|

Tippi Hedron has a bad day at the birdcage in The Birds |

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Cast: Tippi Hedron (Melanie Daniels), Rod Taylor (Mitch Brenner), Jessica Tandy (Lydia Brenner), Suzanne Pleshette (Annie Hayworth), Veronica Cartwright (Cathy Brenner), Charles McGraw (Sebastian Sholes), Lonny Chapman (Deke Carter), Joe Mantell (Cynical Businessman)

Alfred Hitchcock is often seen as the master of technique, the doyen of suspense, the master of the shock twist. Perhaps it was his love of this sort of material that led him to this radical reworking of Daphne du Maurier’s short story The Birds. After all Hitch had already directed the greatest ever du Maurier adaptation (Rebecca), so working with du Maurier was hardly new and turning this English suspense story into a sort of post-apocalyptic, tension-filled plot-boiler was right up his street. The Birds is a master-class in the director’s craft, and a curiously empty experience with barely a human heart in sight.

Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedron), a slightly spoiled heiress, arrives in a small coastal town in California in order to play a practical trick on lawyer Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor). Deciding to stay the night, she quickly realises that she has chosen the wrong weekend to get away as, while sparks grow between her and Rod, they also grow between humanity and the birds, as our feathered friends (enemies?) begin a series of escalating attacks on the population of the town that eventually lead to multiple deaths and destruction.

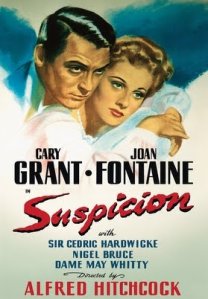

Hitchcock’s film is as masterclass in the slow-burn, deliberately the slowest film the director perhaps ever made. Hitchcock prided himself on his films in suspense being the awaiting of an event to happen. The bomb you know will go off on the bus. The plane circling Cary Grant that seems ripe to attack. The Birds takes this to the nth degree. The film’s very title all but tells you that the birds are going to attack, so Hitchcock takes it nice and slow, letting scenes play out with a breezy lack of pace, almost like a low-rent romantic comedy. But somehow this long unwinding of not a lot happening works well, because every scene somehow becomes a corkscrew as tension as every single bird in shot becomes suspicious.

This atmosphere is increased by the wide open locations and remote locale the film is set in, with these all-American small town sites seeming to stretch on forever around the characters only serving to stress their isolation and vulnerability in the middle of all this deadly nature. Hitchcock also carefully stripped out all musical score from the film, instead providing a sound track of natural noise complemented by slightly exaggerated bird noise (created by use of a Trautonium, supervised by master composer Bernard Herrmann). The often makes the film eerily and unsettlingly quiet, with the soundtrack only punctured by the frequently (perhaps deliberately) mundane dialogue. Suddenly with this brilliant combination game, the entire film becomes a tense waiting game for the unleashing of avian attacks, every frame a tense waiting for the bang you all know is coming. It’s Hitchcock using every aspect of his reputation, and the film’s promise of violence, to create an overwhelming effect that is deeply unsettling no matter how many times you see the movie.

Hitchcock also gives a slow build to the bird violence. Events escalate quickly, from the unsettling gathering of the birds in several places (most notably along telephone lines and outside a school playground) to subtle messages about chicken’s refusing food, to first Melanie and the other characters colliding with or being bitten by birds. It all builds to a grim reveal of a local farmer who has been attacked over-night, with Rod’s mother stumbling across the mutilated old man, Hitchcock’s camera delightedly cross cutting onto the man’s pecked out eyes. It’s the most grotesque shot of the film – and coming before we’ve seen our first mass bird attack, leaves us in no doubt as to the danger of these animals.

And when those bird effects come they have a real unsettling violence to them. In a blur of both real birds and super-imposed images (I will admit that the special effects of this film do now look a little dated, with the mixture of real, model and photo trickery birds rather jarring) the birds fly with an almost unimaginable aggression at the human beings. Flocks descend, pecking, biting and clawing, leaving human bodies maimed, blinded and bloodied. Crowds of school children are attacked while fleeing their school. A gas attendant is brutally set upon leading to a firey conflagration. Passers-by and those unable to get refuge are beaten to the ground under a flood of winged assailants.

The film changes tack in its final sequence into a tense series of sieges as Melanie, Rod and his family hole up in Rod’s house by the lake, barricading doors and windows as the birds peck relentlessly at doors and windows, slowly forcing their way in. Rooms that fall to the birds become whirlpools of deadly flying creatures, a tornado of wings and pecks that few can stand against. Hitchcock’s camera cuts rapidly from the flood of birds, to ever increasing pecks at hands and arms, to hands thrown up to protect eyes – a brilliant call back to the eye horror shown earlier in the film that immediately inspires. The birds attack in unpredictable waves, their attacks dying down at moments as the sit calmly and placidly only to expectantly burst back into violence.

It’s just a shame that Hitchcock’s film is so enamoured with its undeniable technique that it neglects to feature any heart or soul at all. The characters are a stock collection of forgettable tropes, most played by forgettable actors, or mute ciphers. The film almost deliberately throws together a truly trivial collection of stories and character motivations to pepper the centre (perhaps this bland self-interest is what pisses the birds off so much) of the film, that frankly are not that interesting. Rod Taylor is a solid but uninspiring performer, Jessica Tandy is saddled with a truly pathetically weak role. So many of the other characters such little impact that they barely warrant names. Rarely in Hitchcock films have the human characters felt so much like devices, square pegs in square holes, totally subservient to the Master’s whims. Put frankly, for all the tension of when the birds will turn, you’ll care very little for any of their victims.

A lot of focus on the film has been on Tippi Hedron, in particular her accusations of ill-treatment (routed in frustrated sexual obsession) from Hitchcock. These stories – and Hitchcock’s subsequent description of her as little more than an attractive prop (a feeling he tended to have for lots of actors) – have drawn attention away from the fact that she is actually very effective in The Birds, and that her brightness and intelligence makes her the only person who feels real in the whole film. It makes it all the more sad that the final sequence renders her into a mute, shell-shocked victim – but Hedron’s promise (never fulfilled due to Hitchcock’s sabotage of her career) is clear here.

Hitchcock’s film finally ends on a truly nihilistic, Armageddon tinged ending that speaks volumes for the post-apocalyptic nuclear anxiety prevalent in the West in the 1960s. The birds rest, triumphant, over the chilling silence of the world as what remains of our heroes beat a retreat. It’s a chilling flourish in a film that is a stylist’s triumph but lacks any real heart. It’s a film that haunts the memory but it doesn’t win the heart. If Hitchcock really did hate actors and most people, this film makes a good case for arguing that’s a pretty honest insight.