Past traumas are uncovered and a gentle love story unfolds in Streisand’s extremely effective relationship drama

Director: Barbra Streisand

Cast: Nick Nolte (Tom Wingo), Barbra Streisand (Dr Susan Lowenstein), Blythe Danner (Sally Wingo), Kate Nelligan (Lila Ward Newbury), Jeroen Krabbé (Herbert Woodruff), Melinda Dillon (Savannah Wingo), George Carlin (Eddie Detreville), Jason Gould (Bernard Woodruff)

For many, La Streisand is easy to knock. She developed a reputation as difficult: controlling, demanding and perfectionist. But don’t we praise these qualities in men? Perhaps she has more than a point when she claims complaints against her are grounded in sexism. Her snubbing by the Academy – The Prince of Tides got seven nominations including Best Picture, but none for Streisand bar as Producer – certainly feels like a crusty boys’ club deciding there is no place at their big night for a strong-minded woman. Doubly unfair since Streisand deserves plenty of praise for a film as rich, heartfelt, moving and surprisingly funny as The Prince of Tides.

Tom Wingo (Nick Nolte) is a football coach in South Carolina, where his marriage to Sally (Blythe Danner) is drifting towards the rocks, largely thanks to Tom’s jovial inability to be emotionally open. He’s called to New York when his poet sister Savannah (Melinda Dillon) attempts suicide. To aid her recovery, Tom must talk to her psychiatrist about the traumas of their childhood. But Tom himself is far, far away from putting bottled-up pain behind him. Streisand plays the psychiatrist, Dr Susan Lowenstein, struggling in an unhappy marriage with an arrogant violinist (Jeroen Krabbé, being Euro-smug as only he can) and with a troubled relationship with her son Bernard (played by Streisand’s real-life son Jason Gould). Despite initial uncertainty, will a spark of romance flair up between Wingo and Lowenstein?

Well, if you listen to the luscious score by James Newton Howard for a few seconds, you can be pretty confident the answer will be “yes”. (But it’s fine – Lowenstein’s husband is an arrogant tosser and Wingo’s wife tearfully confesses her own affair; no need to worry about betrayal here.) Officially adapted from his own huge novel by Pat Conroy,working with Becky Johnston (though it was an open secret Conroy frequently confirmed that Streisand wrote the script), it distils a massive novel into a tightly paced, extremely well-made romance that feels, in many ways, a throwback to the “women’s pictures” of the 1940s. (Conroy was thrilled.)

The big difference is that the typical Bette Davis role is here played by Nick Nolte. This is an extraordinarily superb performance by Nolte: never before had I appreciated what a deeply soulful, sensitive performer he is, especially when he is called to play the “gruff” card so frequently. Nolte’s Wingo is a Southern, gentlemanly good-old-boy, a man’s man who laughs off trouble and moves with the physicality of a rough-and-tumble sportsman. But, under the surface, he’s a sensitive, vulnerable a man tortured by past traumas he can barely bring himself to think about and consumed with guilt, self-loathing and the inability to express his feelings.

In nearly every frame of the film, Nolte is sensational: endearing, funny, joyful (his dancing at a house party has a hilarious self-mockery to it) but also stand-offish and self-contained. The film revolves around key meetings between him and Streisand’s Lowenstein, which grow increasingly intense as the taciturn joker Tom, almost against his will, has his carefully mounted defences stripped away. We see nothing, by the way, of Lowenstein’s treatment of Savannah, so tightly focused is the drama on Tom’s story. While narratively sensible, this does mean that Savannah is reduced to little more than a narrative device.

It makes for effective drama, well directed by Streisand. It’s a film that mixes moments of shock – Tom seeing his sister’s bloodstains on her apartment floor or deflate into mumbling incoherence when pushed on his past – with moments of genuine warmth and sweetness. Heck even a heated argument between the two of them segues suddenly into something comic when Lowenstein impulsively throws an Oxford English Dictionary at him, damn near breaking his nose. It should also be noted Streisand unselfishly casts herself in the less showy role – essentially a feed for Nolte – and cedes the finest moments and meat of the film to him.

Perhaps that’s also partly why Streisand’s doctor is the least convincing part of the film. With her diva nails and famous features, no amount of dome-like-glasses ever really makes you forget you are watching one of the world’s icons pretend to be a psychiatrist. (Particularly as the film relies on the magic therapist trope so beloved of Hollywood, where gentle probing and quiet “what do you think” lines lead to huge emotional revelation.) If anything, she’s more convincing and comfortable as the socialite mum struggling with her dreadful husband and resentful son.

Why the son is quite as resentful as he is to his mother, is left a bit of a mystery. Nevertheless, Jason Gould does a decent job as a young man torn between playing the football he loves and fulfilling the musical promise his father expects. (He also has a great father-son chemistry with Nolte, who coaches him in football skills.) Much clearer is why Lowenstein is struggling with her ghastly husband. Jeroen Krabbé is beautifully, smackably, smug and condescending. So much so that I laughed heartedly at the film’s most crowd-pleasing moment, as Tom punishes him for his rudeness over a dinner party by juggling his priceless Stradivarius over the edge of a penthouse balcony.

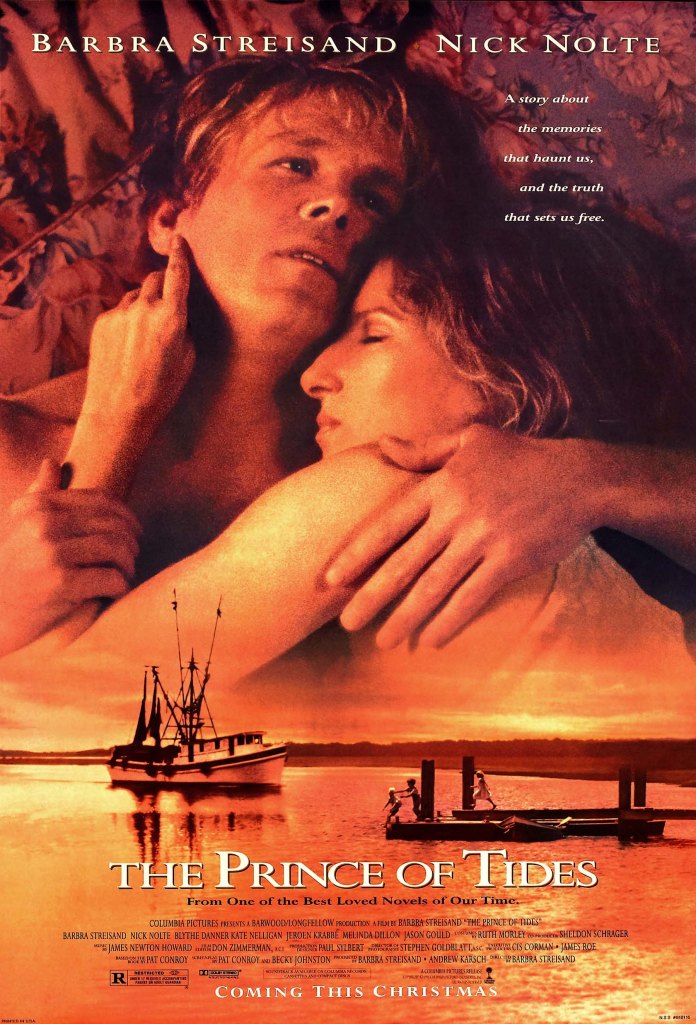

It makes it easy for us to accept Streisand’s eventual affair – much as Blythe Danner’s Sally regretfully confessing that Tom’s emotional closed-offness has driven her into the arms of another man. Despite the poster’s impression though, this is far from a steamy romance, waiting almost four fifths of its runtime before the two confess their feelings for a cathartic affair. For the bulk of the film, it’s an unspoken mutual affection, driven by Tom’s Southern flirtatious manner and Susan’s half-smiles. Again, it’s a slow-build, carefully paced romance that feels real.

Also because the film’s real build is not towards the two stars converting flirting to grinding, but in uncovering the exact trauma Tom is suppressing and has made him resent his mother (Kate Nelligan very good as an aspirant social-climber, refusing to invest love in her children) almost as much as his violent father (a surly Brad Sullivan). The reveal is, in some ways, expected – but also shockingly unexpected, particularly due to the visceral rawness which Streisand shoots the Nolte-narrated flashback with (Nolte is, needless to say, wonderful in this scene).

It’s part of the surprisingly effectiveness of a film that, in other hands, could have been a sentimental family drama, but is lifted by excellent, committed performances (Streisand is clearly a whizz with actors) and sensitive, patient direction. Streisand resists attention-grabbing flash, carefully letting scenes and emotions build, using subtle but effective camera movements. It comes together into a film that surprised me greatly with its richness. It eventually has a heart-warming message to tell of the power and importance of having the courage to admit your pain and emotions and, in its portrait of a man’s man engaging with his vulnerability, projects a message still powerful today. If Redford or Eastwood had directed it, they would have won an Oscar.