A worthy attempt but a misfire, that frustratingly fails to grapple with deeper feminist issues, settling for a safer, less challenging consensus

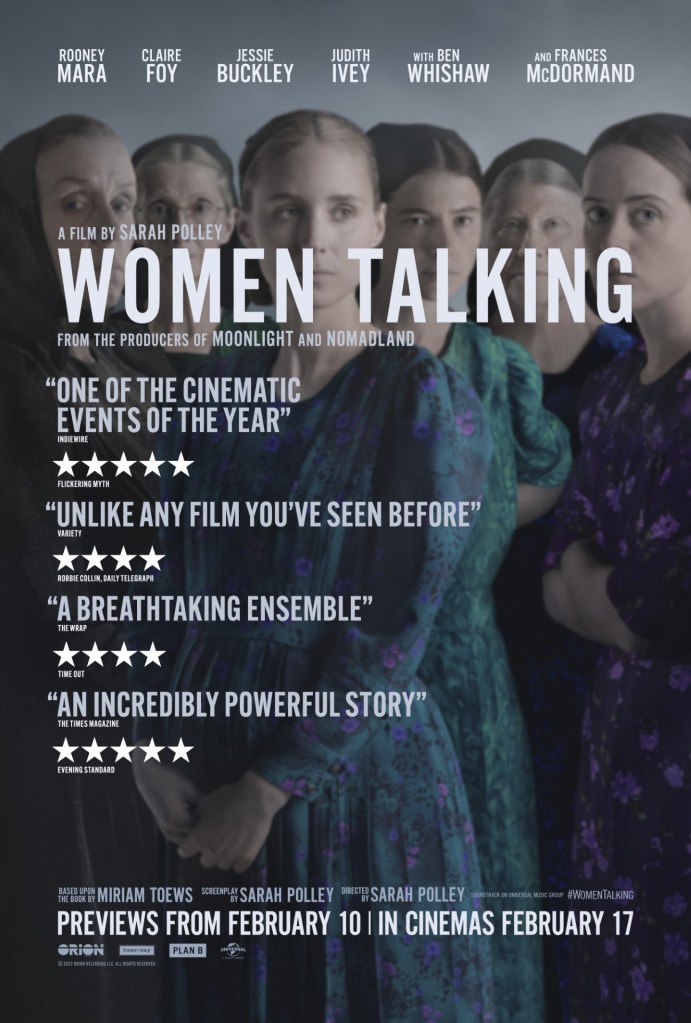

Director: Sarah Polley

Cast: Rooney Mara (Ona), Claire Foy (Salome), Jessie Buckley (Mariche), Judith Ivey (Agata), Ben Whishaw (August), Frances McDormand (Scarface Janz), Shelie McCarthy (Greta), Micelle McLeod Mejal), Kate Hallett (Autje), Liv McNeil (Nietje), Emily Mitchell (Miep), Kira Guloien (Anna)

In 2010, the women of an isolated Mennonite community discover they have been victims of a policy of systemic drugged rape by the men, every night for decades. All this remains unknown until a man is caught in the act and the attackers arrested. The other men go to the city to bail them out, informing the women they will be expected to forgive on their return. The women hold a vote about what to do: do nothing, stay and fight or leave. When the vote is tied between the latter two options, the women decide the final choice will be in the hands of a small group of their number, who will debate in the community’s hay loft.

All of this happens, in voiceover, in the film’s opening few minutes. It all sounds more engaging, challenging and dynamic than what actually happens in the film. I saw Women Talking with my wife, who is passionate about the issues this film wants to deal with. We were both united in our view of the film: Women Talking is full of talking, but no one really says anything. It’s a missed opportunity that fails to convert its undeniably powerful premise – or the committed and passionate performances of its cast – into something that really successfully grapples with, and comments on, the issues, with a cast of characters who feel more like devices than fully-rounded people discovering their voices and freedom.

It’s a film that should have the urgency of a time-bound debate and the passion of a group of women discovering that they have the power to make decisions themselves. But the film feels slow (much longer than its two hours), flat and theoretical where it should be filled with debate and different ideas. It has moments of power and speeches of tragedy, but it doesn’t manage to make this something truly revolutionary.

The film would have been more interesting if it had been about everything covered in that opening monologue. In this community the women are kept illiterate, have never been allowed to be part of any decision-making and are so oppressed they don’t even have language to understand what sexual assault is. There was a fascinating film waiting to be made about these women working out exactly what had happened to them – imagine the heart-rending conversations that must have involved – and discovering they were just as capable of reaching decisions in their own right as men. Of finding their voice and freedom.

Now that is a film about feminism I want to see! I wanted to see these women who have never even considered ideas about independence and self-determination discovering they could do that. Just having a vote in a community like this one is an astonishing revolutionary act – it shouldn’t be so blandly passed over as this film does. How did these women even realise that they could decide for themselves what they to do with their lives?

Instead, we get a film where actual debate is surprisingly neutered. Frances McDormand’s character is the voice of conservatism, but walks out of the debate after five minutes and never comes back. With her gone, no counter-arguments are raised, no voice given to help understand why people (and many of them have done so) would choose to stay in relationships even after they know the truth. McDormand’s character is almost certainly wrong – the women should get out of this awful place – but we should at least hear her say why she wants to stay and the film should trust us to understand that listening to her viewpoint isn’t the same as agreeing with it.

In fact, it would have been fascinating to hear why so many women in the community heard about the systemic rape and yet voted to stay. The hay-loft debates should hum with the exchange of ideas. We should hear different viewpoints. Many people voted to stay and do nothing: why? Let’s hear what makes these women accept what’s happened to them. Are they institutionalised, love their husbands despite their faults or can’t imagine leaving their homes no matter the cost? We don’t know. It’s like the film makers were worried that a debate which actually included all potential viewpoints would have been seen as reducing the horror. In reality, however, it’s essential.

There is also a fascinating discussion to engage with about justice and forgiveness – particularly given the film’s setting in a religious community that preaches forgiveness. The men have demanded the women forgive. Ona (Rooney Mara) declares early on that forced forgiveness cannot be real. But instead of engaging with this, that throwaway is all we get. It’s a deep question which we often grapple with in the wake of terrible crimes. Whole books have been devoted to people who can or cannot forgive those who’ve committed terrible crimes against them or their loved ones. There’s so much this film could have delved into with its cast of women who’ve been told all their lives they must forgive – but it had no interest.

Instead, the film wants to make things easy. It completely shirks any debate of religion. This is a community of women whose entire understanding of the world is founded on the Bible and religious instruction. But yet God, faith and Christian ideas barely come up. It’s briefly mentioned that leaving the community means exile from heaven – but that is benched and never raised again. It should be at the heart of their considerations. There isn’t even a debate about whether their community’s teachings are legitimate (since they are partly based on systemic rape, we can guess not).

In the end rather than really tackling themes, we get conversations which do little but make the same point over and over again. Some of these speeches are undeniably powerful, and the performances of Foy and Buckley in particular are strong, but they are weakened by the lack of depth to the characters.

Women Talking is full of words but never says as much as you are desperate for it to do. The actors do a fine job with the passionate speeches and bring a lot of power to this chamber piece. But it’s frustrating that we feel robbed of seeing these women realise they have the power to choose and instead circles a highly emotive but ultimately slightly unrevealing discussion intercut with on-the-nose shots of fields, playing children and empty kitchen tables. It manages to avoid focusing on anything potentially interesting or engaging and feels like a worthy missed opportunity.