Chilling Holocaust film, its unseen horrors only overheard give it supreme power

Director: Jonathan Glazer

Cast: Christian Friedel (Rudolf Höss), Sandra Hüller (Hedwig Höss), Ralph Herforth (Oswald Pohl), Daniel Holzberg (Gerard Maurer), Sascha Maaz (Arthur Liebehenschel), Freya Kreutzkam (Elenore Pohl), Imogen Kogge (Linna Hensel), Johann Karthaus (Klaus Höss), Lilli Falk (Heidetraut Höss), Louis Noah Wite (Hans-Jurgen Höss)

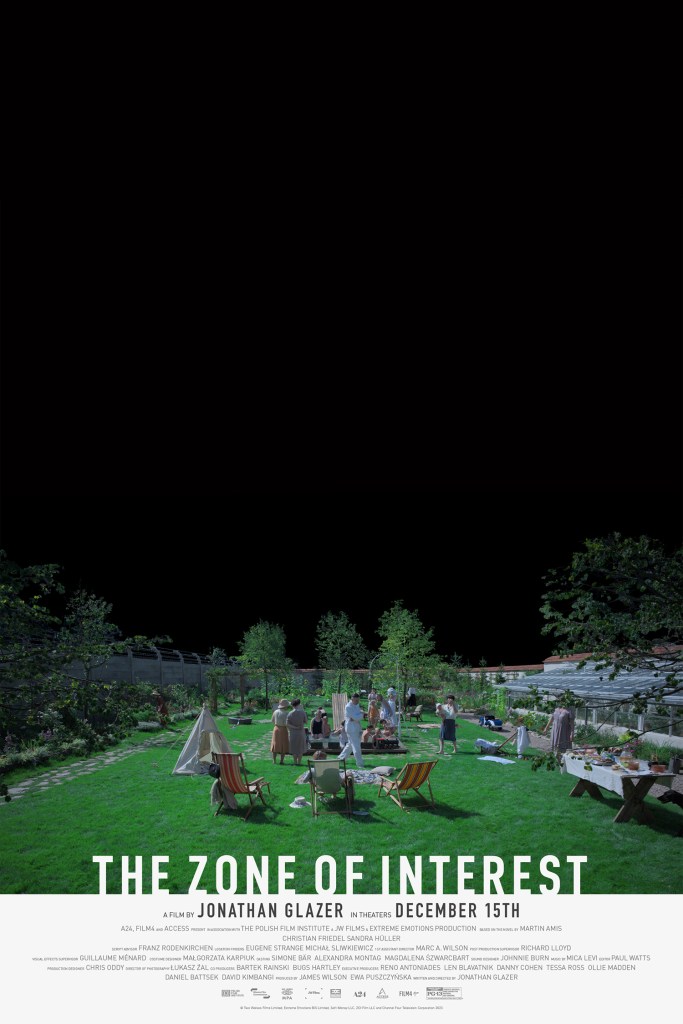

A family enjoys the delights of a summer day beside the river. They laugh, splash each other with water and amble home to their villa, next to where father works. They tune out the all-too-familiar sounds of that workplace to enjoy a family dinner. They are living the dream, out of the city, with a home and beautiful, landscaped garden. The family is Rudolf Höss’. The workplace is Auschwitz. The sounds are of the unimaginable horrors that make their life possible.

Jonathan Glazer’s Holocaust movie is unlike any other ever made. Taking a Martin Amis novel as inspiration, Glazer creates a hauntingly observant film where the plot is simple (Höss works at Auschwitz, the family enjoys a series of everyday events, Höss gets re-posted, his wife remains in their home, Höss later returns to continue his work) but every single frame implies never-seen horrifying events. While the family are indifferent to the distant sounds of trains arriving, industrial churn, gunshots and screams, we can’t be. The only thing that separates the Höss’ heaven of their intricate garden and charming home from the hell of Auschwitz is a single wall.

Glazer’s film never leaves the house for the camp, meaning what we hear is our only clue to what is happening. The Zone of Interest uses sound like almost no other film I’ve seen. Sound designer Johnnie Burns creates an overwhelming soundscape that suggests horrors. The low rumble of industrial sound, the background hum of screams and cracks of gunshot, ignored by the family as white noise. It’s brilliant and sickeningly immersive that never for an instant lets you forget where we are. Glazer complements this with half-seen sights, the most striking the steam of a train arriving visible over the wall of the house, that add to our grim knowledge of what’s happening out of shot.

Glazer lets events play out with a chilling naturalism. Shot on concealed digital cameras with no artificial lighting, there is very little studied here at all. Instead, everything plays out with a terrifyingly low-key sense of reality. Conversations are at times mumbled, movements have a mix of casual and procedural and everything is kept determinedly undramatic. What emerges is the mundane, character-less nature of the Hösses. These people are evil in the sense that the wickedness of their deeds hasn’t even crossed their minds. Two sociopaths who pride themselves on their respectability, presiding over an industrial killing machine.

The film brilliantly balances a lack of overt events with acres of horrific implication. Fishing with his children, Höss steps on a half-seen jaw-bone and suddenly plucks them from the lake, running home with them to practically bleach them clean with the servants left to scrub the bathroom – it’s never stated that human remains are being washed from them, but the look on the face of these servants speaks volumes. (Höss later records a coded memo chastising his team for their lack of care, like a middle manager furious at an untidy storage room.) Hedwig’s mother wakes at night with her room flooded with red light. Opening a curtain to investigate, the camera sees her look of horror, a handkerchief covering her nose, while we only see the faint reflection of flames on the window. Moments like this fill the film, the implications of horrors out of shot.

At its heart, Zone of Interest brings startlingly to life Rudolf Höss, a man who admitted to murdering millions but wanted it known he did not tolerate overt cruelty to his victims. Played with a precise blankness by Christian Friedel, you realise if Hitler had charged him with organising the Reich’s stationary he would have gone about it with the same commitment and passion-free precision as he does mass murder. Does Höss have any idea, deep down, of his vileness? As he carefully, obsessively marches around the house every night shutting off lights and closing doors, is he subconsciously trying to defend his family and shut out reality, bury his knowledge of his evil in household procedure, or is he just as obsessive about this as he is in everything else?

His wife, played with a middle-class, aspirational coldness by Sandra Hüller, seems to have convinced herself she can enjoy all the benefits of the life of an Auschwitz camp commandant, without needing to think seriously about where it comes from. She tries on luscious clothing, brought to her from the camp, and obsessively tends and cares for her garden. Not that it stops her from lashing out at her servants like a petty tyrant. So devoted to her home is she, she refuses to leave it on Höss’ transfer back to Berlin, believing it to be the perfect place to raise her children.

It’s the children that subtly bear the brunt. As the film progresses, the damage to them becomes more and more clear, especially after Höss is reassigned and his attempts to control the environment are ignored by his successor. The daughter who cannot sleep at night, constantly walking the house. The younger son who overhears the forced drowning of a victim and mimics the guard’s cruel authoritarian “humour”. The older son who locks his brother in the greenhouse and mimics the hissing noise of gas. The Höss family are laying the roots to destroy their family in their obsessive desire to build a blinkered perfect home for them.

There is only one note of true kindness in The Zone of Interest. During his research, Glazer discovered a young Polish girl made it her mission to leave fruit at night for the inmates, hidden throughout the camp. Glazer captures this with thermal imaging cameras (eager to maintain his “rule” of no artificial light), giving this girl a sort of mystical, fairy-tale quality (we once even see her while hearing Höss read to his children at night). However, even this act of kindness is corrupted – the forced drowning is caused by a fight over an apple, presumably left by this child.

The Zone of Interest does lose some of its impact when it follows Höss to Berlin – it’s a film that flourishes best as a claustrophobic piece, focused on the house and its grounds. You could argue that The Zone of Interest is effectively a short film, expanded into feature length, making the same point over again. But, on reflection, part of the point is the power of the thudding repetition of that message, the overwhelming impact of people indifferently carrying on in the face of pure evil.

Does Höss realise this on some level? The Zone of Interest concludes with Höss dry-retching on the stairs – he’s such a shell he doesn’t even have enough in him to vomit up – before seeming to stare right out at us into the darkness. Glazer then finally takes us into the camp – to see the museum it is today, quiet, still, tended to with care by the staff. Höss’ life’s work is to create a memorial to his barbarity, where dedicated staff will make sure the picture of evil remains unblemished by dirt. It’s the first-time sound really drains out of the film and it makes for a powerful moment.

The Zone of Interest really lingers with the viewer. Glazer’s subtle and unflashy work builds the film into a powerful experience piece that leaves a lasting impact. It’s a film that grows even more powerful as you unpack the subtleties of its exploration of the banal nature of cruelty and the lasting impact of inhumanity on ourselves and others. A truly unique and important film.