Dreadfully pleased with itself and full of shallow insights and stunt clickbait moments

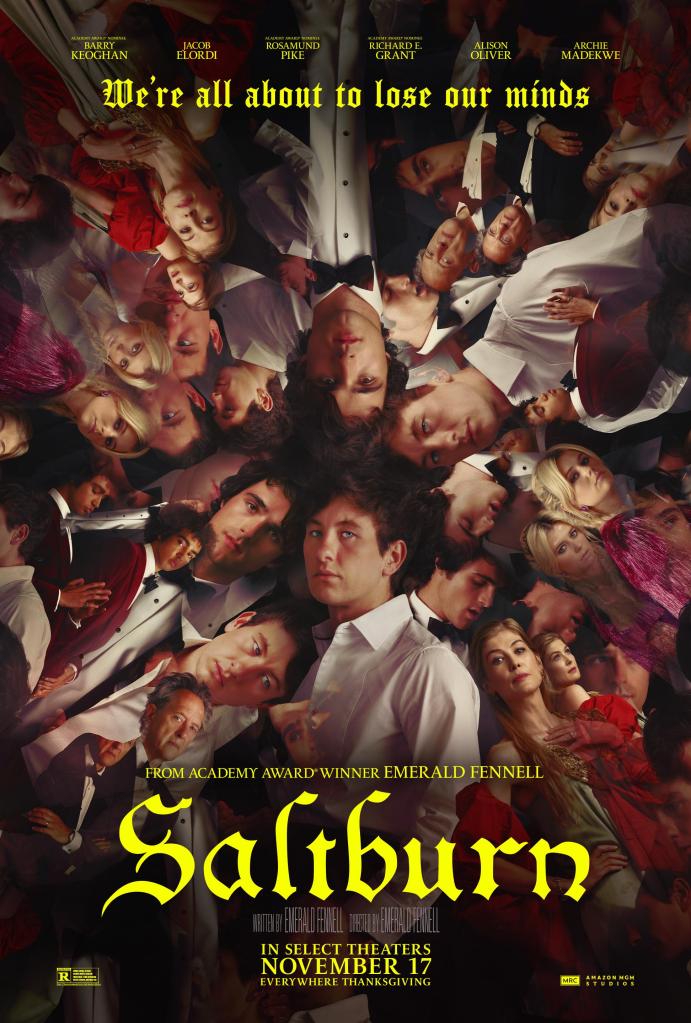

Director: Emerald Fennell

Cast: Barry Keoghan (Oliver Quick), Jacob Elordi (Felix Catton), Rosamund Pike (Lady Elspeth Catton), Richard E Grant (Sir James Catton), Alison Oliver (Venetia Catton), Archie Madekwe (Farleigh Stuart), Carey Mulligan (“Poor Dear” Pamela), Paul Rhys (Duncan), Ewan Mitchell (Michael Gavey), Sadie Soverell (Annabel), Reece Shearsmith (Professor Ware), Dorothy Atkinson (Paula Quick)

Promising Young Woman was a thought-provoking, very accomplished debut. It’s odd that Emerald Fennell’s sophomore effort plays more like a first film: try-hard, style-over-substance, very pleased with itself and its punky attempts to shock. Crammed full of moments designed to be snipped out and talked about – in a “you will not fuckin’ believe what just happened” way – Saltburn is a fairly trivial remix of ideas much, much better explored elsewhere, predictable from its opening minutes.

It’s 2006 and Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) is a scholarship student at Oxford University, socially awkward and very conscious of his Liverpudlian roots, struggling to fit in among the wealthy set that dominates his college. At the centre is Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), fundamentally decent but blithely unaware of his privilege, who takes a shine to Oliver with his shyness, troubled working-class background and grief at the recent death of his alcoholic father. Felix invites Oliver to spend the summer at Saltburn, his luxurious family seat. There Oliver is welcomed – or does he inveigle his way? – into the lives of the Cattons, from seducing Felix’s sister Venetia (Alison Oliver) to charming his parents Sir James (Richard E Grant) and Lady Elspeth (Rosamund Pike). But is Oliver all he appears to be?

The answer, of course, is no. Which shouldn’t surprise anyone who has ever really encountered any form of unreliable narrator before. Fennell opens the film with a clearly older, well-dressed Oliver recounting the film’s story to an unseen person. It’s not much of a deduction from this alone, that Oliver is at best not to be trusted, is definitely potentially dangerous and is probably a lot worse. All that, inevitably plays out, in a film that so nakedly rips off Brideshead Revisited (or Recycled) and The Talented Mr Ripley that Oliver might as well be called Ripley Ryder.

“Ryder” would at least have been a witty name for a character who spends most of the film putting his (apparently) well developed manhood to effective use in manipulating and controlling people. Saltburn assembles a series of “shocking” moments of sexual weirdness from stalker-like sociopath Oliver – so much so, that the moments he merely wanders (or dances) around in the buff feel almost normal. Surely there was more than half an eye on hashtags when the film presents scenes like Oliver drinking spunky bathwater, performing oral sex on a woman during her period or dry humping then wanking over a grave. It’s not big and it’s not clever.

“Not clever” also sums up the film’s inane social commentary. Set in 2006, it seems to take place in a version of Oxford that probably hasn’t existed since 1956. Having been in a state-school kid at Oxbridge at this time, its vision of a university 98% populated by poshos jeering at working-class kids with the wrong sort of tux just isn’t true (in fact there were more state school students than private school kids at Oxford that year). In this fantasy, all the students are either from Old Etonians or maladjusted weirdos from state schools. It’s hard not to think this is Emerald Fennell (a woman so posh, her 18th birthday party was featured in Tatler) guiltily looking back at how her “set” at Oxford might have behaved to the less privileged students.

It boils down to a view of Oxford as an elitist social club laughing openly at anyone who can’t trace their descendants back to the House of Lords, where tutors are entranced by the idea that a place like “Liverpool” exists and snort at the working class student for being a clumsy try-hard by actually reading the books on the reading list with student life flying by in a series of hedonistic raves, hosted by the rich and famous. Maybe I was just in the wrong circles back in the day.

This portrait of Oxford as a play pen for the super elite is as damaging (it’s exactly the sort of false image that stops deserving people from wanting to go) as it is lazy, tired and false. But then, Saltburn compounds its boringly seen-it-all-before social commentary by trudging off down other, all-too-familiar paths as it turns its fire on those with their nose pressed up against the window of privilege. The film’s vilest member of the elite, Farleigh, is himself an interloper, turned aggressive gate-keeper. And, as is not a surprise, Oliver’s roots turn out to be far more comfortable than he is letting on. Oliver is a Charles Ryder who yearns for Brideshead so much, he starts destroying the Marchmain family to get it. Because, in his eyes, as an aspirant middle-class type he appreciates it more.

On top of this is layered a clumsy, Ripley-esque madness to Oliver, who can’t decide himself whether he is infatuated with the charming Felix (very well, and sympathetically, played by Jacob Elordi) or just wants to suck his soul dry. Barry Keoghan plays this Highsmith-styled sociopath with just enough flash and sexual confusion – and he does manage to successfully turn on a sixpence from wide-eyed wonder, to vicious anger. But the character again feels like a remix of something done better elsewhere, trading emotional depth for cartoonish bombast and clumsy on-the-nose point scoring.

The on-the-nose-ness runs through the whole film. It’s a film screaming to be taken seriously, from its 4:3 framing, to its jarringly satirical music choices, arty Gothic fonts, visual quotes from Kubrick and look-at-me love of tricksy camera shots (some of these, I will admit, are gorgeously done, even if the film frequently lingers on them so we can “see the work”). But it makes very little sense. How does Oliver manage to exert an influence, so profound and complete, over Felix’s parents? Why does the wool fall from everyone’s eyes one-at-a-time in quick succession? Does Saltburn feel sorry for the generous but emotionally dysfunctional Cattons or does it feel they deserve their fate?

Because so many of these ideas are so half-heartedly explored, it becomes a collection of scenes designed to shock, tricksy directorial decisions, some flashy performances (Rosamund Pike can certainly wittily deliver a slew of lines dripping with blithely unaware privilege) and twists that will only surprise those who have never seen a story about an outsider before. Jacob Elordi emerges best, creating a character of surprisingly revealed emotional depth, but most of the rest of Saltburn settles for flash and instant gratification. To use its own terms of reference, it’s as satisfying as premature ejaculation: fun for an all-too-brief second, then a crushing, shameful disappointment.