he effectively surrenders on viewing to Fonda.

But despite its flaws, They Shoot Horses Don’t They is a remarkably hard and incredibly bleak film on human nature, which doesn’t let up at all as it barrels to its almost uniquely grim and nihilistic ending. It offers nothing in the way of hope and paints a world gruesomely corrupted and completely indifferent to the thoughts and feelings to the most vulnerable in it. It is ripe for rediscovery.