Legendary Soviet Tolstoy adaptation, awe-inspiring in its scale and creative amibition

Director: Sergei Bondarchuk

Cast: Sergei Bondarchuk (Pierre Bezukhov), Ludmila Savelyeva (Natasha Rostova), Vyacheslav Tikhonov (Andrei Bolkonsky), Boris Zakhava (Mikhail Kutuzov), Anatoly Ktorov (Nikolai Bolkonsky), Antonina Shuranova (Maria Bolkonskaya), Oleg Tabakov (Nikolai Rostov), Viktor Stanitsyn (Ilya Rostov), Kira Golovko (Natalya Rostova), Irina Skobtseva (Hélène Kuragina), Vasily Lanovoy (Anatole Kuragin), Irina Gubanova (Sonya Rostova), Oleg Yefremov (Fyodor Dolokhov), Eduard Martsevich (Boris Drubetskoy), Aleksandr Borisov (Uncle Rostov), Nikolai Rybnikov (Vasily Denisov)

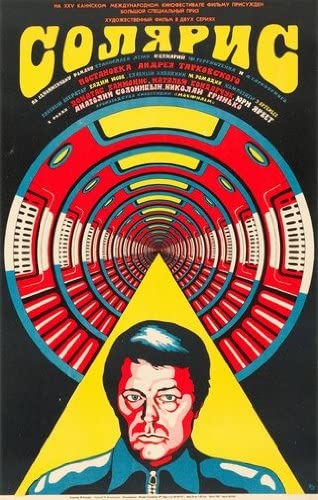

During the Cold War, the superpowers had to fight with things other than nukes. They raced to space. They were gripped by chess matches. And they made rival film productions of Tolstoy’s epic novel. War and Peace, a gargantuan production (it’s really four films and took literally years to make) was the Soviet answer to King Vidor’s War and Peace. If Hollywood thought it could own the greatest Russian novel ever written by making it an Audrey Hepburn vehicle, Mosfilm would take it back. The Soviet War and Peace would treat Tolstoy with the respect it deserved, honouring its literary richness, and putting it on a scale no film had ever seen before.

War and Peace was made with the state’s full backing. Its director would have anything he needed. Rebuild Moscow on the backlot (then burn it down)? Sure. Have historical artifacts from dozens of museums shipped to the film set? Boxed up and ready. Use tens of thousands of troops – and three war-hero Generals as assistant directors – to restage the battles of Austerlitz and Borodino? Thousands of horses were shipped to the set, while seamstresses worked on over ten thousand costumes. Moscow even created an arsenal of functioning cannons which shot 23 tons of gunpowder for the recreated battles. It’s no exaggeration that no film before or since could match this for scale. Avengers: Endgame eat your heart out.

To direct this gargantuan operation, Mosfilm and the Ministry of Cuture selected Sergei Bondarchuk, relatively young in his early 40s, over the seasoned veterans who expected the gig. Bondarchuk was by all accounts a hard taskmaster, who fought, bickered and bullied practically everyone on set (burning through three cinematographers), but also had a gift for marshalling effectively a small nation for years (though not without at least two heart attacks, one of which left him clinically dead for five minutes). He also had the chutzpah to audition nearly every actor in Russia before deciding the best man for the leading role of Pierre Bezukhov was none other than… Bondarchuk himself (for good measure, Bezukhov’s seductive screen wife would be played by his own wife Irena Skobtseva).

War and Peace could have gone two ways: its scale could have flattened a lesser director or led to the sort of middle-brow, stale traditionalist fare Hollywood hacks churned out for years. Instead, Bondarchuk was fascinated by the possibility of the medium and swept up in playing with the cinematic tricks explored by his heroes and contemporaries. War and Peace is a strikingly unique, often discordant, meditative film, full of visual invention that pushes the boundaries in the most inventive ways to present its colossal scale.

You can see traces of Abel Gance’s Napoleon in its evocative use of double exposure images (showing ghost like echoes of people appear in frame, most notably the near-death experience of Andrei Bolkonsky) and its extreme close-ups, not to mention the more obvious triptych homages for key moments (such as Napoleon and Alexander III’s meeting at Tilsit). Bondarchuk’s influences went wider than that: there is a social realist immediacy in several scenes, with their jittery camera-work, throwing us into confusing battles, that wouldn’t look out-of-the-ordinary among the Italian Neorealists. There are patches of Welles and Lang in the sweeping camerawork that stress the scale and geography of the sets. Panoramic aerial shots dial up the most ambitious work of Murnau and Gone with the Wind. Bondarchuk’s decision at key emotional moments to fade out all sound except for ambient noises, such as drips, breathing or birdsong feels like he’s been studying Tarkovksy – as does the beautiful, lingering shots of nature. Bondarchuk wasn’t just going to make a stately coffee-table book: he fused distinctive flourishes from the great film-makers, to wonderful effect.

In addition, Bondarchuk (also the co-screenwriter – did his chutzpah influence that similar wunderkind Kenneth Branagh, both obsessed with tricksy, inventive camerawork) wanted to pay tribute to Tolstoy. What’s remarkable about War and Peace is how much of Tolstoy’s meditation on the meaning of life is in the film. Sure, there are cuts – Nikolai Rostov, Sonya and Maria Bolkonskaya are reduced to the bare bones – but this film finds a great deal of time for its characters to muse (either in sometimes portentous voiceover, or a deep-voiced omniscient narrator) over the meaning of life, the quest of happiness and the nature of decency and nobility.

In fact, this is a particular surprise since this version War and Peace had its roots as a patriotic demonstration of Soviet film-making might. It’s particularly striking then that it ends with a sequence that stresses how ordinary soldiers (French and Russian) have more in common than not and how much links mankind together than drives them about. This is not pro-Soviet propaganda.

Not that War and Peace doesn’t take a few potshots at the effete, selfish rich, sitting in comfort while soldiers fight at the front. But it also finds time for the Rostov’s decency and self-sacrifice for and it doesn’t stint on the grandiosity of Tsarist Russia. A ballroom scene, site of Natasha’s meeting with Andrei Bolkonsky, is stunningly staged. In a huge mirror-laden ballroom, Bolkonsky’s camera bobs and weaves between dancers. Cinematographer Anatoly Petritsky suggested he filmed it while roller-skating, a genius innovation which creates a visual dancing effect as well as allowing us to be right among the literally hundreds of grandly costumed dancers (Bolkonsky skated alongside Petritsky, at times holding a fan slightly before the camera, to add to the effect).

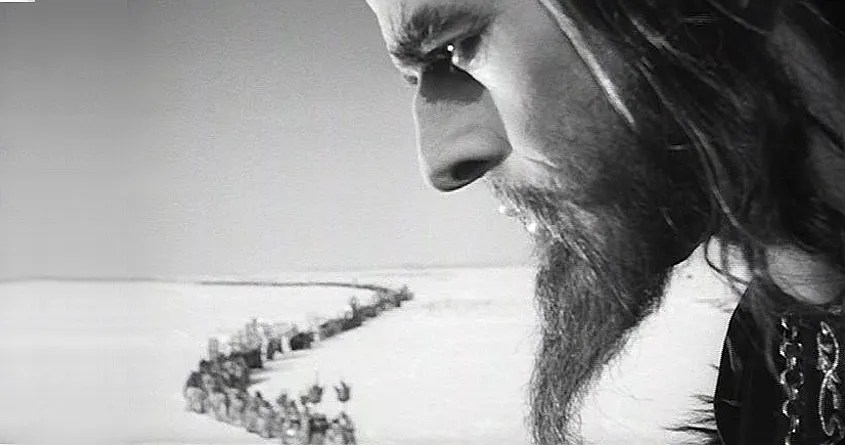

The magnificence of this often gets forgotten in the awe-inspiring spectacle of the Russian military backed battles. Bondarchuk enlisted the Soviet Air Force for stunning, wide-angled aerial shots that revealed the stunning dimensions of the recreation. Petritsky also introduced a series of diving crane shots – like the camera has been set on a zip wire – that fly down from the heights into the battle’s chaotic maelstrom. (The battles are, as per Tolstoy, confusing messes where no one knows what’s going on but everyone pretends to be in charge). These battle images virtually redefine epic, mind-blowing in their scale – and the managerial and artistic force that must have been needed to organise and capture them all on screen as exquisitely as they are.

The same goes for the burning of Moscow, a dizzying outburst of flame, co-ordinated tracking shots (following Pierre through the burning wreckage) while crowds of extras run and panic. War and Peace also follows Tolstoy in being perhaps one of the grandest scale, anti-war films ever made. There are no real moments of heroism in the battle, soldiers march into injury and death and Bondarchuk frequently pans the camera across mounds of bodies or soldiers left mauled and dying on the ground. The retreat from Moscow sees Hellish suffering for the French, but that is balanced by the horrifying executions of civilians they carry out in Moscow, terrified men and boys led to stakes and gunned down in hard-hitting slow-motion. War and Peace doesn’t shy away from the suffering, pain and death that war brings, with very little glory or pride to show for it.

It’s also a film that’s often strikingly well-acted. Bondarchuk may be too old for Pierre, but his thick-set frame is perfect and his soulful eyes beautifully capture the character of a would-be-philosopher with no purpose. Vyacheslav Tikhonov makes Bolkonsky an imposingly distant man hiding his fragility. Perhaps most strikingly, ballet dancer Ludmila Savelyeva is a radiant Natasha, waif-like but bursting with energy and life, who tackles better than almost anyone else an impossibly difficult character. Bondarchuk frames her perfectly, back-lit to focus on her expressive eyes.

At times there is almost too much to everything in War and Peace. Bondarchuk is at times almost constitutionally incapable of shooting a simple scene, a relentless inventive energy that is perfect for the war but sometimes exhausting for the peace. The all-consuming screentime given to the scale of the battles and balls does eat into the time allowed to character and plot. But this is like complaining about being uncomfortably full after a generous rich meal. There is so much in War and Peace Bondarchuk gets right: from its respect to Tolstoy, but as an intellectual not as heritage figure to its stunning visuals, in every minute of its great length there is something to admire, thrill and strike you with awe. In this instance, the Soviets proved they could do Tolstoy better than the Yanks.