Villeneuve’s triumphant sequel continues to raise the bar for science fiction films

Director: Denis Villeneuve

Cast: Timothée Chalamet (Paul ‘Muad-Dib’ Atreides), Zendaya (Chani), Rebecca Ferguson (Lady Jessica), Javier Bardem (Stilgar), Josh Brolin (Gurney Halleck), Austin Butler (Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen), Florence Pugh (Princess Irulan), Dave Bautista (Rabban Harkonnen), Christopher Walken (Emperor Shaddam IV), Léa Seydoux (Lady Margot Fenring), Souheila Yacoub (Shishakli), Stellan Skarsgård (Baron Vladimir Harkonnen), Charlotte Rampling (Gaius Helen Mohaim)

Denis Villeneuve had already taken on the near-impossible in adapting the unfilmable Dune into a smash-hit admired by both book-fans and initiates. In doing so he set himself an even greater task: how do you follow that? Dune Part 2 (and this is very much Part 2, picking up minutes after the previous film ended) deepens some of the universe building, but also veers the story off into complex, challenging directions that fly in the face of those expecting the sort of “hero will rise” narrative the first Dune seemed to promise. Dune Part 2 becomes an unsettling exploration of faith, colonialism and cultural manipulation, all wrapped up in its epic design.

Paul (Timothée Chalamet) and his mother Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) have escaped the clutches of their rivals House Harkonnen and it’s corrupt, sadistic leader Baron Vladimir (Stellan Skarsgård). Escaping into the deserts of Arrakis, they take shelter with the Fremen, vouched for by tribal leader Stilgar (Javier Bardem). It transpires Paul fits many of the conditions of the prophecy of the Mahdi or Lisan al Gaib, the promised messiah of the Fremen. Paul is uncomfortable with this – and the growing devotion of the likes of Stilgar – but also recognises the potential this has for marshalling the Fremen for his own revenge on the Harkonnen’s. Its further complicated by his knowledge the prophecy was embedded into their culture by the mysterious Bene Gesseri, the religious order that quietly controls much of the Empire, not to mention the hostility of Chani (Zendaya) the woman he loves, as she believes the Fremen should save themselves not rely on an outsider.

These complex ideas eventually shape a film that avoids simple good-vs-evil narratives and subtly undermines the very concept of the saviour narrative. Dune’s roots in a mix of Lord of the Rings and Lawrence of Arabia have rarely been clearer. Not least in the perfect casting of the slightly androgenous and fey Timothée Chalamet as Paul (with more than a hint of Peter O’Toole), barely knowing who he is, drawn towards and standing outside an indigenous community based on strong tribal loyalty, tradition and the grim reality of life in a hostile environment.

A large part of Dune 2 deconstructs Paul’s heroism and his (and Jessica’s) motives. When Jessica – who takes on a religious figurehead role with the Fremen – starts stage-managing events to exactly match the words of the prophecy, does that count as a fulfilment? Paul is deeply uncomfortable with positioning himself as messianic figure for an entire race, effectively weaponising their belief for his own cause. But he’s also nervous because he is also an exceptionally gifted person with powers of persuasion and prophetic insight that mark him out as special. As Paul allows himself to more-and-more accept the role he has been groomed for, how much does it corrupt him? After all, he gains absolute power over the Fremen – and we all know what that does to someone…

Paul’s messianic possibility is also spread on very fertile ground. Javier Bardem’s Stilgar represents a large portion of the Fremen population, who belief in this prophecy with a fanatical certainty. The dangers of this is subtly teased out by Villeneuve throughout the film. At first there is a Life of Brian comedy about Stilgar’s wide-eyed joy as every single event can be twisted and filtered through his naïve messiah check-list (“As is written!”) – even Paul’s denial he is the messiah is met with the response that only a messiah would be so humble! This comedy however fades as the film progresses and the militaristic demands Paul makes sees this same belief channelled into ferocious, fanatic fury that will leave a whole universe burning in its wake.

Much of Paul’s hesitancy is based on his visions of a blood-soaked jihad that will follow if he indeed “heads south” and accepts the leadership of the Fremen’s fanatical majority. The question is, of course, whether the desire for revenge – and, it becomes increasingly clear, a lust for power and control – will overcome such scruples. Part of the skill of Chalamet’s performance is that it is never easy to say precisely when your sympathy for him begins to tip into horror at how far he is willing to go (Villeneuve bookends the film with different victorious armies incinerating mountains of corpses of fallen foes), but in carefully calculated increments the Paul we end up at the end of the film is a world away from the one we encountered at the start.

Villeneuve further comments on this by the skilful re-imagining of Chadi, strongly played by Zendaya as an intelligent, determined freedom-fighter appalled at the Fremen exchanging one dogma for another. In the novel a more passive, devoted warrior-lover of Paul, in Dune Part 2 she becomes effectively his Fremen conscious, a living representation of the manipulation Paul is carrying out on these people. In her continued rejection of worship – even while she remains personally drawn to Paul – she provides a human counterpoint to Paul’s temptation to follow his father’s instructions and master “desert power” to control the worlds around them.

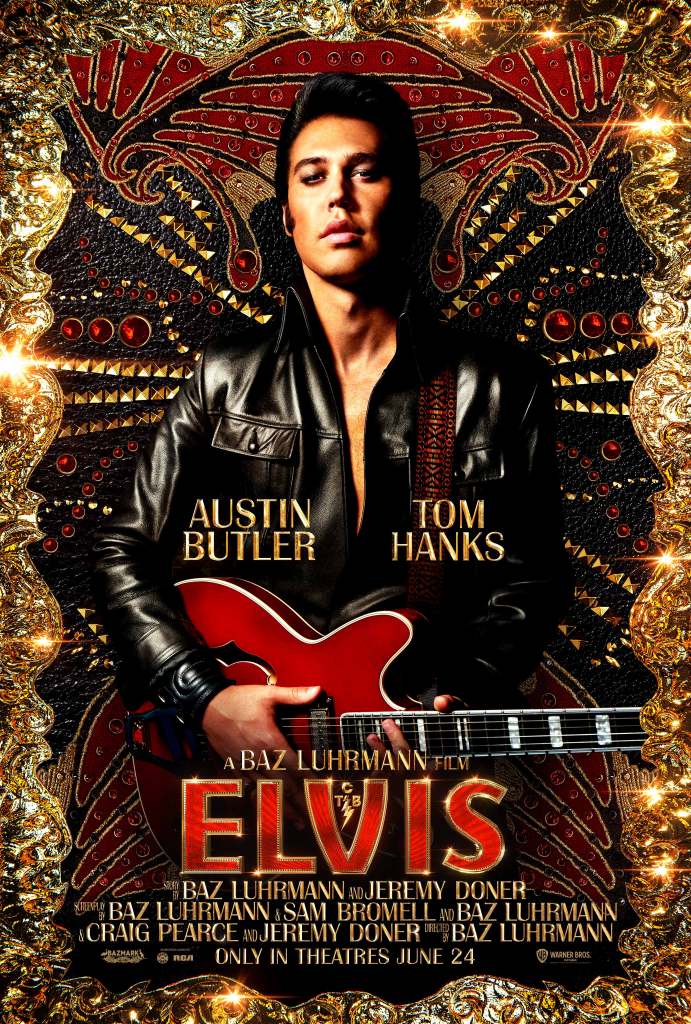

Deplorable and evil as the Harkonnen’s are, do Paul’s ends justify his means? And where does it stop? Dune Part 2 sees the Harkonnen’s subtly reduced in status. Dave Batista’s brooding Raban proves an incompetent manager of Arrakis. Stellan Skarsgård’s Baron is crippled by an assassination attempt and increasingly buffeted by events rather than controlling them. The film’s clearest antagonist becomes Austin Butler’s chillingly psychopathic junior Baron Feyd-Rautha, a muscle-packed bald albino, obsessed with honour and utterly ruthless towards his own subordinates. (Introduced in a stunningly shot, black-and-white gladiatorial combat scene that showcases his insane recklessness and twisted sense of honour.) But increasingly they feel like minor pawns in a game of international politics around them.

Villeneuve allows Dune’s world to expand, delving further into the cultural manipulations of the Bene Gesserit. This ancient order not only controls the Emperor – a broodingly impotent Christopher Walken – but also manipulates the bloodlines of great houses for their own twisted breeding programme, as well as inject cultures like the Fremen with perverted, controlling beliefs. While Villeneuve still carefully parses out the world-building of Dune – you could be forgiven for not understanding why the Spice on Arrakis is so damn important – it’s a film that skilfully outlines in broad strokes a whole universe of backstairs manipulation.

Among all this of course, Dune remains a design triumph. Grieg Fraser’s cinematography ensures the desert hasn’t looked this beautiful since Lawrence. The production and costume design are a triumph, as is Hans Zimmer’s imposing score. Above all, the film is brilliantly paced (wonderfully edited by Greg Walker) and superbly balanced into a mix of complex political theory and enough action and giant worm-riding to keep you more than entertained.

Dune Part 2 is a rich and worthy sequel, broadening and deepening the original, as well as challenging hero narratives. It turns Paul into an increasingly dark and manipulative figure, whose righteous anger is only a few degrees away from just anger (he’s no Luke Skywalker), who starts to see people as tools and moves swiftly from asserting Fremen rights to asserting his own rights (overloaded with different names, its striking when Paul chooses to use which names). In a film that provokes thoughts and thrills, Villeneuve’s Dune continues to do for fantasy-sci-fi what Lord of the Rings did for fantasy, creating a cinematic adaptation unlikely to be rivalled for decades.