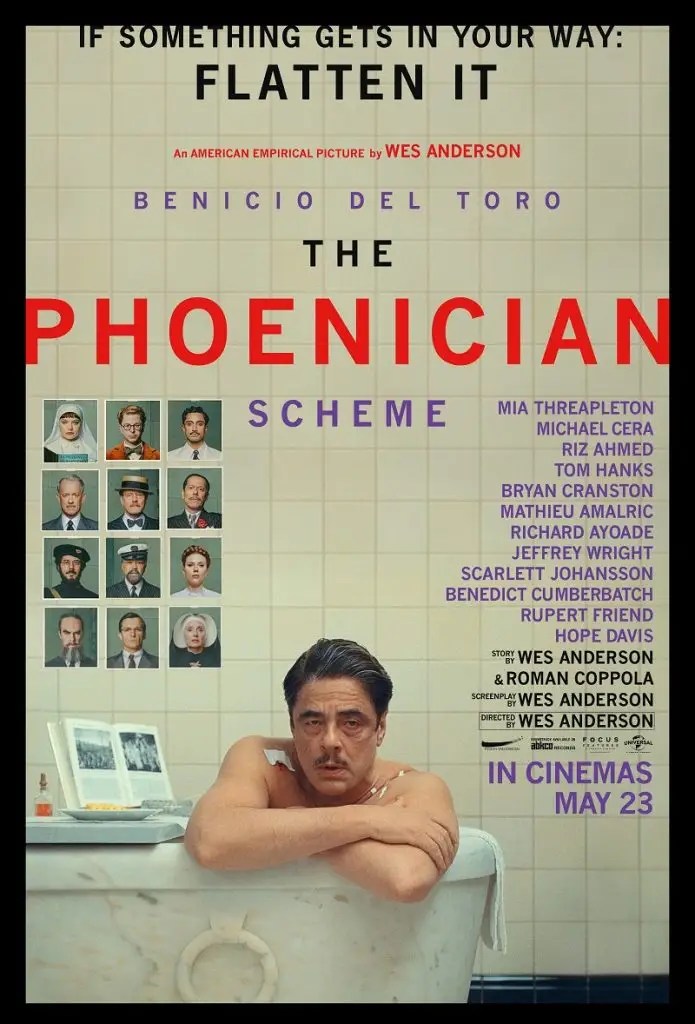

Anderson marries heart, truth and a genuinely engaging and compelling plot with his unique quirk

Director: Wes Anderson

Cast: Benecio del Toro (Zsa-Zsa Korda), Mia Threapleton (Sister Liesl), Michael Cera (Bjorn Lund), Riz Ahmed (Prince Farouk), Tom Hanks (Leland), Bryan Cranston (Reagan), Mathieu Amalric (Marseilles Bob), Richard Ayoade (Sergio), Jeffrey Wright (Marty), Scarlett Johansson (Hilda Sussman), Benedict Cumberbatch (Uncle Nubar), Rupert Friend (Excalibur), Hope Davis (Mother Superior), Bill Murray (God), Charlotte Gainsbourg (Korda’s late wife), Willem Dafoe (Knave), F. Murray Abraham (Prophet), Stephen Park (Korda’s pilot), Alex Jennings (Broadcloth), Jason Watkins (Notary)

Wes Anderson is one of those directors I often sit on the fence about, with a style so distinctive it can in become overwhelming. But when it works, it works – and The Phoenician Scheme is (aside from his superb Netflix Dahl adaptations) his best work since his masterpiece The Grand Budapest Hotel. In this film, Anderson finds an emotional and story-telling engagement that adds depth to all the stylised invention. It’s a film I’ve found more rewarding the longer I’ve thought about it.

Set in an Anderson-esque 1950s (Andersonland?), notorious industrialist and arms trader Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benecio del Toro) spends his life dodging assassins. After one attempt gets close, he decides to try and repair his relationship with estranged daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), a novice nun who suspects her father might have had her mother murdered (he denies it). With governments, business competitors and others on his tail, Korda throws together a complex scheme for one last success in Phoenicia, a massive new development built with slave labour. As Korda juggles rivals and investors, will he repair his relationship with his daughter? And how will he fare in his recurrent visions of standing at the (noir) Gates of Heaven, being judged for entry?

Anderson’s film, of course, is another superb example of his visual style, constructed like an intricately layered work of art. Each shot could probably hang in an art gallery, framed to perfection with gorgeously sublime colours that soak off the screen. The elaborate set design and vintage costume work are striking as always, with every piece perfectly placed and every feature expertly judged. Within this, his carefully selected cast deliver the wry, dry and arch Anderson-dialogue with aplomb, embracing every moment (of many) where Anderson allows the characters to share a raised eyebrow or a pithy aside to the camera.

In other words, it might all be as you expect – a formula that started to feel a bit tired after intricate, insular films like The French Dispatch and Asteroid City, which felt so personal to Anderson that they were virtually impenetrable to everyone else. But what elevates The Phoenician Scheme is that Anderson embraces both a surprisingly tense plot-line – the closest he can probably get to a thriller, laced throughout with satire, humour and more than a fair share of the ridiculous – and gives a genuine emotional force to a father and daughter struggling to recognise what (if anything) could bring them together. Throw in questions around life, death and what constitutes making a life ‘worth living’ and you’ve got a rich, intriguing and rewarding film that could stand even without the Anderston scaffolding.

Perhaps only Anderson could mix an unscrupulous businessmen targeted by assassins (some of these are delightfully, blackly, comic – not least an opening plane bomb that sees Korda ejecting his pilot for refusing to attempt a crazy hail-Mary manoeuvre to survive an inevitable crash) with Korda closing vital deals (in a deliberately, impenetrably complex scheme) by shooting hoops with a pair of baseball-fanatic brothers (Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston, both hilarious), taking a bullet for a fez-wearing gangster (Matheiu Almaric, wonderfully weasily) and forcing an eccentric naval captain (Jeffrey Wright, perfectly deadpan) during a blood donation to sign with a bomb. And spin out a joke where Korda hands over custom-made hand grenades to business associates like they are branded pens. All while dodging a shady government cabal (fronted by Rupert Friend’s Transatlantic Arthurian-nick-named Excalibur).

But The Phoenician Scheme works because under this comic twist on spy thrillers, it has a real heart. Anderson’s finest films are where he works with an actor who can bring depth and feeling to the quirk. And here, he might just have brought out the best from an actor prone to a little quirk himself. Benecio del Toro gives Korda a world-weary cynicism but also a subtle fragility. There is nothing that won’t flummox Korda, a guy tipped off on attempts on his life because he frequently recognises assassins he’s hired himself in the past. But he’s also quietly afraid his life has been for nothing: that he is, in fact, not a rogue but an out-and-out villain ruining countless lives. And that God (in the form of, who else, Bill Murray) isn’t going to be welcoming up there.

It motivates a careful dance of reconciliation and grooming to take over his business with his estranged daughter Liesl, delightfully played by Mia Threapleton (with just the right mix of dead-pan flair for the dialogue, while giving it an arch warmth). Liesl imagines herself as distant from Korda as can be – the novice (literally) to his expert manipulator – but she turns out to have far more talent for Korda’s mix of chutzpah, disregard for rules and ruthless improvisation. Watching the relationship – and recognition – between these two (beautifully played by both actors) is very funny and also surprisingly sweet (you know its Anderson when a nun suddenly pulling a small machete out of her wimple is both oddly endearing and absolutely hilarious).

This sense of emotional development and personal and dramatic stakes is improved further by the celestial semi-trial (cue Willem Dafoe as an advocate angel), in a black-and-white heaven that mixes Powell and Pressburger’s Matter of Life and Death (surely the name Korda is no coincidence) and the imagery of Luis Buñuel. This all leads into a surprisingly gentle but affecting tale of redemption and second-chances, including an ending that feels surprising but also somehow completely, wonderfully inevitable and fitting,

The Phoenician Scheme may even be slightly under-served by its Andersonesque framing and design: after all it’s become easy to overlook the depths when the display is as extraordinary as this. When Anderson unearths a deeper meaning, working with masterful performers who can imbue his quirky, witty dialogue with heft, he can be one of the best out there. And do all that without sacrificing an air of charming whimsy, and building towards the most hilarious fist fight since Bridget Jones’s Diary (between del Toro and Cumberbatch’s tyrannically awful Uncle Nubar). Not a lot of directors can pull that off – and it’s a lovely reminder that Anderson at his best is an absolutely unique, wonderful gem in film-making.