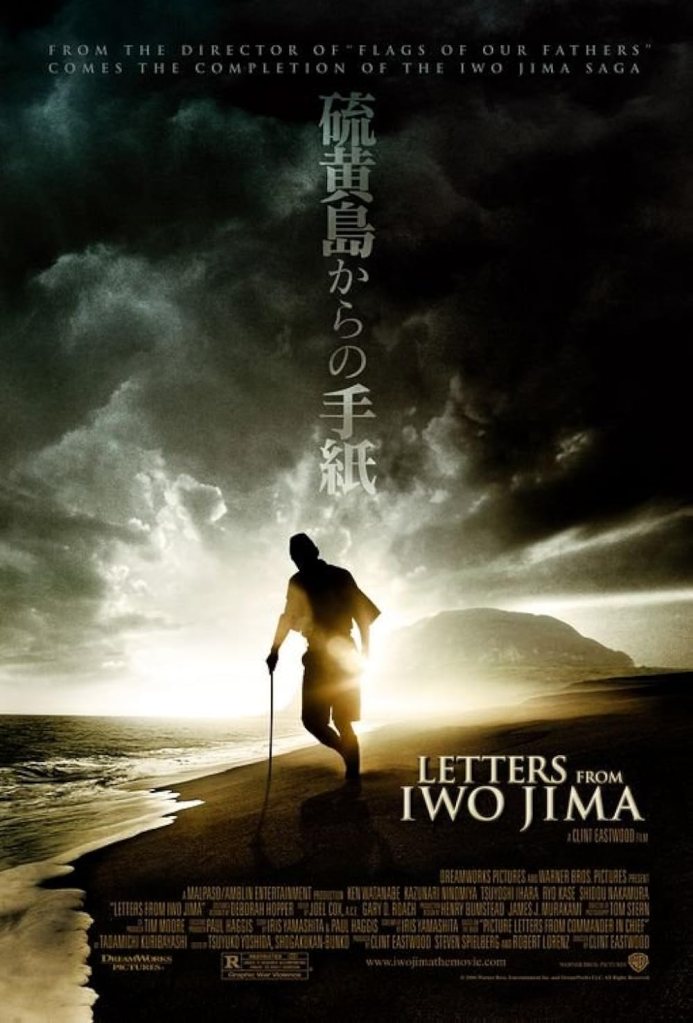

Thoughtful, sensitive, respectful and insightful war-movie – one of Eastwood’s best

Director: Clint Eastwood

Cast: Ken Watanabe (General Tadamichi Kuribayashi), Kazunari Ninomiya Private Saigo), Tsuyoshi Ihara (Lt Colonel Baron Takeichi Nishi), Ryō Kase (Private Shimizu), Shidō Nakamura (Lt Ito), Hiroshi Watanabe (Lt Fujita), Takumi Bando (Captain Tanida), Yuki Matsuzaki (Private Nozaki), Takashi Yamaguchi (Private Kashiwara), Eijiro Ozaki (Lt Okubo)

Eastwood’s original plan for his Iwo Jima epic was to tell the story from both perspectives, like a sort of Tora, Tora, Tora on the beaches. But, as the amount of story expanded and expanded, he decided to make two films (it helps being a Hollywood Legend when you change your mind like this). The American story would be covered in the melancholic-but-traditional Flags of Our Fathers, focusing on the soldiers who rose that famous flag on the peak of Mount Suribachi. For the Japanese story, Eastwood would do something more daring: tell the story in Japanese, entirely from their perspective presenting their military culture not as wicked or misguided but as a legitimate mantra as prone to extremes as the American one.

Letters From Iwo Jima is equally melancholic as its partner film, helped by its elegiac music score from Michael Stevens and Kyle Eastwood. It’s shot in a coldly austere, sepia-toned monochrome – there is barely any colour in it – and large chunks of it play out in gloomy subterranean quietness where the only sound of war is the artillery ground-pounding above the entrenched Japanese soldiers. This is the apogee of Eastwood’s moody, restrained style – perhaps he recognised and admired the reserve and formality in Japanese culture. Letters From Iwo Jima seems at first unfussy and objective so it’s a surprise how affecting and humane it becomes, all while seeing the virtues and deep flaws in a military system where the individual mattered a lot less than the whole.

Iwo Jima was a brutal fight to the death over an island less than 12 mi2, a grey rock in the Pacific that’s only value was as an air strip for launching bombing raids on mainland Japan. Over 110,000 American soldiers took on 20,000 Japanese defenders in a campaign expected to last just a few days, but dragged out over a punishing 36. The relentless Japanese defence resulted in over 25,000 American casualties and c. 90% fatalities for the Japanese. Letters From Iwo Jima explores the mentality of an army that almost completely accepted (from commanding officers down to junior privates) their destiny, no their duty, was to not survive the island’s defence.

The defence’s success is due to the skilled command of General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, a remarkable, restrained performance of relentless determination mixed with deep humanity from Ken Watanabe (unfairly snubbed at the Oscars). Kuribayashi over-rules his senior officers desire for a bayonet charge against the overwhelming American landing forces on the beaches. He knows this traditional attack would lead to suicidal instant defeat for the out-numbered, out-gunned Japanese. Instead Kuribayashi orders a tunnel network built across the island, to allow hit-and-run attacks designed to inflict maximum casualties. Rather than committing suicide at their posts on defeat, soldiers were ordered to withdraw from indefensible positions to continue the fight for as long as possible.

This strategic defence-in-depth strategy is denounced by several of his senior officers as either defeatism or American-sympathy. Kuribayashi knows victory is impossible – he arrives on the island writing a letter to his wife stating he will not live to see her again. But he also knows his tactic is the only way to slow down the American juggernaut. In his opinion, protecting Japan from air attack for a few more weeks is worth sacrificing his and all the lives of the 20,000 men under his command.

Kuribayashi respects Americans – flashbacks show his happiness in the 30s as a military liaison in California, his easy friendships with American officers and desire for co-operation with the USA. But in the same scene he unquestioningly (though with a warm smile) says he will serve his country no matter what. He’s a man of principle and honour, and even if he doesn’t agree with the war, he is for Japan right-or-wrong and will not think twice about giving his life in its service. This attitude soaks through the Japanese soldiers, and Letters From Iwo Jima presents it largely without moral judgement. There are shocking moments where defeated soldiers in Suribachi, weep as they looks at photos of their loved ones while clasping live grenades to their chest so that they may die at their post rather than live with the shame of failing their country. But, the film subtly asks, how different is this from the self-sacrifice countless American war films have (rightly) praised in their soldiers?

The difference is cultural. Very few American soldiers would choose suicide in a cave rather than the thought of confronting their families as defeated men. For Japanese soldiers, this is the ultimate strength, a view shared not just by incompetent, trigger-happy bullies like Captain Ito but right up to Kuribayashi himself who never considers for a moment surrender and living, choosing a suicidal night attack with his last soldiers and suicide on the last piece of earth on Iwo Jima that could still be just about considered Japanese. That’s an institutional expectation of total self-sacrifice, even when the sacrifice is completely symbolic, that has no real comparison in Western militaries.

The soldiers – as we hear in their letters, read to us in voiceover – love their families and they relate to a wounded GI from Oklahoma who talks about his mother (a slightly twee moment in another wise subtle film), but they also believe that the whole (Japan) is far more important than the individual (themselves). Trees should always be sacrificed to slow the fire and protect the forest. Letters From Iwo Jima may show the dangerous excesses this produces in the most fanatical, but doesn’t denounce this extreme penchant for sacrifice or give a clumsy moment of realisation that it is inherently ‘wrong’. Neither does it present Western, individual ideals as superior (indeed the few American soldiers seen are a mixed bag, as much prone to vengeful violence as their opponents).

Letters From Iwo Jima follows Private Saigo (very well played with a bewildered sense of fear and growing desire to live by Kazunari Ninomiya), the character closest to acting as a criticism of the Japanese mindset. A baker, who wants to see his wife and new-born child, he doesn’t really want to die on the island, but never questions it is his duty to do so. And his objections to suicidal orders or kamikaze attacks isn’t grounded in their senselessness but that they run contrary to Kuribayashi’s wider orders. Even our most relatable (to Western eyes) character, one who eventually accepts the idea of surrender when all is lost, is still part of the same culture where placing your own needs and desires before the whole is considered deeply shameful.

Perhaps this thoughtful, non-judgemental exploration of Japanese culture is why Letters From Iwo Jima (unusually for American war films) did very strong business in Japan. Unlike the eventual death cult of Nazism (see the exceptional Downfall), where suicide came from bitter pride and fear, here it’s the ultimate, terrible-but-logical outcome for a mentality that turned a small island into a respected world power. It’s not presented as a freakish aberration or some sort of national genetic character flaw: it’s in many ways a sort of perverse nobility which has, like all noble systems, advocates who are broad-minded and empathetic and those who are prejudiced and fanatical. Letters From Iwo Jima’s strength is it never presents it as inherently evil, rather a choice with good and bad outcomes.

Eastwood’s superbly directed film, perhaps one of his finest, is full of such thoughtful, unjudgmental reflections on duty and service and what loyalties to something larger than ourselves drive us to do. Shot with an austere, haunting chill and superbly played by a faultless cast, Letters From Iwo Jima is an earnest, mature piece of work and a quite extraordinarily unique war film.