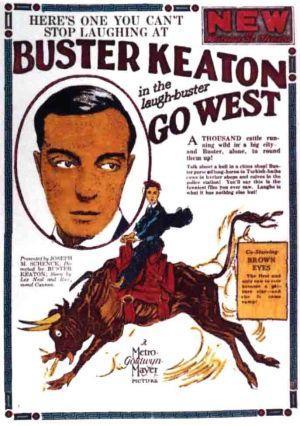

Keaton meets his finest leading lady – a cow – in this adorably charming comedy

Director: Buster Keaton

Cast: Buster Keaton (Friendless), Howard Truesdale (Ranch owner), Kathleen Myers (Ranch owner’s daughter), Ray Thompson (Ranch foreman)

Keaton had been unconvinced by Seven Chances, the theatrical farce he’d been asked to film that saw him chased left, right and centre by women. Perhaps his reaction to playing a somewhat cold man pursuing and pursued by ladies persuaded him to try something completely different. What if he could make a film where he removed the “romantic” girl from the equation altogether? Could Keaton make an affecting comedy where his character’s strongest bond is to a cow?

Go West is Keaton back to his best, a glorious Western spoof (a happy return to the grounds of Our Hospitality). Keaton is Friendless, a hard-working guy adrift in the cut-and-thrust of the world. So much so that, visiting New York, he is literally trampled by bustling crowds. He heads out West to try his luck, becoming a ranch hand on a farm. There he finally meets someone who sees him as a friend – ‘Blue Eyes’, a cow who like him is an outcast from the herd. For the first time both of them has a friend – but what will Friendless do when Blue Eyes is to be packed off to a Los Angeles slaughterhouse?

You would never think that a man and a cow could be as sweet as they are together in this film. Keaton spent almost a month with the cow who plays Blue Eyes, going everywhere with her, feeding her and spending weeks with her. By the time they came to filming, the cow followed him without the slightest hesitation and never once seemed anything less than completely comfortable in his presence. Keaton (half) joked he never had a better leading lady than Blue Eyes – and his earnest, gentle and sincere playing of this friendship between man and beast gives Go West its heart.

Taking a gentle pop at DW Griffith again – Friendless and Blue Eyes both share names with leading characters from the director’s Intolerance – Keaton creates a film that many have called his one excursion into pathos but, for me, is all about creating character and story and having it service comedy. The laughs come faster for me in Go West than a farce like The Navigator because Keaton invests real warmth into this unlikely screen partnership. You invest in their story – these two outsiders, lonely and illtreated on the ranch, who find themselves as unlikely soul mates – and once you have that investment, you laugh along with their exploits.

Keaton also creates a variation on his usual character. Friendless is stoic but unlike other Keaton characters, he’s not bumbling or naïve, instead he seems to have accepted that he has no place in the world of men. Unlike other Keaton characters, he’s got an impressive ability to teach himself new skills rather than relying heavily on imitating others and reading instruction manuals. Friendless, slowly, picks up the skills of a ranch hand himself. Sure, he bungles his first attempts – his hilariously poor saddling of a horse (the saddle almost on the horses’ rump) being a case in point – but give him time and he’ll get there.

He’ll even win odd moments of respect. He gets two bulls back into the pen through skilful, unfazed, use of a red handkerchief (two ranch hands look on in grudging respect). He improvises an elastic string for his tiny pistol which works surprisingly well. He spots a cheat in a card-game and then skilfully disarms him (by placing his finger in the way of the trigger). In the film’s closing act – where a herd of bulls walk wildly around Los Angeles – he’s able to herd them back together with a great deal of skill, cunning and improvisation. He’s he’s undeniably good at the things he does – and gets better.

Go West has several great jokes, many of them initially based around Friendless’ place as an outsider. Selling his remaining goods to a pawnbroker in the films opening, he forgets to remove his shaving kit and mother’s picture from a desk: of course, the pawnbroker immediately charges him for taking the goods (making his money back in moments). On the ranch, Friendless inevitably times his arrival at the daily meals with everyone else finishing up and leaving the table, forcing Friendless to leave as well (he doesn’t eat for days on this ranch). His clumsy attempts at ranch life leads to several pratfalls of inevitable high-standard.

But it all starts to change as he forms a friendship with Blue Eyes. He’ll bend over backwards to help her. He’ll stay up all night with a gun to protect her from wolves. He’ll strap antlers to her head to help her ward off bulls. He’ll shave a brand (thank goodness he grabbed that shaving kit) into her back to save her from the fire. And he’ll raise what money he can to try and buy her and, when that fails, he’ll jump on a train to travel with her to save her.

It leads into the film’s action packed third act. It starts with a classic Keaton piece of business. Trying to earn the money to buy Blue Eyes, he buys into a rigged poker game. Calling the dealer on cheating, the ranch hand pulls a gun and orders Keaton “When you say that – SMILE”. Will cinema’s most famous stony-faced comic finally crack a grin? It’s a lovely in-joke – and Keaton’s two fingered mouth push grin the perfect response, as his ingeniously shrewd solution to prevent violence. Jumping on a train from here (this is another classic train sequence from a Keaton film) he dodges bullets from an attack from outlaws and ends up the only man on board with an army of cows.

The final sequence – a series of sight gags as cows invade shops, Turkish baths and street stalls in Los Angeles before Keaton dons a red-devil suit to lead them back into a holding pens in a perverse twist on Seven Chances – is sometimes overlong, but offers plenty of delights. But none match the sweetness and innocence of that friendship between man and cow. Keaton’s chemistry with Blue Eyes – and his understanding that the beauty of silence makes animals as legitimate characters in many ways as humans – shines out. It gives the film a real heart and tenderness that grounds all the jokes in something real, as well as providing the film with real stakes (because, after all, Blue Eyes is in danger of being turned into one).

Go West is often overlooked in the Keaton CV but, despite being a fraction overlong, it’s a warm, tender and sweet story packed with excellent gags. This isn’t manipulative pathos – instead this is Keaton using humanity to deliver a unique sort of pure romance. This is possibly one of the finest films about friendship ever made – and Blue Eyes stands with Balthasar as one of the greatest animal actors on screen.