|

Sean Connery plays a Scottish Spaniard and Christopher Lambert a French sounding Scot in cult classic Highlander |

Director: Russell Mulcahy

Cast: Christopher Lambert (Connor MacLeod), Sean Connery (Juan Sanchez-Villalobos Ramirez), Clancy Brown (The Kurgan), Roxanne Hart (Brenda Wyatt), Beatie Edney (Heather MacLeod), Alan North (Lt Frank Morgan), Jon Polito (Detective Walter Bedsoe), Shelia Gish (Rachel Ellenstein)

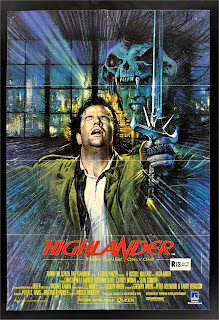

“There can be only one!”. It’s a neat, simple idea and lies at the heart of a cult science-fiction film crammed with them. There is a lot to chuckle at in Highlander. From the air of cheesy cheapness to the Accent Olympics (A Belgian plays a Scot. The world’s most famous Scotsman plays a Spaniard. Brits play Americans. An American plays an Ancient Eastern Barbarian.) But Highlander had huge impact – and was revived countless of times since – because there’s a kind of magic (see what I did there?) to this sci-fi fantasy about immortals struggling over centuries to emerge as the winner of a secret-but-deadly competition. There are so many intriguing ideas and possibilities here, you could make hundreds of adventures in this world (and they have) and still have new areas to explore. The film bombed on its first release in America (look at the poster – is it any wonder? How awful is that?) but it’s had a huge afterlife.

Our hero is Connor MacLeod (Christopher Lambert) who takes part in a lethal sword fight in the car park of Madison Square Gardens in 1985. Turns our Connor was born in the early 1500s, part of a Scottish tribe and was slain by immortal warrior The Kurgan (Clancy Brown). Discovering to his amazement – and his tribe’s horror – that he makes a full recovery from a mortal wound, MacLeod was exiled. He is found and mentored by Ramirez (Sean Connery) who informs him that they are both immortals, destined to join all other immortals in a competition from which there can be only one survivor. The competition will culminate in “The Gathering”, with the winner being given “The Prize”, a mystic power. Turns out 1985’s New York is the scene of the Gathering – and MacLeod and the Kurgan are destined to be the last men standing in the competition.

Perhaps the big thing that makes Highlander such a success is it becomes clear that everyone involved in it seemed to have a whale of a time. Queen were commissioned to write one song for the film: they wrote an album. Mulcahy, Lambert and other members of the cast and crew chipped in their own money to film extra scenes between MacLeod and his adopted daughter. Connery was at his jovial best on the five days he spent filming (Ramirez was to be the only character other than Bond he played twice, in the terrible sequel). All this investment off-camera pays-off in a film frequently rough and ready but also intriguing and enjoyable.

Sure, it’s no masterpiece. It’s very much of its time, with a distinctive 80s vibe and in many ways only scratches the surface of its potential: I’d have loved to see more of MacLeod during the ages, and other Immortals he had interacted with. (We get a confrontation in World War II and a comic duel in Georgian England, where MacLeod repeatedly survives deadly sword thrusts). Our nemesis, the Kurgan, is a frequently overblown and ridiculous character (for all the energy Clancy Brown plays him with) who isn’t quite interesting enough. Lambert is a slightly wooden performer (he learned English for the role – learning it with a Scottish accent was a tough task). Many of the sword fights (with the exception of the final duel) are high-school-play in their hack-and-slash simplicity.

But it doesn’t really matter too much, because Mulcahy shoots the hell out of the picture. Working with a tiny budget, he still manages to give every scene something distinctive to see and an edge in its delivery. The film frequently punches above its weight in its set pieces and with the surprisingly gritty action. Mulcahy has a great eye for the seedy underbelly of New York, just as he does for the Highlands of Scotland. He also handles the romance surprisingly well – both MacLeod’s wife in 16th century Scotland and his love interest in modern New York (including a surprisingly tender love scene) are engaging and complement each other (no mean trick).

Also, the idea is absolute solid gold, and for all that it’s sometimes buried in a cheesy 80s Euro-actioner, Mulcahy still gives the entire thing a sort of mystic force. The tragedy of someone living centuries – watching everyone they love grow old and die around them – is very affectingly done. The different personalities and backgrounds of the immortals are striking and the hints dropped about their involvement in past events intriguing. The concept of immortals growing stronger from beheading other immortals is intriguing and adds a fascinating subtext to every conversation between two of them. The Game itself has an ancient-legend sort of strength, the entire film’s concept having all the revisitable interest of a popular children’s story or a classic slice of mythology.

It looks handsome, and while the actual plot is often predictable and straight-forward, the richness of the backstories and the history carries real impact. Connery is great in a neat cameo – one of his first “mentor” roles (he’s only in it for about 15 minutes, but lifts the entire enterprise with his charisma). The Queen soundtrack is a knockout. Sure, some moments – such as Lambert all too obviously lifted on wires – look as cheap as they probably were, but the entire film is made with a burst of energy and a feeling of enjoyment and love that you have to have a hard heart not to care for it a little bit.