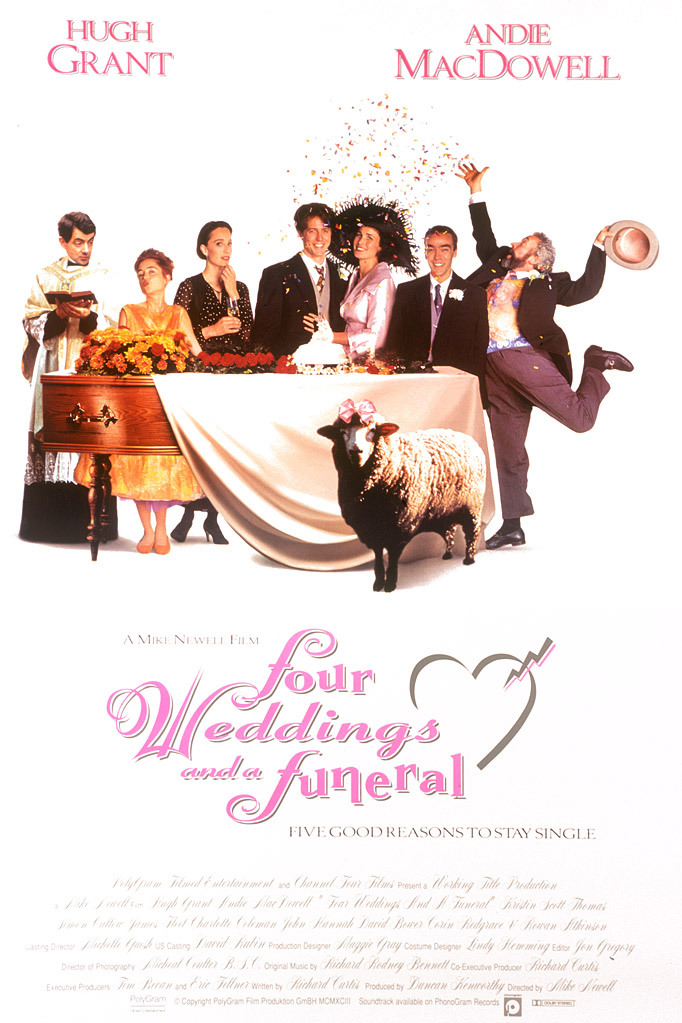

The phenomenon of the 90s, this charming comedy still (rightly) lies in many people’s soft spot

Director: Mike Newell

Cast: Hugh Grant (Charles), Andie MacDowell (Carrie), Simon Callow (Gareth), Anna Chancellor (Henrietta), Charlotte Coleman (Scarlett), James Fleet (Tom), John Hannah (Matthew), Kristin Scott-Thomas (Fiona), David Bower (David), Rowan Atkinson (Father Gerald), David Haig (Bernard), Sophie Thompson (Lydia), Corin Redgrave (Hamish Banks), Simon Kunz (John), Rupert Vansittart (George)

It’s 1994 and love really is all around. It certainly felt like it in the UK, as Four Weddings and a Funeral went from small Brit rom-com to national phenomenon. It was number one at the box office for ten weeks and Wet Wet Wet’s Love is All Around felt like it was number one for the whole year. The film was a huge international hit, the sort of once-in-a-lifetime movie for everyone involved, culminating in an Oscar nomination for Best Picture. For anyone who went to the movies in the 90s, it feels like an old, familiar friend. And, leaving aside the inevitable backlash, it’s still witty, charming and fun today.

Based on writer Richard Curtis’ experience of attending a never-ending parade of weddings one year (we’ve all been there), we follow Charles (Hugh Grant) through a series of disastrously different weddings (and, of course, one moving funeral) while he tries to deal with the fact he’s fallen in love with American Carrie (Andie MacDowell) – and one of the weddings he attends is hers. Around him float a phalanx of loyal friends: gregarious Gareth (Simon Callow) and his loyal, utterly reliable partner Matthew (John Hannah), dimly posh Tom (James Fleet) and his arch sister Fiona (Kristin Scott-Thomas) and zany Scarlett (Charlotte Coleman). But, when the time comes for Charles to head down the aisle, who will he find waiting for him at the end?

Four Weddings works because it’s blessed with a series of talents at the peak of their powers. Richard Curtis has never written a film script that balances so perfectly excellent one-liners, sharply sketched, engaging characters and a perfect mix of pathos and belly-laughs. Mike Newell balances the comedy with just the right touch of drama, never allowing events to tip into sitcom territory. The cast are all pretty much selected perfectly. And above all, it turned out Hugh Grant was placed on earth to play the lead roles in Curtis comedies.

Before Four Weddings, Hugh Grant was almost completely unknown: a Merchant Ivory supporting player at best. After it, he would be almost indistinguishable in the public’s eye from Charles (he’d effectively play the same role three times again for Curtis). What Grant does in this film is simply phenomenal. Curtis’ dialogue and rhythm fits his style like a glove: not since Rowan Atkinson (who delivers a Peter Sellars like performance as a nervous and shy vicar at the other end of the comic spectrum from Grant’s mix of comedy and pained earnestness) had an actor clicked so much with Curtis. There is, perhaps, no skill harder than light comedy, but Grant is a master at it.

He turns socially awkward comedy into a thing of beauty (trapped at a table with a series of ex-girlfriends, he lets the smallest inflections telegraph his desire for the earth to swallow him). He has the subtlety to not overplay pratfalls or physical gags (look at the minimalist simplicity which he plays being trapped, hiding, in a cupboard while a recently married couple have noisy sex in the same room, his face a mix of pained embarrassment and longing for escape). Grant captures better than almost any actor alive a peculiar, self-deprecating British sense of humour, the quiet rabbit-in-the-headlight horror of saying the wrong thing. He even makes you love Charles (who, in many ways, is a self-obsessed git) because Grant is so effortlessly likeable, emitting rays of little-boy lost charm.

It also works because the film crams into it a hinterland of friendship and warmth. The chemistry between the company is pretty much spot-on – you never for one moment doubt these people are lifelong friends, despite the fact we learn nearly nothing about any of them over the course of the film (even Charles – what other film would not even tell us his job?). Each of the actors seizes their role with relish. Simon Callow got to explode with red-faced bonhomie and shaggy-faced camp in a way you suspect he had been dying to do his whole career. Kristin Scott-Thomas’ arch dryness and icy posture was leavened with just the right touch of romantic yearning and wit.

In fact, the whole cast were so perfectly cast they almost became destined to spend their whole lives struggling to break out of the moulds Four Weddings placed them in. James Fleet was so skilled at nice-but-dim sweeties like Tom, he had to grow a huge beard to get serious roles. John Hannah (extremely good, with the films much touching WH Auden inspired moment) took on playing a posh twit in The Mummy. Anna Chancellor was so born to play the strangely needy ‘Duckface’, Charles’ ex-girlfriend she jokes the first line of her obituary will be “Duckface dies”. Callow and Scott-Thomas would play versions of these roles several times over – and even being arrested for picking up a sex worker wouldn’t break the public perception of Grant being Charles.

Which is all a round-about way of saying everything works here, the magic alchemy of everyone being in the right place at the right time, and every single risk paying off. You can be slightly churlish and say Andie MacDowell lacks some of the charisma and comic skill the role of Carrie needs (it’s a Meg Ryan role), but her innocent Southern exterior is needed to make the scene of her recounting her serial shagging to Charles over a restaurant table land with as much comic force as it does.

That’s one of many comic set-pieces that just plain work. From the “fuck!”-filled opening montage, which sees Charles hare, late, to a wedding where he is the best man, via the film’s many social faux pas (“She is now my wife” has never been funnier), Atkinson’s malapropism-stuffed wedding service to the film’s final comic denouement at Charles’ wedding, it’s packed with laugh-out-loud moments. But, because the characters are so well-drawn, with just the right amount of reality, we also care as well. The funeral carries real emotional impact – not least due to Hannah’s beautiful delivery of the eulogy (and let’s not forget, few other mainstream movies were as open to homosexuality at the time as this one). And every character has moments of depth: even dim Tom has flashes of real emotional insight.

You can mock it in retrospect for moments like “is it raining, I hadn’t noticed” – but films like this don’t stumble into becoming cultural phenomena. They get there because, for one glorious moment, everything comes together the way it was meant to be. A great script got just the right approach, from a series of actors perfectly cast and marshalled by a director towards warm, genuine comedy. That’s why people continue to watch – and quote it – thirty years later and it still feels like love is all around it.