Earnest drama about racism, whose narrative perhaps focuses on less important issues and people

Director: Alan Parker

Cast: Gene Hackman (Agent Rupert Anderson), Willem Dafoe (Special Agent Alan Ward), Frances McDormand (Mrs Pell), Brad Dourif (Deputy Sheriff Clinton Pell), R. Lee Ermey (Mayor Tilman), Gailard Sartain (Sheriff Ray Stuckey), Stephen Tobolowsky (Clayton Townley), Michael Rooker (Frank Bailey), Pruitt Taylor Vince (Lester Cowans), Kevin Dunn (Agent Bird), Badja Djola (Agent Monk)

In June 1964 three civil rights workers – two white New Yorkers Andrew Goorman and Michael Schwerner and a black Mississippian James Chaney – were arrested, released and then murdered by Neshoba County law officials working alongside KKK white supremacists. An FBI investigation (codenamed Mississippi Burning) revealed the crime, arrested the criminals and managed to convict several (but not all) of them on the federal charge of violating civil rights (convinced the state charge of murder would lead to acquittal from racist juries). Mississippi Burning fictionalises this true-life atrocity into a hard-hitting thriller, mixed with the conventions of crime drama.

It’s directed by Alan Parker in the style of Midnight Express, pulling no punches in chucking the vileness of the KKK up on screen. During the course of Mississippi Burning we see Black people chased, beaten, flung out of moving cars onto the street, lynched and a praying child kicked in the face by a KKK thug. Rightly, the murderers are a vile parade of bullies, cowards and knuckle-dragging monsters portrayed by a group of actors (Dourif, Rooker, Sartain and Vince among them) used to going all-in on portraits of the scum of humanity. It’s a tightly directed, intense film – with a repetitively pounding score by Terry Jones – with Oscar-winning photography by Peter Biziou capturing the flame-lit night-time atrocities these repulsive people execute on innocents.

Mississippi Burning is undoubtedly well-made, with a very earnest message behind it. It’s impossible to fault its rightful disgust at the appalling injustice and racism, but you can’t help but feel it’s focusing its heroic lens on the wrong part of the story. It drew fire at the time for its fictionalisation of almost every element – wisely so in its portrayal of the initial crime, where their names and exact nature of their murder are altered – and the way this pushed the FBI (an organisation that had in many cases actively worked against civil rights) into a traditional heroic role, while reducing the Black people to passive recipients of beatings or kind words from whites. It’s hard not to feel today that, for all the skill of the film, the impact of those decisions have magnified the film’s flaws over time.

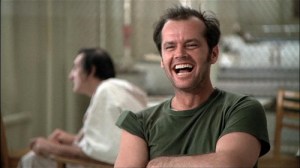

At heart, Mississippi Burning uses the conventions of a mis-matched buddy-cop investigative drama to add narrative drive to a social issues film. The two FBI agents are played so well by Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe, you barely notice both are stock roles straight out of central casting. Hackman gives such energy and life (with a lovely touch of shame that his own past conduct, as a Southern sheriff was presumably only a degree better than the people he’s investigating) to his role as no-nonsense, veteran maverick who understands the streets, that he transforms this cliché into a real person. Similarly, Dafoe plays the by-the-book, stuffy superior who has too learn rules-bending sometimes break the case, with such commitment you forget how role familiar it is.

The personal narrative of the film revolves around whether these chalk-and-cheese investigators will overcome their initial iciness – they address each other formally throughout the film and butt-heads frequently on the conduct of the investigation – to become a team which feels odd for a film where the other stakes (violent institutional racism) are so large. In many ways an alternative cliché – two disconnected investigators investing more in a case based on the injustice they see and the witnesses they talk to – might well have served it better and also reflected contemporary complaints that the FBI was more interested in the letter than the spirit of the law. Mississippi Burning does, at times, address this by having characters explicitly ask if the FBI would even lift a finger if two of the victims weren’t white. But seeing as the film generally considers raising the question the same as engaging with it, it doesn’t go anywhere.

The film requires the agents to undertake mis-steps in order to educate the audience (would Dafoe’s character really be as ignorant about the nuances of segregation as he frequently is here?) and blunder about for much of the early acts, most notably Dafoe’s public conversation with a Black man in a diner, that inevitably leads to the poor man kidnapped and beaten by the KKK. But on the whole, the FBI are presented as noble straight-shooters, aghast at the state of affairs in the South, rather than a body run by the morally-ambiguous J Edgar Hoover.

It also means Mississippi Burning relegates its Black characters to passengers and passive victims, reliant on white people for protection and vindication. While it would be false to claim the system in the South didn’t leave Black people largely powerless, the film’s failure to introduce a single memorable character giving voice to the Black perspective of a series of crimes that happened to them feels more and more uncomfortable as the film ages (particularly as the film’s hopeful ending very much places racism as a problem in the past, not a dilemma America continues to face).

The film’s real conscience (and the victim given most development) is instead Frances McDormand as the wife of Dourif’s vile racist sheriff. Parker’s film subtly indicating her lack of racism early (she consoling touches the arm of a Black man), and McDormand (who is excellent) brings real force to her pained, frightened longing to do the right thing. She contrasts neatly with the committed vile cowardice of Dourif, Rooker’s swaggering bullying and Stephen Tobolowsky’s Hiterlian racism as a KKK Grand Wizard. Parker successfully makes these guys so repulsive, that when Hackman’s Anderson gets free reign to intimidate, rough-up and bully them back it carries real satisfaction. But the film making the most developed victim of the film’s KKK a white, gentile feels more like filmmaker concerns that otherwise the bulk of the likely audience may otherwise have trouble relating to the bulk of the victims.

Mississippi Burning tries to be hopeful. This extends to some slightly forced moralising – the suicide of one character is attributed to guilt at the crime, rather than the more likely guilt at having ‘betrayed’ his fellow KKK – and a general sense that Mississippi is on the road to peace, feels a bit of a stretch for a region that had decades of continued unrest ahead. Saying that, in its sometimes clumsy way, you can’t doubt its power and its righteous disgust at racism. It’s well directed and has some excellent performances – Hackman and McDormand were both Oscar nominated – but it feels like a film that only focuses on part of an overall picture and not always the right part.