Bergman’s gorgeous final film, a sublime family saga, that leaves you thinking for days

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Cast: Bertil Guve (Alexander Ekdahl), Pernilla Allwin (Fanny Ekdahl), Ewa Fröling (Emilie Ekdahl), Jan Malmsjö (Bishop Edvard Vergérus), Gunn Wållgren (Helena Ekdahl), Erland Josephson (Isak Jacobi), Jarl Kulle (Gustav Adolf Ekdahl), Allan Edwall (Oscar Ekdahl), Pernilla August (Maj), Mona Malm (Alma Ekdahl), Börje Ahlstedt (Carl Ekdahl), Christina Schollin (Lydia Ekdahl), Harriet Andersson (Justina), Stina Ekblad (Ismael Retzinsky), Mats Bergman (Aron Retzinsky), Gunnar Björnstrand (Filip Landahl)

After many years (and masterpieces) Bergman wanted to move on from film: but before he went, there was time for one more magnum opus, a sprawling family saga that would throw a host of his interests (death, family, sexual openness, God, theatre, infidelity, the unknowable) onto one grand, sprawling canvas. Fanny and Alexander would be a truly personal film, featuring a young protagonist with more than a passing resemblance to Bergman himself. Despite this it’s an irony Bergman might like that the finest version of this film we have is actually a five-hour recut for television (the limits of run-time from distributors being one of many things Bergman was tired of). That version is a beautiful, life-affirming, gorgeous piece of film-making, an extraordinarily humane story tinged with the supernatural told on a luscious, Visconti-like scale. It’s a fitting sign-off from a master.

In 1907, the wealthy Ekdahl family live in a luxurious apartment block, their rooms filled with the rich detail of their love of art and culture. Ten-year-old Alexander’s (Bertil Guve) father Oscar (Allan Edwall) and mother Emilie (Ewa Fröling) run the Ekhdal theatre, where his wealthy grandmother Helena (Gunn Wållgren) once performed. After a fabulous Christmas celebration, Oscar dies after a stroke while rehearsing the role of the Ghost in Hamlet. After a period of mourning, Emilie remarries to the older Bishop Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjö), who turns out to be a domestic tyrant, obsessed with the letter of religious and family law. Will Alexander, his younger sister Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and their mother escape from Vergérus’ controlling clutches?

What really strikes you first and foremost about Fanny and Alexander is its gorgeous warmth – hardly the first quality you traditionally associate with Bergman. It opens with a prolonged (over an hour) Christmas celebration, with the family and their servants eating, laughing, telling stories and dancing through their gorgeously furnished apartment. It should feel indulgent (and I suppose it is), but this warm reconstruction of an at-times-flawed, but fundamentally loving and vibrant family is actually deeply moving and heart-warming.

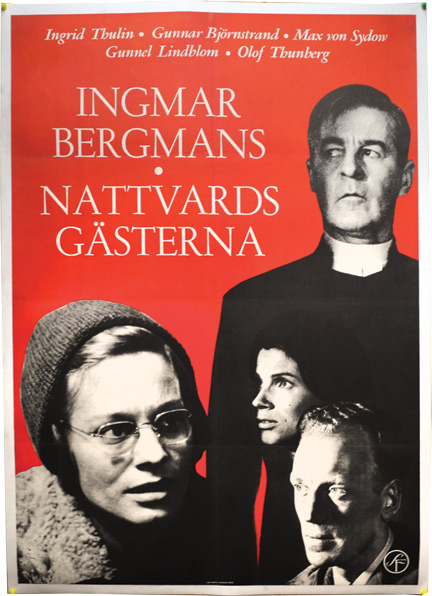

The Ekdahls have a bohemian freedom, with their love of theatre and art (only Uncle Carl, a manic depressive businessman, feels slightly out-of-place and even he takes the children to one-side during the festivities to entertain them by blowing out candles with his farts). Their house is charmingly egalitarian, with the servants treated as part of the family, loyalty they return. The theatre troupe (led by Bergman regular Gunnar Björnstrand in his final, small, role) – are equally part of this extended family, the theatre a second magical home where the children take small roles in various productions and delight in the stagecraft and costumes behind-the-scenes.

Fitting a Bergman family (and the Ekdahl’s share some elements with parts of Bergman’s family) they are extremely forward-looking in their morality. Uncle Gustav Adolf (played with bombastic, gentle charm by Jarl Kulle) is a notorious ladies man, but goes about it with such innocence and near-childish openness his patient wife Alma (Mona Malm) indulges him because in all other respects he’s a loving husband and father, and his overall fidelity to her is never in doubt. Alma restricts herself to a single slap of his new lover, maid Maj, but otherwise treats her like a sister. Pernilla August is hugely endearing as this caring young woman, swiftly absorbed into the wider Ekdahl family who value her care for others. The Ekdahl’s have no time for conventional morality, led from the front by matriarch Helena (Gunn Wållgren is fantastic as this wordly-wise, ideal grandmother figure) who has lived a life of sexual openness with her husband and values people not societal conventions.

Oscar, their father (wonderfully played by Allan Edwall as a bashfully mediocre actor and a quietly shy but warm man) takes his role as the leader of this company very seriously, but with a light touch (modestly bemoaning his lack of statue compared to his father). Bergman uses a myriad of small moments to make this father an ideal parent, not least a late-night fantastical story he improvises for the children, spun around their nursery room chair, one of the most tender moments of parent-child bonding in the movies. (This despite hints that Oscar, who has allowed the younger, more sensual Emilie to conduct her own affairs, might not be their true father).

The stunning production and costume design (which won Oscars for Anna Asp and Marik Vos-Lundh) are essential for creating this immersive, rich and vibrant life: one which will be exploded in Dickensian tragedy by the death of Oscar and the arrival of the Murdstone-like Edvard Vergérus (played with chilling, smug hypocrisy by Jan Malmsjö under a fake smile) who is everything the Ekdahls are not. Where they are warm and egalitarian, he is cool and elitist, he is a prude with no regard for art and his home is in bleached-out puritan stone, devoid of personal touches – it literally looks like a different world to that we’ve spent the first few hours in, full of untrustworthy people (like Vergérus’ maid played by a wonderfully two-faced Harriet Andersson).

Vergérus is all about control, something we suspect from the start with his aggressively tender manhandling of Alexander, his hand slamming into the back of his neck. He worms his way into the affections of Emilie – a woman who, with her earth-shattering wails over the body of Oscar, is clearly vulnerable in her raw grief (Ewa Fröling is extraordinary as this gentle figure, prone to appalling judgement and unexpected strength of character) – and then sets out their marriage terms with controlling agendas, not least that in arriving in his house, she and her children must shed every inch of their previous life, from personal connections to the knick-knacks they have grown to love. He’s a poor advert for a God Alexander is already cursing for taking his father (his attic, filled with crumbling religious symbols, feels of a part of Bergman’s world where God is at best a passive observer, at worst a near malicious presence).

Bergman makes clear Vergérus is a man who genuinely believes he is doing the best for his family and that the moral lessons he hands out, at the end of a cane, to Alexander are essential. A weak man who mistakes bullying for strength. In many ways the fact he is not vindictive just weak and convinced of his own moral certainty (re-enforced by his fawning family, who treat him like a sort of prophet). Sure, he’s capable of anger, anti-Semitic slurs and little acts of cruelty, but Malmsjö shows him as a man who is trying, in his own wrong-headed way, to win the love of his adopted wife and children and can’t understand why he is not met with gratitude and love.

Perhaps it’s this sudden dropping into a cold world (one not dissimilar from Bergman’s own troubled relationship with his priest father – in fact you leave Fanny and Alexander wondering if Bergman hated his own father as much as Alexander who literally prays for his death) that so sparks Alexander’s own links to a mystic world around him. There is a rich vein of something other throughout Fanny and Alexander, from the statues Alexander watches move in the opening sequence (not to mention the haunting spectre of Death he witnesses in the same moment), to Oscar constantly appearing to Alexander like Hamlet’s Ghost. Is this haunting Alexander’s guilt at this failure to face his dying father on his deathbed, or a link to a world beyond our understanding?

After all Oscar’s Ghost greets Helena at one point, the two entering into a loving conversation. And he’s not the only supernatural touch around Fanny and Alexander. Family friend (and Helena’s lover) the Jew Isak (a rich performance by Bergman regular Erland Josephson) lives in a house full of mystic puppets that might be able to breath and walk. Isak perhaps uses magic to help smuggle the children out of Vergérus’ house (making them appear in two places at once), while his androgenous son Ismael (played by a woman, Stina Ekbad) is implied to having the spiritual power to channel Alexander’s hatred of Vergérus into actual supernatural revenge in the real world (another classic literary touch, that plays on spirituality and the Mad Woman in the Attic in Jane Eyre).

Fanny and Alexander is an extraordinary film, I feel I have only begun to scratch its surface here. It’s both a Dickensian family fable and a semi-benevolent Ghost story. It’s a family saga and a careful look at a particular time and place. It’s funny and moving. It really feels like one final mighty effort from a master.