Chaplin’s silent swansong, is a funny but quietly impassioned attack on corporate greed

Director: Charles Chaplin

Cast: Charles Chaplin (The factory worker aka The Tramp), Paulette Goddard (The Gamin), Henry Bergman (Café owner), Stanley “Tiny” Sandford (Big Bill), Chester Conklin (Mechanic), Al Ernest Garcia (President of Electro Steel), Stanley Blystone (Gamin’s father), Richard Alexander (Cell mate)

As cinema entered Modern Times of its own, Chaplin had a profound sense that he needed to move with those times. The legendary comedian, whose Tramp persona had made him (possibly) the most famous man in the world, was a silent comedian starting to be left behind by sound. There is a rich relish in the fact that Modern Times, a joke-packed criticism of the coldness of modern industry, is both Chaplin’s last silent and first sound movie, a dipping of the toe in modern times and a valedictory swansong for the past. It’s a film that bridges the ‘modern’ and classic of cinema.

Chaplin is an assembly line-worker eventually driven to a nervous breakdown by the relentless, fast-paced monotony of his work (not to mention a death-defying encounter with the internal workings of the factory machines). Sent to recover in a hospital, he emerges into to find there is little in the world that a dreamer and romantic like him can understand. Again and again, things go wrong. He’s arrested for picking up a red flag in a union march, fired as a night watchman in a department store for helping starving thieves, hopeless as a factory repair man and struggles with tongue-tied silence as a singing waiter. But he and a young ‘Gamin’ (Paulette Goddard), both hope for a better life.

Modern Times has a deceptive structure. It’s easy, at first glance, to see is as four two-reelers thrown together: mini-films in the factory, prison, department store and café. But what Chaplin has created here is a picaresque fable, with the Tramp in the middle. (Only one sequence, with the Tramp as a repairman in a factory, feels superfluous repeating some jokes from the opening act). A morality tale of the modern era, where the big bosses and machines are indifferent to those on the bottom rungs, continually punctuated by the police riding up to bear away the innocent on the slightest pretext. It’s a masterclass of subtle repetition, with moments of contentment forever snatched away.

Chaplin’s most subtly political work became his most controversial. In a way few other films of the 1930s did, Modern Times engages with the conditions and politics of the Great Depression. Housing for the poor is ramshackle, with walls literally held up by mops. The factory alternates exploiting its workers at ever dizzying production speeds with ruthlessly laying them off the moment a slight economic downtown takes place. Union movements are ruthlessly stamped out: when the Tramp accidentally joins a march, he is arrested while the Gamin’s father is shot by police crushing another march. Poverty is ever-present – the Gamin ‘steals’ unwanted food to feed others, laid off factory-workers rob stores for food and when the factories are re-opened there is an almighty struggle from the desperate to get through the gates and claim a few hours of work.

Unsurprisingly Modern Times was condemned as possibly communist and suspiciously anti-American: Chaplin, turning a mirror on conditions in America started to be seen more-and-more by many as a suspicious alien (after all, he’d never taken on American citizenship). Nobody wanted to hear the funnyman turn prophet and many were suspicious of the comedian who used jokes to sweeten the bitter pill (even if, as per many of Chaplin’s messages, it was a rather naïve and simplistic one). It didn’t matter that Modern Times boils down to a plea for a universal love and understanding, it was somehow a creeping sign of the political dangers in ‘modern times’.

Today, distanced from the Red Scare, Modern Times looks far more like what it actually is: a pathos-filled, liberal eye on the working classes that champions the dreamers and the little guys over the corporations and the system. And who better as a hero for that than The Tramp? After all, this was a figure who had struggled against the odds for decades. Modern Times would see that struggle on multiple fronts: against the system, against the machines (literally so, as they swallow him up) and against a way of life that seems to be betting against him.

Even cinema was betting against the Tramp. Chaplin knew he couldn’t put off converting to sound forever. But he also knew the Tramp was a universal figure – and a large part of that was his silence. He never speaks in Modern Times – and when he sings, it’s in garbled, funny-voiced nonsense that effectively keeps him as a universal mute. It’s The Tramp’s final victory lap.

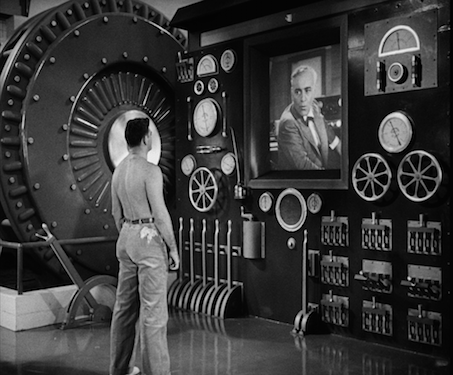

Chaplin’s comic timing remains masterful, and Modern Times is awash with marvellous, balletic set-pieces. Most famous is the opening factory sequence (which owes more than a debt to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and feels remarkably prescient of Orwell’s 1984 with its Big Brotherish boss), a crazed ballet of repetitive, fast-paced movement on the production line – culminating in the legendary sequence of him being sucked into the very gears of the machine. The factory cares so little about the men there, that a machine designed to feed them as they work is dismissed as impractical rather than inhumane – though it gives us a great set piece of Chaplin assaulted by this machine with soup, custard pies and morsels rammed into his face by a mechanical arm.

The comic invention continues through the prison sequence. It’s a sign of the sting under the surface of Modern Times that the highlights of this sequence come about due to the Tramp (accidentally) being high on a mountain of cocaine. Foiling a jail break through coked-up bravado – another wonderfully done sequence, timed to perfection and filmed in one-shot – the Tramp’s reward is not being allowed to stay (and get the roof and food he needs) but early release. (Modern Times finds time, before he goes, for a final pop at ineffectual, superior middle-class do-gooders, lampooning a crusading priest’s wife as coldly distant and the subject of a cheeky gaseous gag).

Modern Times develops into a sweet fairy-tale romance with the introduction of the Gamin. Paulette Goddard gives a radiant performance, full of confidence and comic vibrancy – she becomes the first female lead given near-equal treatment by Chaplin. The department store sequence is grounded with their relationship, from the Gamin taking the opportunity to sleep in a beautifully prepared bed. Their time in the shop at night is full of wonder at the comfort and luxury – that they never see in their own homes – and culminates in a beautifully shot roller-skating sequence, with Chaplin circling balletically on the floors of the shop. (Tellingly though, he does so on the edge of precipice marked danger – Modern Times never forgets that danger lies just round the corner).

It’s the Gamin who lands them a job at a bustling café – awash with spoiled, rich customers – via her dancing ability (there is a fabulously simple transition that sees her pirouetting on the streets to ending the dance in glamourous clothes in the café). Even this moment of happiness is foiled by the law – illogically chasing the Gamin for past vagary offences rather than leaving her to work. But it’s made clear that they are a partnership: fitting the humane message of Modern Times that our best chance of being saved is sticking together.

Modern Times is shot by Chaplin with a striking, sprightly inventiveness. There are signs throughout of Chaplin’s overlooked visual and editorial skill, transitions that are hugely cinematic, storylines that are communicated with maximum efficiency and clarity. As well as the influences of Lang, Chaplin shows a debt to Eisenstein with a striking early visual cut that sees a crowd of sheep (with one black sheep in the middle) cut to a crowd of workers emerging from a subway into the factory. Modern Times pushes its humane message with a gentle persistency, but never lets it dominate the comic and emotional force of the film. Chaplin is an entertainer with a social conscience – but he is an entertainer first of all – and Modern Times is never anything less than charming and funny, even when it is spikey.