|

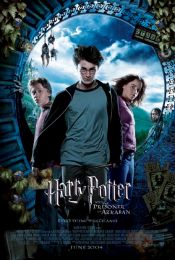

Clive Owen and Claire-Hope Ashitey could be the last hope for mankind in the masterful Children of Men |

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Cast: Clive Owen (Theo Faron), Julianne Moore (Julian Taylor), Claire-Hope Ashitey (Kee), Michael Caine (Jasper Palmer), Chiwetel Ejiofor (Luke), Charlie Hunnam (Patric), Pam Ferris (Miriam), Peter Mullan (Syd), Danny Huston (Nigel)

Children of Men was overlooked on release. But the more it ages, the more it clearly hasn’t aged it at all. Criminally ignored at the major awards, this might well be the finest film of 2006 and certainly one of the best movies of the noughties. Rich in thought-provoking content and cinematic skill, this is truly great-film-making from Alfonso Cuarón. Dark, grim, edgy but also laced with hope, faith and kindness, Children of Men grows in statue with each viewing, rewarding you more and more.

It’s 2027 and the world has gone to hell. Mysteriously mankind became infertile 18 years ago, and faced with the despair that the extinction of the human race is inevitable, society has collapsed. Cities lie in ruins and war has torn countries apart: Britain “stands alone”, one of the few with a functioning government – even though that government is a totalitarian, nationalist police state. Aggressive campaigns are waged against refugees from around the world, who are herded into hellish concentration camps. In this chaos, Theo (Clive Owen) is a disaffected civil rights activist, now plodding through a dead-end job and smoking weed with his friend, ex-newspaper cartoonist Jasper (Michael Owen). All this changes when he is entrusted by his activist/’terrorist’ estranged wife Julian (Julianne Moore) to protect Kee (Claire-Hope Ashitey) who carries inside her something that could change the whole of humanity: an unborn child.

Today Children of Men seems alarmingly prescient. In a world of migrant crises, Brexit, Trump and coronavirus (the film even refers to a flu pandemic of 2008!) the vision of the future it presents seems only a few degrees away from our reality. Rather than a hellish view, it seems more and more like something that could happen. Everything is worn out and grubby. Streets are lined with rubbish, buildings coated with graffiti. Televisions and advertising screens alternate between demands to report immigrants with promotions for “Quietus”, a suicide pill. Fences, armed police, barbed wire and crowds of filthy, terrified and brutalised people are common. Humanity has given-up: there is no hope in the world.

It’s that collapse of any sense of hope and optimism that has driven this collapse of society in Cuarón’s vision. In a world where the extinction of mankind is inevitable, what’s the point contributing to society or worrying about your legacy or the future? Why preserve anything when no-one will be around to see it in a hundred years? By such fragile threads, does society hold itself together. The crushing depression of knowing you live in the final days of humanity is everywhere. There is not a single person alive in their teens: a fact hammered home by the characters visiting a deserted and derelict school. Everyone has lost any sense of purpose, with life a grim daily grind.

Perhaps that’s also why physically the world hasn’t changed much. Unlike most “future set” dramas, this view of 2027 could be 2006, just dirtier and with a few more electronic screens (in fact this has helped hugely in not dating the film). It’s like all life has stagnated. And liberals like Theo have turned into apathetic drunks, drifting blithely through life not bothering to engage or change anything about the shit show all around them

All this makes the film sound impossibly grim – and Cuarón is superb in building this world (including the genius stroke of never explaining, even in the smallest detail, what has caused this pandemic of infertility – the film is refreshingly free of any clumsy scene setting) – but it works because it’s a film laced with hope and a belief in the fundamental goodness of people. The story has overtones of a religious fable: Theo and Kee as a sort of Joseph and Mary travelling to protect an unborn child whose birth could save the world. Specially composed choral music, rife with religious overtones, underplays key moments and scenes subtly leaning into this spiritual journey.

And the goodness that people find in themselves is inspiring. Theo, brilliantly played by Clive Owen who has just the right dissolute cynicism hiding crusading courage, may have given up but actually he’s a deeply empathetic and caring man. Animals instinctively love him. He’s a natural protector, who shows concern in all sorts of ways for people him, who puts himself at risk to protect people and refuses to ever accept defeat. But he’s a million miles away from a super-man, getting increasingly dishevelled, bashed and brutalised, while his struggles with footwear (he carries out action sequences wearing just socks, then flip-flops and finally barefoot) is both a neat little gag and also a sign of how vulnerable he is in this dangerous world.

Cuarón’s film builds brilliantly on his empathy to carefully and beautifully build the growing understanding and trust between Theo and Kee (equally well played by Claire-Hope Ashitey). Again, it stems first from his protectiveness (Theo also works hard to protect people around him from disturbing sights, twice urging Kee not to look back and that whoever has been left behind is fine), but also from her instinctive trust in him as a good man and above the only one who seems to have her interests at heart (everyone else is concerned only with what Kee can symbolise – Ejiofor’s vigilante Luke can’t even get the sex of the baby right). Kee is vulnerable, but strong and determined, someone trying to carry the burden of being the hope of mankind.

She’s also brilliantly a member of the very migrant community that the government is trying to destroy. Cuarón’s film wants us all to remember that we are all the same deep down, that what happens to one affects us all. The horrors of what the British government are doing in the war-torn slums of migrant prisons (all of Bexhill has become a lawless hell hole, where executions and riots are daily occurrences) reek of everything from Auschwitz to Guantanamo. But amongst these migrants come the only strangers who seek to help Theo and Kee out of simple goodness and humanity. Strangers put themselves at huge risk, and in many cases sacrifice their lives, to help them. It makes a stark contrast with the revolutionaries who claim to fight for the migrants (but show no compunction in shooting them when needed), but really are only interested in their own selfish battles with no understanding of the bigger picture.

This bigger picture is very much like the thematic richness of the film that was missed on its released. It’s almost a victim of its own technical brilliance, which attracted much more attention at the time. Cuarón constructs several sequences to appear as single-takes, and the stunning camera work really helps establish this grimy, brutal world. It’s a wonderfully immersive film, a technical marvel. Every single part of the photography and design is pitch-perfect, and the key sequences are stomach-churningly tense, inspired by everything from The Battle of Algiers to A Clockwork Orange.

But the film works because it is underpinned by faith and trust in the human spirit. Mankind is being challenged like never before, but Cuarón shows us that the human spirit can survive. That simple acts of kindness can still happen. That there is a chance of hope. The final conclusion of the film is both sad but also upliftingly hopeful. Cuarón’s direction is just-about perfect, as are the performers (not just Owen and Ashitey but also an almost unrecognisible Caine as an ageing Hippie). With its acute and brilliant analysis of humanity – both in its grimness and capacity for goodness and selflessness – and with its prescient look at how easily our world could collapse, Children of Men is vibrant, brilliant, essential film-making.