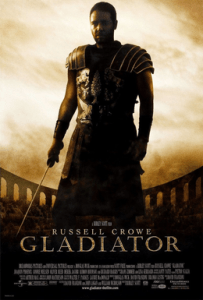

Gonzo sequel sits firmly in the shadow of the illustrious predecessor it tries to imitate time and time again

Director: Ridley Scott

Cast: Paul Mescal (Lucius Verus/Hanno), Pedro Pascal (Marcus Acacius), Connie Nielsen (Lucilla), Denzel Washington (Macrinus), Joseph Quinn (Emperor Geta), Fred Hechinger (Emperor Caracalla), Derek Jacobi (Gracchus), Tim McInnerny (Thraex), Alexander Karim (Ravi), Peter Mensah (Jubartha), Lior Raz (Viggo), Matt Lucas (Master of Ceremonies), Rory McGann (Tegula)

There’s nothing particularly wrong with Gladiator II. In many ways, it’s a big, silly, perfectly inoffensive swords-and-sandals flick, with the violence dialled up. But as a sequel to Gladiator – a film that married scale with a hugely relatable emotional story about one man’s quest to avenge his family and unite with them in the afterlife – it’s not even in the same league. Gladiator II’s biggest problem is that when it tries to do something different from Gladiator it usually fails and when it hues close to the original, it only reminds you what a good film that was and how you’d honestly much rather watch that again.

Gladiator II picks up 16 years after the first film. The nephew of the late Commodus, Lucius (Paul Mescal) lives with his wife in the last free city of Numidia. That ends when the city is taken by a Roman army, under the command of General Marcus Acacius (Pedro Pascal) and Lucius’ wife is killed. Lucius, taken as a slave, of course arrives in Rome and becomes a gladiator in the service of the ambitious, unscrupulous wheeler-dealer Macrinus (Denzel Washington). Macrinus has schemes to exploit the fragile Empire, ruled by brothers Geta (Joseph Quinn) and Caracalla (Fred Hechinger). General Acacius and his wife, Lucius’ mother Lucilla (Connie Nielsen), also plan to overthrow the Emperors. And Lucius also plans revenge against Acacius and all of Rome in that order.

Gladiator II is awash in echoes from the first film. It gives Lucius mostly the same motivation as Maximus. It opens with a big Roman battle. It rushes to get Lucius back into the Colosseum, via a few reluctant bouts in the provinces. He is accepted as a leader by the other gladiators, marshalling them like troops. Connie Nielsen gets the same plot and versions of the same “visiting the hero in prison” scenes. There is a lot of talk about the power of the mob. Hands are frequently rubbed in the dirt. The famous quotes (“Strength and honour!”) are paraded out. Lucius cos-plays as Maximus for the film’s big ending. The final scene shows a survivor searching in the dirt of the Colosseum. Just when you think the film has at least not shown us a shot of a hand stroking some wheat… Gladiator II even chucks that in. It’s a big bit of nostalgia IP dressed up as homage.

But Gladiator II only seems to understand the surface elements of what made the first film successful – not the heart. Gladiator was a very simple story: it was a film about a man who deeply loved his late wife and son, determined to carry on living until he avenged them. Sure there were plot mechanics about the future of the Empire and “The Dream of Rome” – but this was window dressing to a plot focused on very real emotions, about caring for your loved ones. Maximus was carefully crafted as an honourable, decent man, a reluctant warrior who fought because he must. This narrative simplicity is completely lost in Gladiator II, a film so awash with subplots, schemes and shady deals that it becomes hard to follow – and eventually to care – who is on whose side and why.

There are at least four competing schemes at play in Gladiator II, each fighting for screen time like rats in a trap. It’s at best a bloody stalemate. The character who emerges best from all this is Macrinus. Based on the first Moorish Emperor of Rome (a fascinating, if short-lived, figure) he’s played with a meme-courting bombast by a clearly having-fun Denzel Washington (his rolling pronunciation of the word “Pol-leetic-sah!” designed to launch a thousand GIFs). A flamboyant figure, he effectively mixes elements of both Proximo and Commodus from the first film with the larger-than-life amorality of Washington’s Alonzo Harris (if Harris was a slightly camp Roman aristocrat). Most of the film’s enjoyable moments revolve around his increasingly brazen manipulations, first of a corrupt senator (an enjoyably sleazy Tim McInnerny) then the two deranged and incompetent Emperors. Every other plotline eventually falls into the shadow of Washington’s scenery-chewing excess (by the time Macrinus is using a character’s severed head as a prop to intimidate the Senate, you realise you just have to go with it).

Gladiator II though needs to split its focus between these multitudinal plot lines, to the detriment of all of them. The emperors fiddle and feud while Rome burns. Various soldiers and senators line-up familiar plots to restore the republic. Lucius, the character we are supposed to relate to the most, is the one who starts to lose our interest. Paul Mescal does an effective job as this growling, surly figure, even if he doesn’t quite have the force to pull off his final late-act speeches. But the film rushes his elevation to leader among the gladiators so quickly it feels unearned – as well as stuffing the film with a multitude of sidekicks so anonymous they blur into one, so much so you won’t even notice (or care) when they start to bite the big one.

On top of which, Lucius zigs-zags through motivations with all the logic of a charging rhino. He goes from wishing he was dead, to fighting desperately for life, to vowing revenge on one man to suddenly changing his mind, to leading a proto-Spartacus inspired revolt to ditching the idea, to denouncing his mother and birth-right until suddenly he doesn’t, to half-heartedly resenting Macrinus to announcing he only lives to see him die, from rejecting Maximus to cos-playing him – how are we supposed to keep up with this? The fact he’s a man of very little words doesn’t help.

When he does speak it’s never particularly punchy. Scarpia’s workman-like dialogue gives him a clumsy rallying cry – “Where we are not where death is. Where death is, we are not” – which manages to be both leaden word-soup and spectacularly unrallying. The film recognises this by having Lucius ditch it late on for a rousing cry of – what else? – “Strength and honour”. Scarpia’s script, along with its muddy plotting, is full of deathly, forgettable pap; as well as riffing so determinedly on Gladiator that you’d think not a day went by in the bowels of the Colosseum without a wistful discussion about Maximus. Gladiator II also manages to pee across several ideas at the heart of Gladiator, from the potential implication that Maximus may have cheated on his wife to father Lucius (even Russell Crowe questioned that one) to the idea that at the end of the film they buried him in the Colosseum, which seems like the last thing they’d do.

In fact, I started to think that Ridley Scott’s main motivation for doing Gladiator II was to chuck in all the gonzo ideas he couldn’t make work (or find the budget for) in the first film. A fight with a mad rhino. A flooded arena full of ships (with added sharks – how these were caught and conveyed in-land to the arena just doesn’t even bear thinking about). Lucius and his fellow prisoners take on man-eating poorly-CGI’d baboons (Lucius’ position as leader largely stems from him biting one of these beasts before strangling it to death). Outside the arena, heads, hands and arms are hacked off and Scott effectively opens the film with a re-stage of the battle of Jerusalem from Kingdom of Heaven – only the siege towers this time are on ships charging the sea walls.

All of this is pretty well done, don’t get me wrong. Scott can do historical epic on screen like few others. But Gladiator II actually suggests that where he lucked out on Gladiator was keeping it simple with a strong story. Gladiator II feels something where attention has been lavished on the scale and the bombast, but that plot and character have been rushed. The film is about 15 minutes shorter than Gladiator while telling a story twice as complex, a mixture that doesn’t work well. In fact, the main feeling I had coming out from it was that I didn’t need to see it again and if I could re-watch Gladiator and pretend this didn’t exist at all, I might be a happier man. Gladiator II lives so absolutely in the shadow of its predecessor, that its flaws become more apparent through the constant invitation the viewer is made to compare and contrast them. This one won’t echo to 2030 let alone eternity.