|

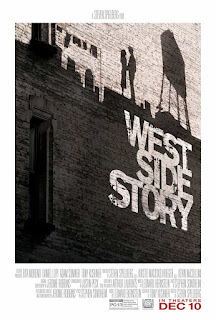

Ansel Elgort and Rachel Zegler are star cross’d lovers in Spielberg’s triumphant West Side Story |

Director: Steven Spielberg

Cast: Ansel Elgort (Tony), Rachel Zegler (Maria), Ariana DeBose (Antia), David Alvarez (Bernardo), Mike Faist (Riff), Rita Moreno (Valentina), Brian d’Arcy James (Officer Krupke), Corey Stoll (Lt Schrank), Josh Andres Rivera (Chino), Iris Menas (Anybodys)

Was there actually a need to remake West Side Story? It’s the question everyone was asking before the film’s release. Judging by the disaster at the Box Office (also connected to our old friend Covid), it’s a question people are still asking. Well, you remake it by refocusing and partially reinventing it while remaining loyal to the roots of what makes this one of the greatest 20th century musicals. Spielberg’s triumphant film does exactly this, in many places even exceeding the Oscar winning original. This West Side Story is full of toe-tapping, heart-breaking numbers, gloriously choreographed numbers and scenes of high emotion and social insight.

In 1957 in Manhattan’s West Side, it’s the dying days of the San Juan Hill district, which is being slowly bulldozed to build the Lincoln Centre. Scrambling to retain control of what’s left are two gangs of youths: the Jets, a group of white rough kids led by Riff (Mike Faist) and the Sharks, a migrant Puerto Rican gang led by would-be boxer Bernardo (David Alvarez). The two groups plan a ‘rumble’ to settle matters forever. A fight that ends up carrying even more importance when both communities are outraged by the burgeoning romance between former Jet leader Tony (Ansel Elgort) and Bernardo’s sister Maria (Rachel Zegler). Will love triumph over hate? Well, it’s based on Romeo and Juliet, so I’ll leave it to you to work that out.

The original, Oscar-laden, West Side Story is a ground-breaking and brilliant musical. Based closely on the triumphant original Broadway production, it showcased earth-shatteringly brilliant choreography by Jerome Robbins. The sort of grace, power, passion and beauty in movement that very few productions of anything have got anywhere near matching. Spielberg’s remake can’t match that – and wisely doesn’t try, rejigging and reinventing the choreography with touches of inspiration from Robbins’ work. But, in many ways, it matches and even surpasses the other elements of the original.

The musical’s book is radically re-worked by playwright Tony Kurshner to stress the racial and social clashes between these two very different communities. Helped as well by the racially accurate casting (memories of Natalie Wood passing herself off as Puerto Rican are quickly dispatched), Spielberg’s film transforms West Side Story into a film exposing the kneejerk jingoism and xenophobia of the Jets (who are often deeply unlikeable) and the touchy, insecure defensiveness of the Puerto Rican Sharks.

Everything in the film works to establish the difficulty the Pueto Rican community had in settling in America. From language problems – most of the characters are still mastering English, with Spanish exchanges untranslated – to the obvious bias of police officers like Corey Stoll’s bullying Lt Schrank (officers and others frequently order the Puerto Ricans to “speak English”). Maria and Anita no longer work in a dress shop, but as cleaners in a department store. Racial slurs pepper the dialogue (Spic and Gringo litter the dialogue). The Jets are first seen defacing a mural of a Pueto Rican flag. Loyalty to your community – both of whom see themselves as under siege – is more important than anything. The film bubbles with an awareness of time, place and the dangers and troubles faced by migrant communities far more than the original.

For that choreography, Justin Peck keeps the inspiration of Robbins, but mixes it with his own fast-paced, electric dynamism. The big numbers dominate the screen, from opening confrontation of the Jets and Sharks to the carnivalesque America, the playful Office Krupke, the frentic Gym Dance and the ballet inspired Cool. The choreography is earthier and punchier (in some cases literally so) more than Robbins, with a rough and tumble physicality and strenuous attack that contrasts with the balletic perfection of the original. It’s both a tribute to the original and also very much its own thing – and works perfectly.

Balancing tribute and forging its new identity is also at the heart of Spielberg’s brilliant direction. He’s confident enough to shoot many of the musical numbers with a Hollywood classic style – which allows us to see and admire all the choreography. But he also mixes this with sweeping, immersive camera work, thrilling tracking shots and beautiful images – there is a great one of Tony standing in a puddle surrounded with apartment window reflections, which looks like he’s surrounded with stars. Spielberg brings the demolished buildings very much into the visual design, part of making this West Side Story, earthier and rougher. The film is electrically paced and lensed with an expert eye.

The film’s two leads are both superior to the originals. Ansel Elgort is a fine singer (with a heartfelt rendition of Maria) and dancer (he excels at Cool), even if he at times struggles to bring his slightly bland character to life. He gives Tony a puppy dog quality – that does make hard to believe this version of the character killed a man in a brawl – as well as a wonderful sense of youthful impetuousness. Opposite him Rachel Zegler – plucked from YouTube by an open casting call – is sensationally wide-eyed, youthful radiance as Maria, naïve and in love, a superb singer.

Even better though are the supporting roles. Finest of all is Ariana DeBose, for whom this film feels like the unearthing of a major talent. Her singing and dancing is awe-inspiring, but it’s DeBose’s ability to switch from warm and motherly, to flirtatious and sexy, to grief, rage and confusion and all of it feeling a natural development from one to another is extraordinary. Her major songs are the films main highlights, stunningly performed. David Alvarez is a passionate, head-strong Bernardo, convinced that he is acting for the best (like DeBose his singing and dancing is extraordinary). Mike Faist is brilliantly surly and enraged (and struggling with repressed feelings for Tony) as Riff.

And, of course, there is Rita Moreno, now playing Valentina, a re-invention of the original production’s character of Don. Moreno worked closely as a consultant with Spielberg and Peck, and gives her scenes a world-weary sadness and desire for hope. She sparks beautifully with Elgort and to see her save Anita from gang rape (still a shocking scene, as it was when Moreno played it) and then angrily spit her contempt and rage at these boys is very powerful.

West Side Story needed to justify its existence. It does this in so many ways. Wonderfully performed by the cast, Spielberg pays homage to the original and classic Hollywood musicals but mixes this with electric film-making and a far greater degree of social and racial awareness (without ever hammering the points home) that allows you to see this tragedy from a new perspectives. It reimagines without dramatically reinventing and sits beautifully alongside the original. It’s more than justified its existence: in many ways it’s even better than the original.