Irish gangsters manipulate a violent but needy boxer in this well-made debut

Director: Nick Rowland

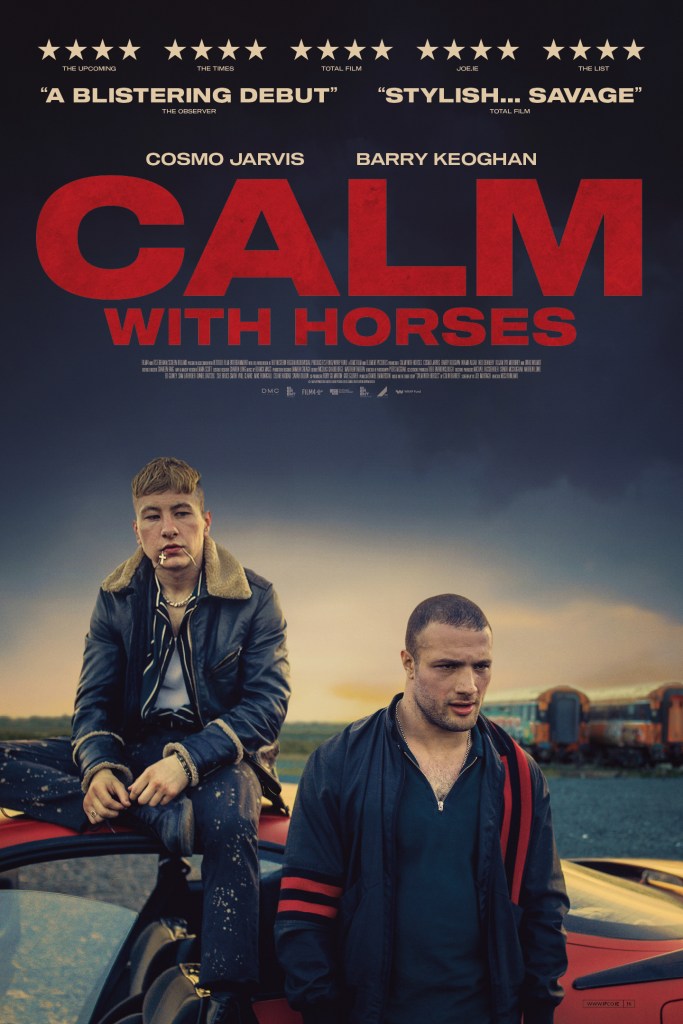

Cast: Cosmo Jarvis (Arm), Barry Keoghan (Dymphna), Niamh Algar (Ursula), Ned Dennehy (Paudi), Kiljan Moroney (Jack), David Wilmot (Hector), Anthony Welsh (Rob), Simone Kirby (Jules)

In rural Ireland a former boxer, Arm (Cosmo Jarvis), has found a new outlet for violence as an gang enforcer. But Arm is, at heart, a gentle soul, and his desire to belong and be part of a “family” is effectively exploited by the gang, especially his weaselly, bullying boss Dymphana (Barry Keoghan) who treats him like an affectionate pet-dog. His ex, Ursula (Niamh Algar), mother to his autistic son Jack, wants him to change his ways or stay out of their lives. But can Arm change?

Rowland’s film has a deliberately seedy quality to it, shot with a grimy intensity and crawling along on its belly among the mud and filth of Irish crime gangs. It’s a thrilling expose though of how crime takes and takes and is never satisfied. It’s turned Arm into a shell, throwing him the odd bone of inclusive comfort, then ordering him out like a rabid dog to hand out another beating to anyone who has crossed the family.

The main target is a man the heads of the family suspect of raping their teenage niece – although whether this was genuine sexual assault or simply a question of perverse family pride is left open. Arm opens the film by handing out a vicious beating – albeit one where he carefully lays out the ground rules with his victim before going about it with a punch-clock sense of duty. It’s what Arm is used for – a not that bright, piece of muscle who, despite his intimidating presence, will do (almost) anything for anyone who makes him feel wanted.

Even if the main person who does is as a dastardly as Dymphana. Keoghan is very good as a snide, insidious small-time crook, who openly calls Arm his dog and fills his head with prejudices and suspicions designed to keep him in his place. If he’s the dark angel, then Ursula is the good one: Algar equally brilliant as a decent, kind, supportive person who has come to the end of her tether with a man who she now feels is a danger to the fragile temperament of her autistic son.

It’s the fate of this son that will penetrate through the dead exterior shell that surrounds Arm, and make him start to question his own life. There is more than a hint that the fragile, timid, surly Arm – beautifully played, with a haunting gentleness under the violent exterior by Cosmo Jarvis – suffers from a similar condition to his son. Like him, he finds rage he can’t control bubbling up inside him (Arm is hopelessly ill prepared for helping his son during Jack’s emotional outbursts). He at times lacks an emotional intelligence to understand how people are treating him and why. It’s something Ursula knows and recognises – and why she gives him as many chances as she does.

Like his son, Arm finds himself calmed by engagement with animals (the title comes from Jack’s therapy sessions, horse riding). He also, buried somewhere in him, has a strong sense of right and wrong and eventually finds the courage to question his orders, as he begins to understand he really belongs not with them but with his ‘true’ family. His motivations shift from simply pleasing his masters to finding the money Ursula needs to move to Cork and place Jack in a special-needs-school, a need for his son that he slowly learns to place above his own wants and desires.

Eventually this explodes into scenes of retributive violence, shot by Rowland with an immersive intensity (there are some particularly uniquely filmed country-lane car-chase scenes, with the camera mounted on the car at an unusual angle). The violence that has lurked only just beneath the surface of the crime family, bubbles savagely to the top as it’s made clear that even the slightest deviation from what the family wants or expects from its enforcer will never be tolerated.

At times, Calm with Horses is a little too reminiscent of other crime dramas: for all its intelligent and skilful construction and playing, there isn’t a lot that feels really original here. Its influences are plain, but what it has is an intelligent empathy for its characters, and their situations, that constantly rewards you. At times, these characters surprise you with how far they will go: at others they disappoint you with their selfishness. But, thanks to the acting and direction, they always feel real.

Calm with Horses is an impressive debut, confident and exciting. Jarvis is superb as an inarticulate, unaware gentle-ish giant, with Keoghan and Algar outstanding in support (both were BAFTA nominated). It’s grimy, matching the dangerous world its set in, but it also has flashes of hope and understanding in it, little moments of calmness that pepper the darkness. It’s a fine crime drama.