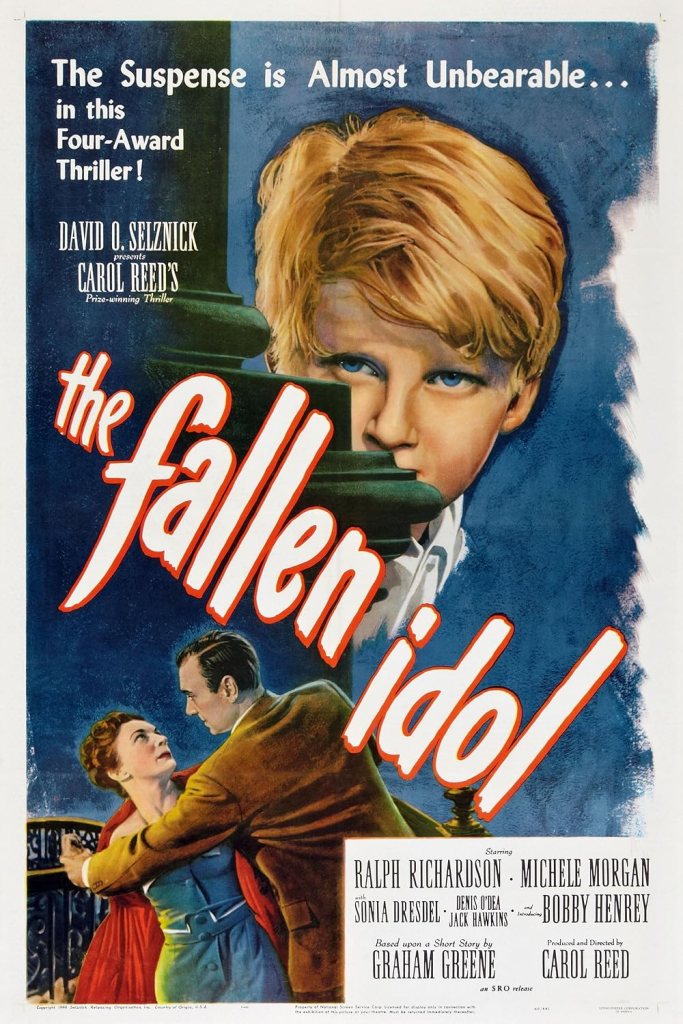

Brilliant thriller about how hard the world is for a child to understand

Director: Carol Reed

Cast: Ralph Richardson (Baines), Michèle Morgan (Julie), Sonia Dresdel (Mrs Baines), Bobby Henrey (Philippe), Denis O’Dea (Chief Inspector Crowe), Jack Hawkins (Detective Amos), Walter Fitzgerald (Dr Fenton), Dandy Nichols (Mrs Patterson), Geoffrey Keen (Detective Inspector Davis), Bernard Lee (Inspector Hart), Dora Bryan (Rose), Karel Stepanek (First Secretary), Torin Thatcher (Constable)

We’ve all had heroes we worship haven’t we? Few hero worships burn as brightly as a child’s. Eight-year-old Philippe (Bobby Henrey), son of a foreign ambassador in London, is awe-struck by the embassies English butler Baines (Ralph Richardson), a kind, decent man with a twinkle in his eye who enjoys spinning stories for Phil about his exciting life in India. The highlight of Phil’s day is spending time in Baines’ parlour. For Baines though, his highlights are the snatched moments of release from his domineering, unloving wife (a masterfully tough-to-like Sonia Dresdel) that he spends with embassy secretary Julie (Michèle Morgan).

The affair is obvious to us in seconds. But Phil – from whose perspective we see large amounts (but, crucially, not all) of the film play-out – is of course oblivious, readily accepting Baines awkward assurance Julie is just his niece. The Fallen Idol – the middle film in Reed’s astonishingly high-quality run of films that includes Odd Man Out and The Third Man – is a brilliantly tense, very moving story of how adrift children feel in the adult world, how easily they misinterpret signals and misread social cues. Superbly filmed, with a wonderful script by Graham Greene (from his own novel) it’s a masterclass in how the simplest situation can lead to the most intense drama.

It revolves around a fatal trap for Baines. Believing his wife is away for the weekend (she has in fact concealed herself in the embassy mansion), Baines treats himself to a day and night with Julie. Discovered, the confrontation leads to Mrs Baines dead at the bottom of the stairs. The argument is partially witnessed by Phil – but crucially, only glimpses of it as he runs down the exterior fire escape, peering in through windows as he goes – but in full by the viewer. It’s clearly a terrible accident, taking place after Baines had left. But Phil is convinced he has witnessed a murder – and so passionate is his hero worship of Baines (and loathing of Mrs Baines), he decides to do everything he can to protect the butler.

The genius of Reed’s The Fallen Idol is that we are always know more than any of the characters. Just as we can tell immediately from witnessing Baines and Julie’s whispered, Brief Encounter-ish meeting in a London coffee shop that they are in the midst of a passionate affair, so we also know much faster than any character that Mrs Baines is still in the house and that her death is a clumsy accident. We can also see, in ways Phil cannot, that his desperate lies only undermine Baines honest version of events. We know all the details well ahead of the police, watching them misinterpret clues and behaviour in the worst possible light. The entire film shows how damning circumstances and coincidences can fold up into a vice-like trap from which there is almost no escape.

The Fallen Idol is a film awash with lies. In many ways it’s a heartbreaking reveal of how quickly the compromises and selfishness of the adult world corrupts the child’s. At the heart of these lies is Baines himself. The role is beautifully played by Ralph Richardson, utilising his eccentric cuddliness to exceptional effect, but also perfectly capturing the selfishness, weakness and cowardice of Baines. Because Baines is a liar – not only to his wife, but also to Julie (he spectacularly lacks the guts to ask his wife for a divorce, despite what he tells Julie) and, walking Phil back after he has crashed Baines’ tea-time meeting with Julie, urgently instructs him to lie if he is ever asked about what happened that afternoon. Baines doubles down on his duplicity by using the unwitting Phil as a shield to cover a zoo-trip date with Julie, and even his adventure stories to Phil are all slightly self-aggrandizing tall tales.

One of the toughest things about The Fallen Idol is that hero-worship is a confused one-way street, especially when children are involved. Baines is fond of Phil but often treats him with distracted affection out-of-kilter with the earnest, devoted adoration Phil pours on him. This devotion from Phil is so great, even his belief that his hero is a murderer makes no impact on him. Having taken his idol’s lessons to heart, about what to do when questioned about anything to do with Julie, Phil lies and lies to the investigating officers, corrupting himself (he believes, after all, he is helping a killer) while also making the innocent Baines seem guiltier-and-guiltier with every word.

Carol Reed draws a superbly natural performance from Bobby Henrey, in a performance utterly lacking in childish, mannered acting tricks. It’s a hugely natural performance, over-flowing with innocence making Phil a character we end up deeply caring for. The early half of the film throws us perfectly into the excited world of a child with a whole mansion to run around in, cuddling his pet snake close to his chest. Reed also brilliantly captures how a moment of trauma confuses and terrifies an innocent into not knowing what action to take. Fleeing the house barefoot – clearly terrified and heartbroken – immediately after the death, Phil is petrified when he encounters a policeman not because he is intimidated, but because he fears inadvertently betraying his idol.

Reed superbly captures the desperate vulnerability of children, the nightmare of not having your voice listened to as adults talk over and around you. The Fallen Idol (with its careful use of disjointed angles and God-like, wide-angle shots from above) has a superb sense of the horror of being caught in a situation you neither fully understand or can influence. It’s echoed perfectly by Baines’ increasingly defensive panic as each denial falls on all-too-obviously deaf ears. Phil also misinterprets almost everything he is told in the film, right up to when the sympathetic Julie (a lovely, warm performance from Michèle Morgan) begs him that only the truth can help Baines.

The Fallen Idol spices this up with superb moments of comedy. Dora Bryan has a delicious cameo as a ‘lady of the night’, called upon to by the flummoxed policemen at the station Phil has fled to, to try and draw some words out of the stubbornly silent child – and who can only fall back on the cliches of her profession (‘Can I take you home dearie?’). An Inspector (a lovely cameo from Bernard Lee) called in to translate in the embassy is begged by the first secretary to drop his inept schoolboy French. A tense interrogation of Baines is interrupted when a pedantic embassy staffer insists he must be allowed to check the clocks in the room (Reed wittily shows the characters revolving, clockwork like, impatiently on the spot in the background while this interminable check goes on).

But the great strength of The Fallen Idol is how it captures the joyful innocence of childhood and the Kafkaesque confusion the adult world can have on a child. Poor Phil never really understands anything that goes on (although the film ends with a sweet irony of Phil being the only person who perhaps understands a vital ‘clue’ only to be completely ignored) while we are always in complete understanding. Reed’s direction is faultless, both from his work with actors to his masterful use of camerawork and editing to really capture the confusing, unreadable adult-world from a child’s perspective. It’s a masterful, gripping, heart-rending film – a small scale classic that perfectly mixes tension and wit.