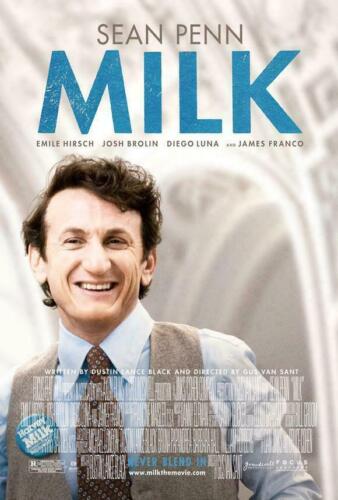

A political pioneer is lovingly paid tribute to in van Sant’s heartfelt biopic

Director: Gus van Sant

Cast: Sean Penn (Harvey Milk), Emile Hirsch (Cleve Jones), Josh Brolin (Dan White), Diego Luna (Jack Lira), James Franco (Scott Smith), Alison Pill (Anne Kronenberg), Victor Garber (Major George Mascone), Denis O’Hare (State Senator John Briggs), Joseph Cross (Dick Pabich), Stephen Spinella (Rick Stokes), Lucas Grabeel (Danny Nicoletta)

Harvey Milk was the first openly gay man elected to public office in the United States. Milk is a passionate, accessible and lovingly crafted biopic from Gus van Sant, which aims to restore this crucial figure back to the heart of public consciousness. van Sant covers a lot, but he crafts a film that hums with respect and a great deal of life. It also gains a huge amount from Sean Penn’s extraordinary and compassionate Oscar-winning performance, which embodies the spirit of this political pioneer.

Milk, in many ways, takes a traditional biopic approach, attempting to capture all the major events of Milk’s life in just over two hours. We follow Milk (Sean Penn) from closeted office worker, starting a relationship with Scott Smith (James Franco) to San Francisco and becoming part of a vibrant gay community – although one still facing an onslaught of discrimination and persecution from the authorities. Milk determines to change things, eventually elected as City Supervisor in 1977. From there he fights against the anti-gay Proposition 6 and pushes for change, until his murder by fellow City Supervisor Dan White (Josh Brolin) in November 1978.

Milk makes a strong statement about the dangers faced by the gay community in this period of American history. It opens with a montage of newsreel footage showing the impact of raids and the reaction to Milk’s murder. It explores in detail the vicious backlash against gay rights across America, with Florida among several states passing legislation to repeal rights. There is a creeping sense of danger throughout, from Milk walking down a dark street looking over his shoulder, to the everyday prejudice characters encounter on the streets. Above all perhaps, it strongly demonstrates the powerful sense of shame people were driven into about their sexuality, most powerfully in a young man who cold-calls Milk begging for help. Milk fascinatingly explores the tensions within the gay community and its representatives – split between radicals, like Milk and his friends, and the more traditional elite worried someone “too gay” will alienate people.

It’s a beautifully shot, loving recreation of 1970s San Francisco, fast-paced, insightful and informative. As Harvey Milk, Sean Penn gives an extraordinary, transformative performance. Penn’s careful study has beautifully reproduced Milk’s mannerisms and vocal tics, but above all he has captured a sense of the man’s soul. Penn presents Milk as fiery but caring, loving but sometimes selfish, passionate but reasoned, both an activist and a politician. He’s a man determined to make life better, so young men don’t feel the shame he felt growing up – not a hero or a superman, just someone who feels he can (and should) make a difference. Penn’s energetic performance mixes gentleness with a justified vein of anger at injustice.

And he has a lot to be angry about. The film’s finest sequence is Milk’s duel with Senator John Briggs (waspishly played by Denis O’Hare) over Proposition 6. van Sant skilfully re-constructs the debate, but also carefully elucidates the high stakes and the impact its passing would have had. van Sant’s film is frequently strong not only at reconstruction but also in using drama to inform and, above all, to bring to life the sense of hope people had that the struggle could lead to change.

The film grounds Milk firmly within his relationships and friendships, while exploring clearly the issues that motivated him so strongly. To do this, the film shies away from Milk’s polyamorous relationships, grounding him in a series of long-term relationships, some functional and some not. It presents Scott Smith (sensitively played by James Franco) as Milk’s lost “soul-mate” (the couple split over Milk’s all-consuming focus on campaigning) – perhaps van Sant’s attempt to keep the film as accessible as possible by introducing a more traditional element. Smith is contrasted with Jack Lira (Diego Luna), a sulky and immature man equally alienated by Milk’s focus.

Those personal relationships are extended to explore the tensions and fractured friendship between Milk and his eventual murderer Dan White. You’d expect the film to recraft White as a homophobic killer. Instead, it acknowledges White’s crime was largely motivated by factors other than gay rights, primarily his mental collapse and his sense of aggrievement over a workplace dispute. Sensitively played by Josh Brolin, White is presented as a man’s man suffering from a deep sense of inadequacy and insecurity (the film openly suggests he may have been closeted himself). Milk’s mistake is misunderstanding the depths of this man’s insecurities and never imagining the lengths they might drive him to. Brolin is very good as this troubled, if finally unsympathetic, man.

Milk of course fully anticipated being murdered – it was just he expected a homophobic slaying at a rally, rather than an office shooting by an aggrieved co-worker. One of the clumsier devices used in the film is its framing device of Milk recording his will a few days before his unexpected murder, a device that seems to exist solely to allow Penn to pop up and explain things more fully at points the film can’t find another way to expand. But again, it might be another deliberate attempt by van Sant and writer Dustin Lance Black to make a film as accessible as possible, by falling back on traditional biopic devices (including its semi-cradle-to-grave structure), just as he aims to shoot the film in a vibrant but linear and visually clear style, avoiding overt flash and snappy camera and editing tricks.

Perhaps that’s because the film generally knows it doesn’t need to overplay its hand to capture emotion (when it does, it’s less effective: you could argue its slow-mo murder of Milk to the sound of Tosca is far less affecting than the look of shock and horror that crosses Penn’s face a moment earlier when he realises what is about to happen – a cut to black might have worked more effectively here). Actual footage of the candlelit vigil after his murder, mixed with reconstruction, is simple but carries real impact. Throughout the film, real-life stories pop-up time and again of prejudice and pain, which move with their honesty. Above all, it becomes a beautiful tribute to a passionate, brave and extraordinary man who left the world a better place than he found it.