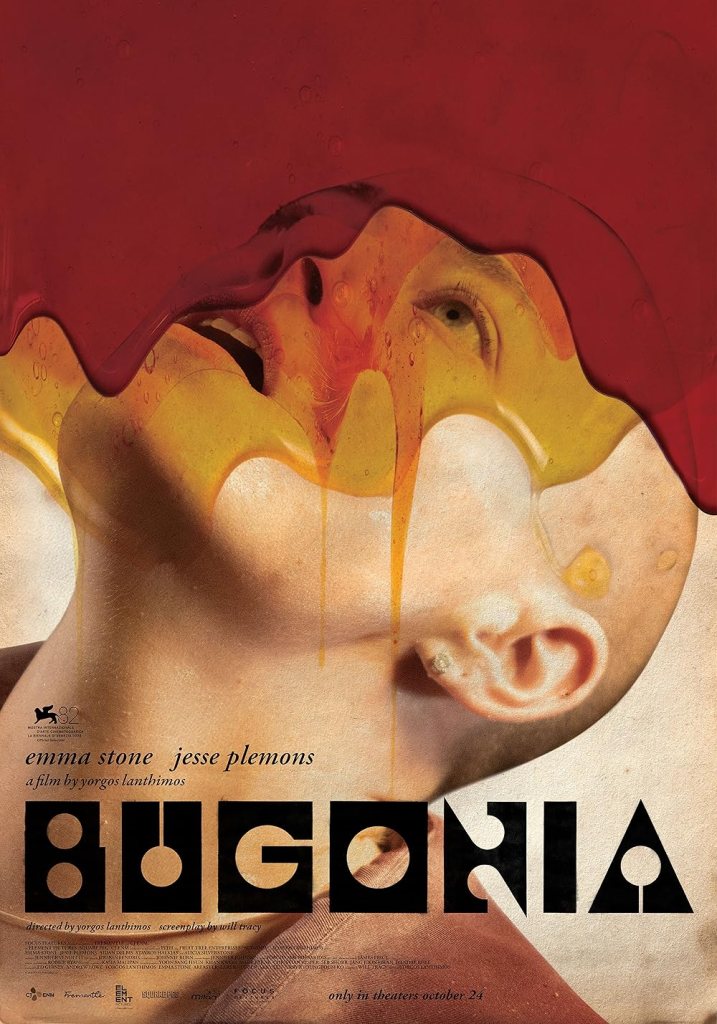

Satire, kidnap drama, politics and more combine in Lanthimos’ partially successful thriller

Director: Yorgos Lanthimos

Cast: Emma Stone (Michelle Fuller), Jesse Plemons (Teddy Gatz), Aidan Delbris (Don), Stavros Halkias (Casey), Alicia Silverstone (Sandy Gatz)

The world sometimes feels like its racing towards hell in a handcart And those on the bottom surely can’t help but look at the super-rich and wonder what on Earth do I have in common with them? But some, maybe particularly beaten down by life, may conclude something different: I’ve got nothing in common with the super-rich, because they are literally not of this Earth. That they are mysterious aliens who walk among us, planning to wipe us out. Bugonia takes a deep dive into the troubled, damaged psyche that can embrace the worm-hole of conspiracy theory, as well as the uncaring platitudes of the mega-companies that (maybe) rule the world.

Michelle Fuller (Emma Stone) is the CEO of Auxolith, an all-powerful pharmaceutical company that operates (at times) right on the fringes of legal. She becomes the target of beaten-down beekeeper Teddy Gatz (Jesse Plemons) and his loyal learning-disabled cousin Don (Aidan Delbris). Teddy is certain Michelle is from the planet Andromeda, that she can contact her mothership through her hair and that her mission is to wipe out mankind. Locking her in the basement of his farm-house, they enter into a mix of interrogation, battle of wills and wits and fluctuating power balances. Is Teddy deranged, vulnerable or misguided? Is Michelle scared victim, arch-manipulator or heartless CEO?

All this plays out, often in tight close-up, in Lanthimos’ jet-black comedy, which is two parts social satire to one part blisteringly nihilistic view of humanity and our future. As Burgonia’s carefully oscillates from one side to another, its political views and stances can be hard-to-perceive, but it certainly suggests Lanthimos has hardly the highest hopes for future. This helps make the film fresh, engaging and challenging. It’s constant cuts from one ‘side’ to the other, also means these two rivals rarely share the same frame, visually imposing their distance and rivalry – Lanthimos even uses non-complementary framing to place them awkwardly together, two people with no common ground.

While Teddy nominally holds the cards as the kidnapper, he’s so clearly such a weak, scared, vulnerable character (often framed weakly within the film) it’s hard not to feel sorry for him. Similarly, Michelle may go through some truly ghastly treatment as Teddy tries to unmask her ‘secret identity’, but remains such a forceful, dominant character (“I’m a winner and you are a fucking loser” she rants at Teddy at one point), framed with such utter assurance, her bland corporate indifference to others and willingness to manipulate the fault-lines in her kidnappers relationships (especially the gentle, child-like Don) never make her feel like a victim but just as dangerous as Teddy.

Teddy’s crazy, flat-Earth-mindset (and Lanthimos punctures each chapter with a view of an increasingly flat Earth, which is at first a darkly comic hat tip and then takes on a second chilling meaning late on) ranting and raving is presented as both darkly funny and also unsettling in how he can use it to justify any violence. Sure, it’s funny that he shaves Michelle’s head and covers her with cream to ‘weaken her influence’, or with gentle earnestness stresses he leads the human resistance to Andromeda (membership currently two). Slightly less funny that he insists he and Don chemically castrate themselves so as not to be seduced, or that pumps Michelle full of over 400 volts to try and unmark her (all while insisting her is a humanitarian, but as an alien Michelle technically has no human rights).

But then Michelle’s corporate coldness is rarely absent. She may remember all her staff’s name with a practised efficiency, but there is a degree of empathy missing in her, replaced with pragmatic hardness. As it becomes clear Teddy’s selection of her is (perhaps) more connected to her drugs companies treatment of his mother (Alicia Silverstone), her blasé assurances that everything was done legally and lack of any real guilt speaks volumes.

Lanthimos always keeps us guessing with Michelle: at moments she will switch from fear and vulnerability, to suddenly snapping back with utter authority, absorbing all the power in the room from the frequently hapless Teddy. Teddy in fact increasingly resembles a lost little boy (he even cycles through town with the relentless pedal-turning speed of a toddler), way-out-of-his-depth and at times all but deferring to Michelle’s advice about her own kidnapping.

Bugonia becomes a dance, not only between truth and fiction, but between two strikingly very different people, one so accustomed to power than even when in a nominally powerless situation they don’t feel anything but a winner, the other a desperate, scraggy haired loser who seems unable to really process what he should do to win a hand where he seems to hold all the aces. To make it work you need two electric actors: Lanthimos has this in spades with two trusted collaborators.

Stone’s ability to switch between corporate fear, desperate negotiation and earnest insincerity are as striking as her ability to keep her character so utterly, eventually terrifyingly, unknowable. In every second of Bugonia you can never be certain exactly what sort of person Stone is playing, her sociopathic assurance both understandable in the situation but also deeply unsettling. Plemons’ gives Teddy a child-like earnestness and desire to do the right thing that underpins his unhinged, ludicrous conspiracy theories, making him someone we both pity and understand is capable of doing terrible things for reasons he can justify to himself. Credit also goes to Aidan Delbris’ affecting performance as the gentle, easily-led Don.

Bugonia may well over-play its hands at points. It’s hard not to expect some sort of twist coming our way – I’m not sure how many people will be surprised by how the film plays out. It’s nihilistic ending feels a little too hard-edged and pointed for a film that hasn’t, until that point, embraced that level of flat-out cynicism. A clumsy introduction of a cop with a shady past is thrown in merely (it seems) to give us another reason to feel sorry for Teddy. Lanthimos’ at points engages, not always successfully, in a level of body horror that wouldn’t feel out of place in the excesses of Cronenberg. But then there are moments of real wit: the paralleled cuts of both Teddy/Don and Michelle going through their fitness regimes, a painfully uncomfortable bolognaise meal that tips into a full-out barney between the two stars, it’s unsettling near-finale in Michelle’s office and the playful realisation that much of the truth was there from the start, but hidden.

Bugonia might be a little too scatter-gun and self-consciously crazy to be a really effective satire, but with two terrific performances and an unsettlingly tense shooting style from Lanthimos (with echoes of everything from Dreyer to Hitchcock) there is enough of interest there to keep your mind bubbling even after it’s hard-hittingly sour ending.