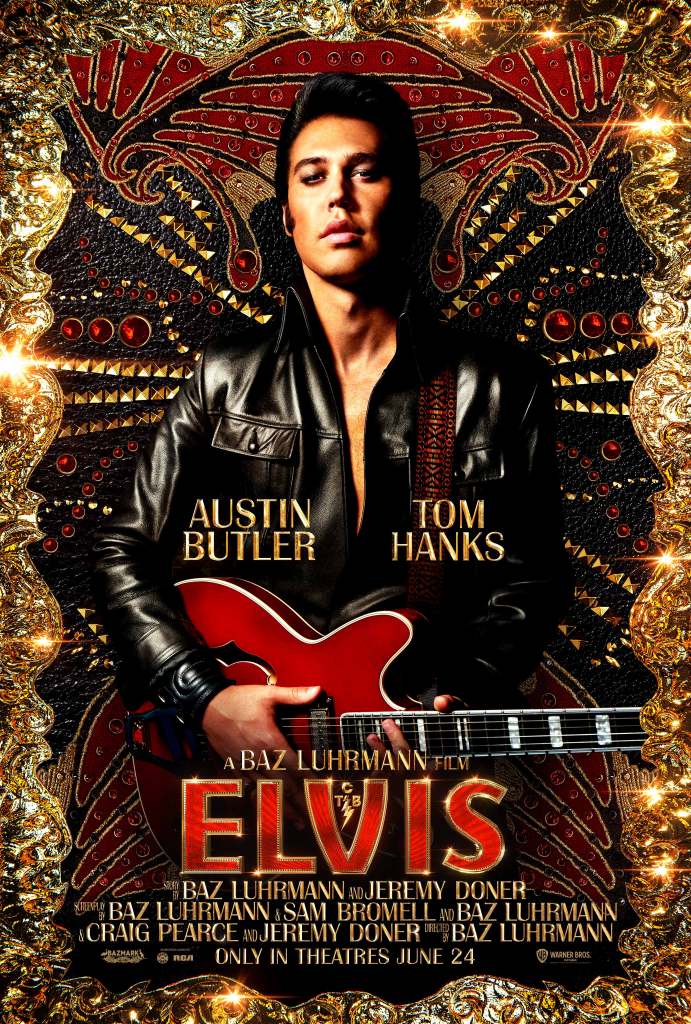

A brash, confident exterior hides a more sensitive and tender film – rather like its subject

Director: Baz Luhrmann

Cast: Austin Butler (Elvis Presley), Tom Hanks (Colonel Tom Parker), Olivia DeJonge (Priscilla Presley), Helen Thomson (Gladys Presley), Richard Roxburgh (Vernon Presley), Kelvin Harrison Jnr (BB King), David Wenham (Hank Snow), Kodi Smith-McPhee (Jimmie Rodgers Snow), Luke Bracey (Jerry Schilling), Dacre Montgomery (Steve Binder)

You know someone has reached an untouchable level of fame, when their first name alone is enough for everyone to know who you’re talking about. Few people are as instantly recognisable as Elvis. He had such impact, that the world is still awash with impersonators decades after he died. He’s an icon like few others – perhaps only Marilyn Monroe can get near him – and if Baz Luhrmann’s ambitious, dynamic biopic only at times feels like it has really got under his skin, it does become an essential, tragedy-tinged tribute to a musical giant.

Its slight distance from its subject is connected to Luhrmann’s choice of framing device. This is the life of legend, as told by the man behind the curtain who pulled the strings. The film opens in the final moments in the life of Elvis’ manager, Colonel Tom Parker. Whisked to hospital after a terminal stroke, Parker sits (hospital gown and all) in a Las Vegas casino (standing in as his own personal purgatory), bemoaning that everyone blames him for Elvis’ death and he never gets the credit for giving the world the genius in the first place.

Like a mix of Salieri and Mephistopheles, Parker is a poisonous toad, a cunning “snowman” who spins spectacles at travelling fairs with Elvis as his ultimate circus “geek”, a peep show for the whole nation. Played by Tom Hanks under layers of prosthetics, with a whining, inveigling voice and a mass of self-pitying justifications, he is an unreliable narrator who we should be careful to listen to (a neat way of justifying any historical amendments). It also helps prepare us for one of the film’s main themes: Elvis is a man so trapped by what others want, he doesn’t even get to tell his own life story.

You can’t argue Luhrmann isn’t a polarising film maker. Elvis starts, as so many of his films do, with an explosion of frentic, high-paced style. The camera sweeps and zooms, fast cuts taking us through the final fever dream of the dying Parker, 60s-style split screens throwing multiple Elvis’ up on the screen. It’s a loud, brash statement – much like that visual smack in the face that opens Moulin Rouge! You either love or loath Luhrmann’s colourfully brash style – love it and you are in for a treat.

Like Luhrmann’s other films, the attention-grabbing start is our doorway into a sadder, quieter, more reflective film. The early sweep of the camera, zooming in to Parker’s eyes and whirligigging around his giggling frame as he wheels himself through a casino, the transitions to comic-book style visuals, the location captions that loom over the scenes… it all builds to a sad, depressed and trapped Elvis sitting alone in his hotel room in America’s city of sin. Elvis is a film about an abusive relationship between two people, where the victim can’t imagine life without his Svengali. It’s Romeo and Juliet – but if Romeo was a poisonous succubus draining the lifeforce of Juliet.

Luhrmann is a master of quick establishment and has the confidence to make scenes that really should be ridiculous, work wonderfully well. The key musical influences on Elvis – the blues and Gospel – are introduced in a neat scene which shows the young Elvis moving from one to another on the same afternoon. His first performance captures the world-changing impact of the sex appeal of those swivelling hips by Luhrmann cutting to women, almost surprising themselves, by jumping out of their seats screaming and then looking around stunned at their reaction, before screaming again. It conveys whole themes in cheekily constructed vignettes like this.

It’s the same with stressing the obligations and influences that fill Elvis’ world. His dependence on the affection of a series of women – from his tough but demanding mother (strongly played by Helen Thomson) and then his loving but frustrated wife Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge) – is equally well established, as is Parker’s skill in sidelining these figures. The film deftly explores Elvis’ musical influences and that his success partly stemmed from being a white man singing black music. It’s an attraction Parker instantly picks up, and if the film does skirt over some of the more complex feelings of the black community towards this white singer, it does make Elvis’ debt to them hugely clear.

Luhrmann’s film takes a cradle-to-grave approach but manages to be a lot more than just jukebox musical. While there are performances – impressively staged and recreated – the music is used more to inspire refrains and ideas in the score rather than shoe-horned in as numbers. It’s a skill you wish the script had a little more of at times. Elvis doesn’t always quite manage to tell you about the inner life of this icon. We begin to understand his dreams of leaving a mark, but little of his motivations. His feelings for his wife are boiled down to a simple lost romance and his opinions on everything from politics to family dynamics (both subjects the real Elvis was vocal about) remain unknowable.

But this is film that focuses on the tragedy of an icon. And it makes clear that Parker – whose bitter darkness becomes more and more clear from the beginning – was responsible for crushing the life from a man who he turned into a drugged showpony, in a glittering Las Vegas cage. Parker and Elvis’ first meeting is a beautifully shot seduction atop a Ferris wheel, and helps cement in the viewer’s minds the power this man will have over the King’s life and career.

Crucial, perhaps above all, to the success of the film is Austin Butler’s extraordinary, transformative performance. This is sublime capturing of Elvis’ physicality, but he matches it with a beautifully judged expression of the legend’s soul. His Elvis is always completely believable as the most famous man on the planet, but also a conflicted, slightly lost man under the surface, lacking the confidence to build his own destiny. Butler’s recreation of Elvis’ singing is extraordinary and his performance bubbles with an unshowy tragedy. He breathes life into this larger-than-life icon in a subtle and eventually deeply affecting way that will make you want to throw an arm around his shoulder.

Luhrmann’s film ends a world away from its bright beginning. We’ve seen Elvis triumph, but we’ve also seen him buffeted by events, never really becoming their master. Elvis becomes a highly emotional tribute to a man who gave us so much, but was prevented from giving more. When the real Elvis appears on screen, singing Unchained Melody with passion, it’s undeniably moving. Even more so because we get a sense that performances like this was what we wanted to be doing. Luhrmann – and Butler, whose work cannot be praised enough – may not always manage to make us know the King as completely as we could, but it certainly makes us care deeply and share his regret.