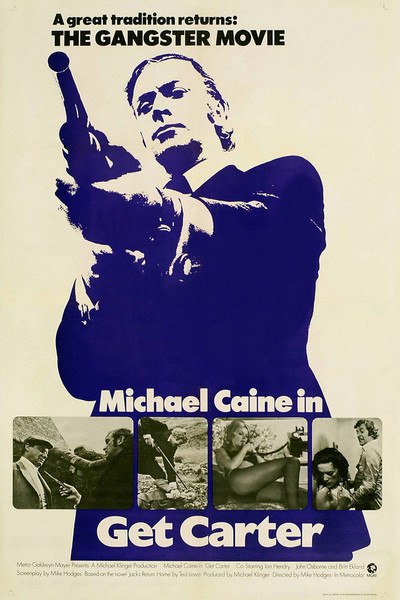

Brutal, dark and nihilistic British gangster film removes any chance that you might fancy trying a life of crime

Director: Mike Hodges

Cast: Michael Caine (Jack Carter), Ian Hendry (Eric), John Osborne (Kinnear), Britt Ekland (Anna), Brian Mosley (Cliff Brumby), George Sewell (Con McCarty), Tony Beckley (Peter the Dutchman), Glynn Edwards (Albert Swift), Alun Armstrong (Keith), Bernard Hepton (Thorpe), Petra Markham (Doreen), Geraldine Moffat (Glenda), Dorothy White (Margaret)

It’s probably the finest British gangster film ever made. Get Carter is a cold, dark, grimy film – a punch to the solar plexus, which completely rejects any sense of charm in its gangster characters. Michael Caine called Jack Carter a shadow Caine, the man he could have become if his life had broken out slightly differently. It’s set in an unremittingly bleak Newcastle, but it feels like it might be happening in an anti-chamber of hell, with its thoroughly amoral lead barely aware he’s spiralling towards destruction. It’s a sociopathic, Jacobean revenge tragedy set among the dirt filled suburbs of Newcastle.

Jack Carter (Michael Caine) is a professional fixer for London gangster brothers. He returns to his childhood home of Newcastle after the sudden death of his brother. But he’s not satisfied with the official explanation. Instead, he dives into an investigation, in which he cares not a jot about the collateral damage he causes or the likely reaction of the underworld powers that be as he rocks the boat to destruction, trashing the lives of everyone he meets, good and bad.

Powered by an extraordinary performance of blank nihilism and cold, unexpressed fury by Caine, nominally Jack is a man motivated by the harm done to his family. However, Hodges film is so cold-eyed and realistic about the mentality of gangsters, we know it’s just an excuse. Carter is never heart-broken, he’s annoyed. His brother may have been punished and his niece (it transpires) misused, but fundamentally what motivates Carter is the affront. By taking a pop at his family, he feels they really think they can take a pop at him. How dare they: he’s Jack Carter.

Any charm Carter has, solely comes from residual affection for Caine. By any measure, Carter is an awful man (even if he has a good turn of phrase). He is a sociopath with no concern for anyone. When friendly Keith (a young Alun Armstrong) is beaten black and blue for helping Carter, how does our hero respond? Tosses a few bank notes on his bed and tells him “buy some karate lessons”. Carter sees the world solely as made up of debts, which can be discharged by money, never mind the situation. His niece throws beer over a friend? He’ll pay for the dry-clean. Keith gets bashed up: take a roll of twenties, what’s your problem?

Carter directly kills four people (and is responsible for several other deaths), all with a blank-eyed lack of reaction. There isn’t any sadism to what he does – the deaths are mostly efficient and to his mind, justified, because by taking actions against his family they disrespected him. When he locks a woman in the boot of his car, and a pair of heavies push the car into the Tyne he doesn’t bat an eyelid at her inevitable death (never mind he slept with her hours before). People who find themselves close to Jack, or drawn into his circle, suffer terribly and he literally couldn’t care less.

Get Carter is the bleakest of all gangster films, shot with an imaginative kitchen-sink beauty by Mike Hodges, which actually carries a lot more visual glory than you might expect. Drained out colours abound – there are virtually no bright primary colours in this, with the whole of Newcastle a mix of muddy browns, soot-stained greys and filthy charcoals. Hodges’ film is also dynamic and fast-paced: he throws in striking aerial and crane shots (there is a beautiful shot that follows a car chase from a bird’s eye view), but also gets down and dirty in this grainy world.

It’s an urgent, lean and mean film constantly kicking you in the shins, but told with skill and artistry. Hodges pieces together a marvellous early scene, where Carter visits local heavy Kinnear (a suave, chillingly well-spoken John Osborne): simultaneously, in one single location, two scenes (both with vital information) play out at the same time – Carter chats to Kinnear’s moll Glenda (Geraldine Moffat), picking up vital information while on the same sofa Kinnear beats his guests at cards. Everything though is perfectly clear: masterful stuff. It’s also a film crammed with small details that reward careful viewing: Carter’s bed has a cross-stitch of “What would Jesus say?” above it (I dread to think) and on his train journey, look out for a fellow passenger with a distinctive ring.

So confidently is this put together, it’s amazing to think Hodges was a first-time director. This is a film dripping with menace, but also a horrifyingly immersive camera. We are frequently thrown into the midst of the action. Carter frequently looms over the camera or is filmed in violent motion moving towards his next goal. There is not a jot of romanticism around the film: neither about the gangsters or the bleak world they operate in. Newcastle is pre-Thatcherite hellhole, with precious little glamour. Even the gangster locales – the clubs and pubs – are bashed-up and unpleasant.

Across the board, the gangsters are exposed as cruel, heartless and vile. Touches of class are ruined by everyone’s fundamental lack of class. Cliff Brumby’s (Brian Mosley) planned classy restaurant sits atop a concrete multi-story car-park. Kinnear’s (John Osborne) fancy country house is the setting of the grimmest, most depressing orgy you’re likely to see. Carter is trying his best to dress classily, but his cruelty always punctures the illusion. He’s introduced watching a porn film with his bosses in London and the film revolves around the seamy underworld of homemade porn.

The women in the film are primarily used by the gangster as props for these films, and Get Carter doesn’t shy away from the exploitative fate for women in this world. However, you can’t disagree that it takes in a bit of exploitation itself. Britt Ekland has high billing for her single scene, where she lies mostly naked on a bed pantily having phone sex with Carter (who goes about this, as all things, with a functional efficiency, at least as interested in the excited reaction of his middle-aged landlady who is sitting in the room with him while he chats on the phone). It’s undeniably a moment for us to gawp but it still feels less cold and cruel than those awful porn films.

Carter discovers his niece has found her way into these. He even sheds a tear over this: but he doesn’t care because of what has happened to her. Again it’s all about him: Carter couldn’t care less about the morals and is perfectly happy for porn to soak up other women. He’s not really that interested in his niece: it’s all about the damage to him, that a “made man” like him should have a member of his family getting boffed like a slag for others entertainment. How bloody dare they?

Get Carter understands this is a dark and soulless world, and is a film bereft of hope. Its hero is a revenge obsessed sociopath, who only smiles in the film after he has burnt everything around him down. Gangsters destroy everything they touch and care about nothing other than themselves. All debts can be settled with money, all women are toys to be used and thrown away. Death means nothing and the world is a drained-out hell of shabby houses and dirty clubs. It’s the grimmest and finest British gangster film out there. Who would want to be gangster after seeing this?