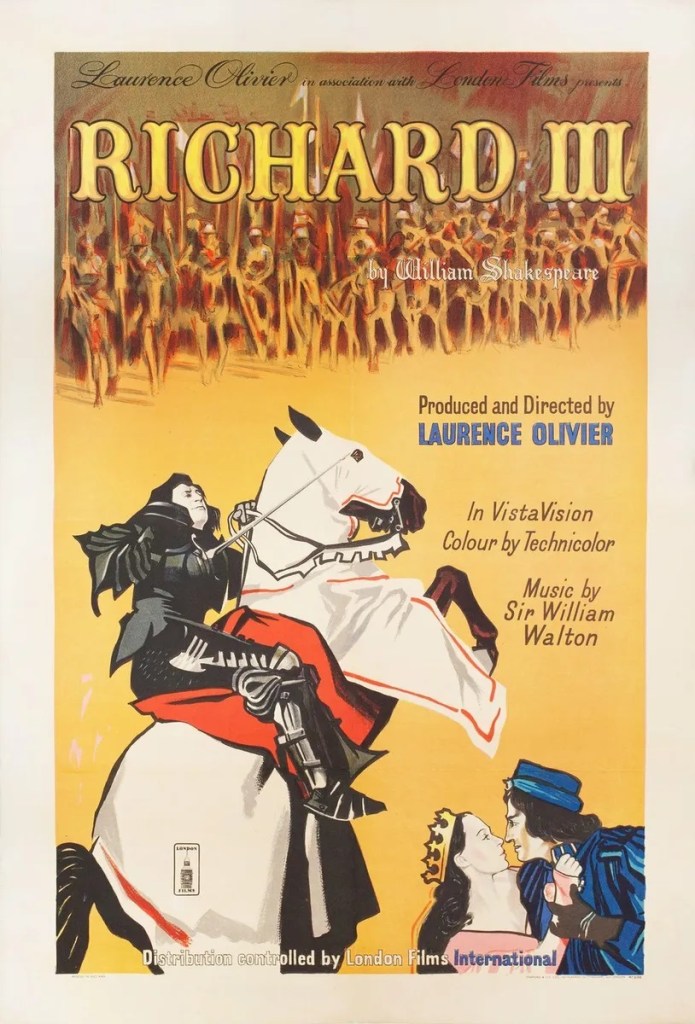

Olivier stamps his claim to Shakespeare’s greatest villain in this gorgeous theatrical epic

Director: Laurence Olivier

Cast: Laurence Olivier (Richard III), Cedric Hardwicke (Edward IV), John Gielgud (Clarence), Ralph Richardson (Buckingham), Claire Bloom (Lady Anne), Helen Haye (Duchess of York), Pamela Brown (Mistress Shore), Alec Clunes (Lord Hastings), Laurence Naismith (Lord Stanley), Norman Wooland (Catesby), Clive Morton (Lord Rivers), Douglas Wilmer (Dorset), Stanley Baker (Richmond), Mary Kerridge (Queen Elizabeth), Esmond Knight (Ratcliffe), John Laurie (Lovell), Patrick Troughton (Sir James Tyrell), Michael Gough (Murderer)

Olivier had played the greatest Shakespeare hero in Henry V and made Hamlet the most romantic princes of film. Having scaled those heights, did he also want to set the benchmark for Shakespearean villainy? Perhaps, with his vaulting ambition and competitiveness, he knew his clipped, precise tones and physical suppleness was perhaps best suited to playing the villain. What better role to prove it than the “poisonous, bunch-backed toad” himself, Richard III. Olivier bought to the screen a performance that would be as influential as his Hamlet (perhaps even more so), an embodiment of the role that all future Richards would be compared to.

I like to think of Richard IIII as a twisted inversion of Henry V. Like that film, the action is shot in lusciously beautiful technicolour, with beautiful costumes and a marvellously stirring, magnetic score by William Walton. It has courtly intrigues, a charismatic lead, the seduction of a young princess, many of the same actors and caps itself in a bravura battle shot on location. The only difference being that, instead of “the mirror of all Christian kings”, our lead is a twisted, remorseless killer who acts as his own Chorus to bring us on-side with his Machiavellian schemes. (There is a fun little opening message, stressing that this is a legend not the truth, that almost feels like an apology in advance to the Ricardian societies of today).

Olivier’s performance is the heart and soul of this film, and it’s possibly his finest cinematic (and certainly his finest screen Shakespeare) role. This Richard is openly – almost proudly – cruel and hypocritical, sociopathic in his amoral ease with the death and slaughter of his nearest and dearest (including his beloved wife, brother and nephews to whom he is sweetness and charm), overwhelmingly impressed with his own cunning and eagerly inviting us to share in his villainy. Olivier practically caresses the camera in his readiness to get close to us, forever turning towards it with a smile, quick aside or delighted breakdown of schemes to come. Olivier inverts his matinee idol looks into a stooped smugness (his costume, with its dangling sleeves, frequently makes him look like a spider) and his clipped vocal precision is dialled up to stress his heartless self-confidence.

Stare into Richard’s eyes and all we see is an uncaring blankness, the chill of a man who cares for nobody except himself. His sigil maybe a boar, but he resembles a wolf, devouring the Lords around him. Much of the first two thirds sees him keep a steady illusion of outward good fellowship. He comforts Gielgud’s Clarence with genuine care, greets Hastings like an old friend, is mortified and hurt by the suspicions cast on him by the Queen and her family, smiles with affection at his cousins. It means the moments where Olivier lets the mask slip even more shocking: the matter-of-fact abruptness he urges murderers not to take pity on Clarence, the whipped glare of pure loathing he shoots at the princes after an ill-advised joke about his hunched back or the imperious hand he shoots at Buckingham to kiss after being acclaimed by the crowds, harshly establishing the hierarchical nature of their ‘friendship’.

While the charisma of course is natural to a performer as magnetically assuring as Olivier – and this Richard is truly, outrageously, wicked in his charm – he also nails the moments of weakness. Having achieved the crown, Olivier allows not a moment of enjoyment of his feat, but his brow furrows into barely suppressed concern and anxiety that he may be removed by schemes exactly like his own. The threat of armies marching on him sees him first lose his temper publicly and then leap to cradle the throne in his arms like a possessive child. The morning of Bosworth, he even seems quietly shocked at the very idea that he could feel fear.

Richard III, despite its length, makes substantial cuts to the original play, including throwing in elements from Henry VI. Several characters – most notably Queen Margaret, whose major confrontation scene with Richard is lost altogether – are cut or removed all together. Olivier reshuffles the order of events, most notably shifting the arrest of Clarence to split up the seduction of Lady Anne. Richard’s late speech of remorse before the battle of Bosworth hits the cutting-room floor (Olivier’s Richard never seems like a man even remotely capable of being sorry for his deeds). Several small additions from the 18th century by Colley Cibber and David Garrick are kept in (most noticeably his whisper to his horse on the eve of battle that “Richard’s himself again”).

The film is deliberately shot with a sense of theatrical realism to it, Olivier favouring long takes so as to showcase the Shakespearean ease of the cast (much was made of the cast containing all four of the Great Theatrical Knights of the time in Olivier, Richardson, Gielgud and Hardwicke). The camera frequently roams and moves, most strikingly during the film’s first monologue from Olivier, where it flows from the coronation retinue outside the throne room, through a door, to find Richard himself waiting for us in the hall. It’s set is similarly theatrical, a sprawling interconnected building (with some very obvious painted backdrops) where the Palace of Westminster, the Tower of London and Westminster Abbey seem to be one massively interconnected building.

The film makes superb use of shadows, the camera frequently panning from our characters (especially Richard) to see their shadows stretch across floors and up walls. The claustrophobia of the interconnected set also helps here, making events seem incredibly telescoped (it feels like the film takes place in just a few days at most). It makes the court feel like a nightmare world completely under the control of Richard, who knows every corner to turn and can seemingly be in several different places at once. In that sense, filming Bosworth outside on location in Spain seems like a neat metaphor for Richard’s lack of control of events: suddenly he’s in a sprawling open field, where it’s possible to get lost and it takes genuine time to get from A to B.

Olivier may dominate the film with a performance of stunningly charismatic vileness, but he has assembled a superb cast. Ralph Richardson is superb as a supple, sly Buckingham, a medieval spin doctor whose ambitious amorality only goes so far. While I find Gielgud’s delivery of Clarence’s dream speech a little too poetic, there are strong performances from reliable players like Laurence Naismith’s uncomfortable Stanley and Norman Wooland’s arrogant Catesby while Stanley Baker makes a highly effective debut as a matinee idol Richmond. Claire Bloom superbly plays both Lady Anne’s fragility but also a dark sexual attraction she barely understands for this monster. Perhaps most striking though is Pamela Brown’s wordless performance as Mistress Shore (mistress first to Edward IV then Hastings), a character referred to in the play but here turned into a sultry, seductive figure who moves as easily (and untraceably) around the locations as Richard does.

Fittingly for a film obsessed with the quest for power, we return again and again to the image of the crown. It fills the first real shot of the film, bookmarking its beginning and end and frequently returns to fill the frame at key moments. With the films gorgeous cinematography, it’s a tour-de-force for its director-star and a strikingly influential landmark in ‘traditional’ Shakespeare film-making.