Low-key, beautifully made short-story anthology, crammed with wonderfully little touches

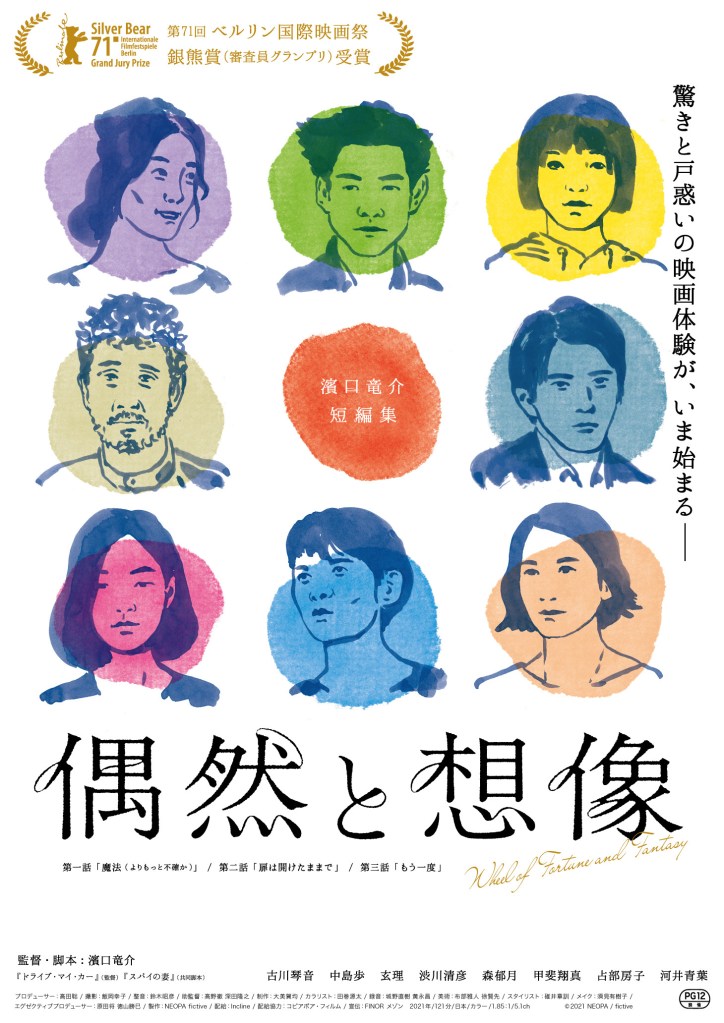

Director: Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Cast: Kotone Furukawa (Meiko), Ayumu Nakajima (Kazuaki Kubota), Hyunri (Tsugumi Konno), Kiyohiko Shibukawa (Segawa), Katsuki Mori (Nao), Shouma Kai (Sasaki), Fusako Urabe (Moka Natsuko), Aoba Kawai (Nana Aya)

Hamaguchi’s Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy feels deceptively simple. But it’s the Japanese auteur combining an Ozu-inspired sensibility with the narrative flair of Chekhov. In its three acts, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy presents three short stories, each chamber pieces, each revolving around intimate, intense and life-changing conversations between two people. Hamaguchi demonstrates how lives can rotate on their axis in split seconds, with conversations shifting for one or both participants with no warning, generating unexpected, emotionally surprising results.

‘Magic’, the first story, revolves around model Meiko (Kotone Furukawa) and best friend Tsugami (Hyunri). During a long cab journey, Tsugami tells Meiko all about her new romance – only for Meiko to realise, part way through, she is talking about Meiko’s ex-boyfriend Kazuaki (Ayumu Nakajima) with whom Meiko may still love. ‘Door Wide Open’ sees distinguished professor and author Segawa (Kiyohiko Shibukawa) become the unsuspecting target of a honey trap by Nao (Katsuki Mori), after her friend-with-benefit’s Sasaki (Shouma Kai) had his media career-plans derailed by Segawa failing him. Nao and Segawa however find unexpectantly common ground. Finally, ‘Once Again’ has Natsuko (Fusako Urabe) excitedly bumping into her former high school girlfriend Aya (Aoba Kawai) at a train station – only to find, when they return to Aya’s home, both have mistaken the other for someone else. These two strangers however find it easier to talk and bond.

All three of these stories are deceptively simple. Only ‘Once Again’ features any unusual set-up (a computer virus has rendered all computers unusable, a sci-fi insertion that only exists to remove any chance of the mix-up being avoided). Hamaguchi shoots each story with an unaffected simplicity, frequently employing long-takes and staging the bulk of each story (each is about 40 minutes) in single, every-day locations – from taxis to offices to homes.

But Hamaguchi’s approach allows the performances to grow with a subtle, skilful naturalness, capturing intense (but often hidden) changes of mood in the slightest micro-expressions. Each of the three key conversations underpinning the stories develops in utterly unexpected ways and part of the magic of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is immediately wanting to play each of back and try and spot the moments where they changed their participants lives.

Hamaguchi carefully builds our empathy with these characters, using Ozu-inspired stationary set-ups complemented with unfussy two-shot set-ups, but culminating in moments of complete immersion where POV shots place us behind the eyes of each character, looking directly at the person they are talking with. It’s a superb way of quietly building our connection with the characters and the events they are experiencing and works brilliantly to immerse us in these moments that we know will shape their emotional development over months and years to come.

This gives these small scale – and they are defiantly small-scale – stories real impact. Hamaguchi’s film is about real people facing real problems: lost loves, frustrated ambitions, childhood regrets. The very human feelings in play here help make the stories affecting. It’s helped again by the subtle performances Hamguchi draws from the cast. When Meiko – a marvellous ambiguous Kotone Furukawa – fumes against her ex-boyfriend for moving on, is she angry at him or at herself for letting him go? Does Segawa (a perfectly dour, almost unreadable Kiyohiko Shibukawa) feel fear at his reputation being damaged or because of stirrings of sexual longing he has clearly repressed? Does Natsuko (a gorgeously fragile Fusako Urabe) relish the freedom of speaking her mind to a complete stranger even more than she would talking to the actual person she is recalling?

Hamaguchi mixes this with intriguing moments of fantasy. A deliberately clumsy camera zoom at one point indicates to us a no-holds-barred conversation in a café has just been in the imagination of one of its participants. Sasaki fantasises about himself reporting on the television about his former mentor. Hamaguchi also brings a wonderful sense of magic to everyday locations (not to mention the fairy tale like set-up of the final stories lack of computers, which feels like the aftereffects of a witch’s curse). The escalator Natsuko and Aya meet on takes on a mystic beauty as it moves them past each other on careful tracking shots. Meiko walks through city streets and stares back at a skyline that feels filled with meaning. Hamaguchi isn’t afraid to slow the film down at key moments to soak up atmosphere and observe the everyday beauty in objects around us.

It lends even more power to the sudden changes these characters experience. Each story carefully builds on the emotional impact of the one before, taking us through ambiguity to complex mixed feelings to a final cathartic moment at a train station that carries real emotional force. Every story ends in a very different place from what we expected at the start – or arguably even the middle – without Hamaguchi ever overplaying his Dahlish Tales of the Unexpected card.

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is a small-scale expression of Hamaguchi’s directorial mastery, a perfect expression of his ability to infuse small-scale stories with great emotional force and psychological depth. It’s a highly skilled piece of short-film-making, pulled together into an effective collection. A clear indicator that this – combined with Drive My Car – marks Hamaguchi out as a future great.