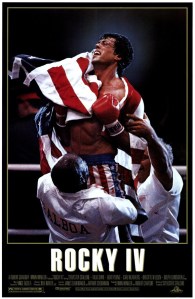

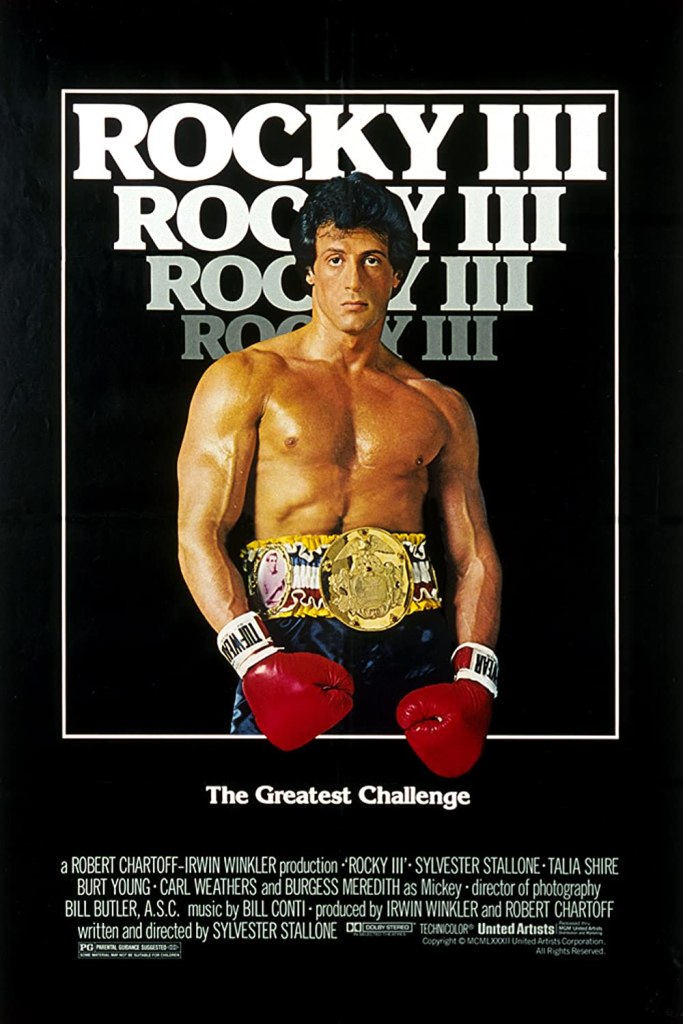

Rocky needs to build his way back to the top – again – in this boxing buddy movie

Director: Sylvester Stallone

Cast: Sylvester Stallone (Rocky Balboa), Talia Shire (Adrian Balboa), Burt Young (Paulie Pennino), Carl Weathers (Apollo Creed), Burgess Meredith (Mickey Goldmill), Tony Burton (Duke Evers), Mr T (Clubber Lang), Hulk Hogan (Thunderlips)

Life is good for Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone)! Ten successful title defences and he is literally on-top of the world. Time to hang up his gloves right? Wrong of course. He’s challenged by hungry new up-and-comer Clubber Lang (Mr T), a brutal, never-beaten machine. Dismissive to all around him, Lang says Rocky has never taken on a proper challenger: turns out he’s right as Mickey (Burgess Meredith) only put Rocky up against challengers he knew he could beat. Lang takes Rocky apart in the fight – not before indirectly causing a fatal heart-attack for Mickey – and Rocky is a broken man. Who else can bring him back from the brink than his old frenemy, the Count of Monte Fisto himself, Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers)?

Rocky III confirms that there are in only so many plots available for a Rocky film. This one shakes the formula up by having Rocky start at the top, then fall to the bottom, then rise back up again. But it’s the same story, now taking place in a slightly different style to the first two. Any sense of kitchen-sink drama is gone from Rocky III. You can see it in the body of Stallone, now a chisselled, Michelangelo sculpture. This is a cartoon with a happy ending, and the fact it’s entertaining doesn’t hide that the whole franchise was leaving reality behind.

Saying that, Rocky III makes a bigger push for tragedy than either of the other two. Stallone leans heavily into incoherent blubbing as Rocky cradles the body of his surrogate father, Mickey dying with one last growling word of wisdom. It’s, of course, the moral of all film mentors that they must eventually kick the bucket so their proteges can take their place. It shakes Rocky up like nothing before. That and the beating he takes from Lang, in a brutal one-sided beat-down.

One of the film’s claim to cult fame is of course the casting of Mr T as Clubber Lang. Growling and scowling like a cartoon heavy, with some punchy one-liners (“I don’t hate Balboa. I pity the fool!”), it’s a part that works due to Mr T’s charisma. Stallone shoots Clubber Lang like some sort of fighting lion, frequently employing slo-mo to focus in on Lang’s scowling face and flying fists, the soundtrack echoing with his roar. Mr T is the series best villain, a man so loathsomely cocky (literally no one likes him, not the crowds, the commentators, his fellow boxers…) that he propositions Adrian, shoves Apollo before the first fight and gives Mickey a heart attack.

You needed someone like that to bring together Apollo and Rocky as a super-team. Rocky III is the series first buddy-movie. It’s hard not to see something faintly homoerotic in Weathers and Stallone, bodies greased and rippling in muscles, eyeing each other up, running along beaches or the faintly sexual air to Weather’s delivery of lines about wanting a “special favour” from Rocky “after the fight”. No wonder there isn’t much time for Adrian in the film – what chance could she have when these two have such a mutual appreciation society going on? – with Talia Shire’s best scene as a sounding board for Rocky’s confession of fear about stepping back into the ring against Lang.

Saying that, the inevitable training sequence – this is the film with the quest for “the Eye of the Tiger” – is great value. It’s fun to watch Rocky pick-up Apollo’s signature Muhammad Ali style quick feet and Weathers is very good as the former champ taking vicarious revenge who forms a genuine friendship with his old rival (I love it when Apollo shadowboxes in excitement when Rocky begins to turn the final fight in his favour). Of course, montage takes Rocky from down-hearted dope (suffering from slo-mo visions which play like a half-arsed panic attack) to freeze-frame triumph. (I’ll also say Rocky III rather neatly mocks Paulie’s kneejerk racism about training with ‘these people’).

To get to these expected beats, Stallone first needed to pad out the run time – and slight plot. Surely that’s the only reason for the bizarre Act One ‘exhibition’ match which sees a complacent Rocky fight an exhibition match against wrestler “Thunderlips” (a terrible cameo from Hulk Hogan), the sort of sequence you keep thinking must be a dream but is in fact real. We also get an initial training montage structured like a modern morality play, Rocky’s lazy prep for fighting Lang sees him living like a Hollywood hotshot, while Lang trains with a monastic dedication. No surprise who is going down in the ring (even if the first fight wasn’t only thirty minutes into the film).

The rematch though doesn’t disappoint, taking its lead from Ali’s rope-a-dope from the Rumble in the Jungle. And the real coda, which is all about friendship, is sweeter than this comic book, Roy of the Rovers film has any right to be. Rocky III replays some of the elements of the first two films, this time as a comic strip, but by focusing on a bromance (and throwing in a properly hissable pantomime villain) despite the fact you know it lacks any inspiration, you’ll still punch the sky when Rocky turns that final fight and leave the film whistling Eye of the Tiger.