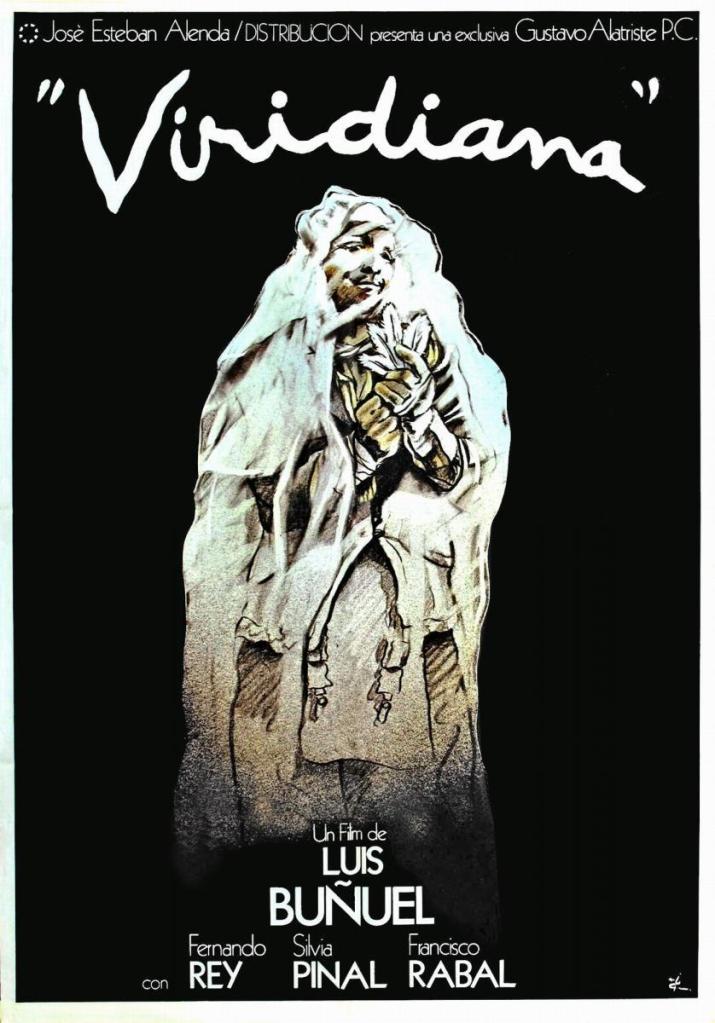

Luis Buñuel’s brilliant, multi-layered satire is a superb, darkly hilarious, masterful film

Director: Luis Buñuel

Cast: Silvia Pinal (Viridiana), Francisco Rabal (Jorge), Fernando Rey (Don Jaime), Margarita Lozano (Ramona), Victoria Zinny (Lucia), Teresita Rabal (Rita), José Calvo (Don Amalio), José Manuel Martín (“El Cojo”), Luis Heredia (“El Poca”), Joaquín Roa (Don Zequiel), Lola Gaos (Enedina), Juan García Tiendra (“El Leproso”)

In the 1960s, Luis Buñuel was invited back Spain after years of creative exile to spearhead a new wave of Spanish filmmaking. He produced a film that not only bit the right-wing hand that fed it, it snapped it clean off and chewed it up. Viridiana must have been the last thing the authorities had in mind. Gloriously exposing the guilt and vanity of the upper classes and charity, it was lambasted by the Catholic church for blasphemy and showed an organised world teetering on the brink of chaos, with the powerful either perverts or playboys, the poor singularly ungrateful for the paternalistic patronage they receive and our lead character a hopelessly naïve former nun. Not surprisingly it was instantly banned and Buñuel never made a film in Spain again.

Viridiana (Silvia Pinal) is our naïve nun, called to her uncle Don Jaime’s (Fernando Rey) home for one last visit before her confirmation. Don Jaime though has plans: Viridiana has an extraordinary resemblance to his late wife and Don Jaime intends to first get her to cos-play his wife and then marry him. Or failing that, to drug her and rape her. Guilt stops him from the rape – but doesn’t stop him from claiming he did it, a lie he instantly (fatally) regrets but which leads her to abandon her dreams of becoming a nun. In the aftermath, Viridiana and her cousin (Jaime’s bastard son) Jorge (Francisco Rabal) divide the estate, with Viridiana aiming to continue her religious ideals through excessively generous charity with quietly resentful local paupers, who she has a vision of turning into a religious commune. It does not turn out well.

Viridiana benches much of the surrealism of Buñuel’s most famous work, but it loses none of his acute social satire and ability to inject the absurd with sharp dark humour. It makes Viridiana a startingly complex work, brilliantly assembled by an artist where every frame has a different idea, all of which comes together into a darkly entertaining whole. Its not hard to see why the strictly Catholic Fascist Spain found the film so outrageous, with its mocking of religious imagery (from the crucifix that becomes a flick knife to the famous scene of the paupers forming a drunken, pose-perfect, tableau of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper), it’s acknowledgement of a host of fetishes and perversions among the upper-classes (orgies, feet, hinted necrophilia, incest) and the utter ineffectiveness of any system, no matter how charitable, to control the human spirit, with the poor frequently resentful under their veneer of deferential gratitude.

Viridiana splits neatly into two acts, both revolving around a complex relationship with guilt and how it guides our actions. Don Jaime (a superb performance of corrupted grandeur from Fernando Rey) is a lonely man, plagued with guilt and regret over his wife’s death, locking himself away in a time-locked country pile like a perverted Miss Havisham. In private he fetishistically admires her clothes (which he blasphemously keeps like holy relics) and admires his feet in her shoes. He’s fascinated by Viridiana’s resemblance to his late wife and fantasises that she might be persuaded to renounce the cloth to live as his wife.

With the convenience of his servant Ramana – an equally lonely, repressed soul tenderly played with a burgeoning sexual desire by Margarita Lozano – he guilt-trips Viridiana into dressing for one night in his wife’s bridal clothes, drugs her drink and takes her to bed. He even arranges the sleeping Viridiana into the exact pose his wife had when she was before him, adding hints of necrophilia to an already disgusting assault. Shame stops him from committing the deed and guilt then corrupts both of them. Don Jaime at his selfish lie, Viridiana at her indirect role in her uncle’s death and the forced abandonment of her vocation.

Inheriting her uncle’s home, alongside playboy cousin Jorge (Jaime’s bastard son, who he has barely met), Viridiana redirects this guilt into a commune for the poor and needy, where charity, work and faith sit side-by-side. Her efforts to essentially introduce a benign feudal church-system contrasts with Jorge’s modernising efforts, introducing electricity and other mod-cons. Buñuel demonstrates the discomfort of these two worlds with a beautifully assembled scene where Viridiana’s leads a group pray intercut with a series of shots of acts of manual labour (hammers smashing walls, cement splatted on bricks etc.), making he prayer meeting (which we know the attendees think is a pile of bunkum) seem even more outdated and ineffective.

Viridiana isn’t cruel about these characters though – it looks at them as real people, with faults and virtues, some good some bad. It’s also remarkably clear-eyed about charity. There is something performative about Viridiana’s efforts, as well as a clear sense it is as much for her (subconsciously – she’s too naïve for cynicism) as it is the welfare of the beneficiaries. Those beneficiaries are a brilliant series of pen portraits of people who take offered charity, but resent the paternalistic attitudes that come with it. The working classes are not passively grateful for religious charity – but they are smart enough to take a meal ticket. No wonder the church was furious: Viridiana ruthlessly exposes the lip-service the downtrodden give religious charity, while refusing to reshape their lives and views according to instruction.

The peasants remain earthy, irreverent and full of their own pleasures and prejudices. Despite Viridiana’s best efforts they abuse a (possibly leperous) beggar, tying a cowbell to him so they can hear him coming. When left alone in the grand house, they do what many of us might well do in their place: like teenagers resentful at their parents, they throw a drunken party and trash the place. Viridiana’s ‘dinner-party’ scene is Buñuel’s masterclass in riotous joy that slowly turns darker and more dangerous. Mockery leads to over-indulgence, anger and eventually violence. Viridiana will discover to her cost her attempts at kindness has done nothing to change their basic characters and it is as likely for someone to be downtrodden and deeply unpleasant as it is for them to be decent.

Charity in Viridiana doesn’t really change the world. It can improve lives, but not the system. And using it to shape people into what you want them to be is doomed to failure. The peasants are (mostly) not bad people, they just don’t feel want to reshape themselves into pious substitute nuns for Viridiana as a pay-off for room and board. Jorge is distressed to see a working dog tied to a cart and forced to run alongside it. He impulsively buys the dog – which to its original owner is not a pet but a working animal that must own its keep. Jorge clearly feels good about saving this dog: but seconds after he walks away with it, Buñuel pans across to another identical dog running behind a cart. Who was this charity for? The dog or for Jorge? The peasants of Viridiana? And did this one act change anything? And for some charity is entirely self serving: Viridiana visits Don Jaime solely out of thanks for his charity in paying for her time in the convent – surely an act only carried out for Jamie’s own perverted reasons.

None of this is what the Church or Spanish state wanted to hear. A downtrodden class that isn’t grateful to its leaders for lifting them up, but resents them for their patronising strictures. Lords of the manor, one of whom is a lonely pervert, the second a libidinous playboy who sleeps with multiple women. A deeply religious woman, who is completely naïve and fails utterly. And an ending – an ending Buñuel was ordered to change from the script and in doing so made even more suggestive and blasphemous – that implies the household will settle into a sexual menage.

It’s brilliantly, pointedly not what he was asked for – and stunning condemnation of the flaws in an entire system, caught in a brilliant parable. It’s superbly directed by Buñuel, by now a master of camerawork and editing with a beautifully judged performance by Silvia Pinal who makes Viridiana someone we deeply admire even as every decision she makes seems doomed for disaster. It’s a fiercely challenging, involving and complex work and infinitely rewarding for reviewing and patient consideration – no wonder Spanish critics later named it the greatest Spanish film ever made.