One of the first POW films, setting a template for stiff-upper-lip derring-do

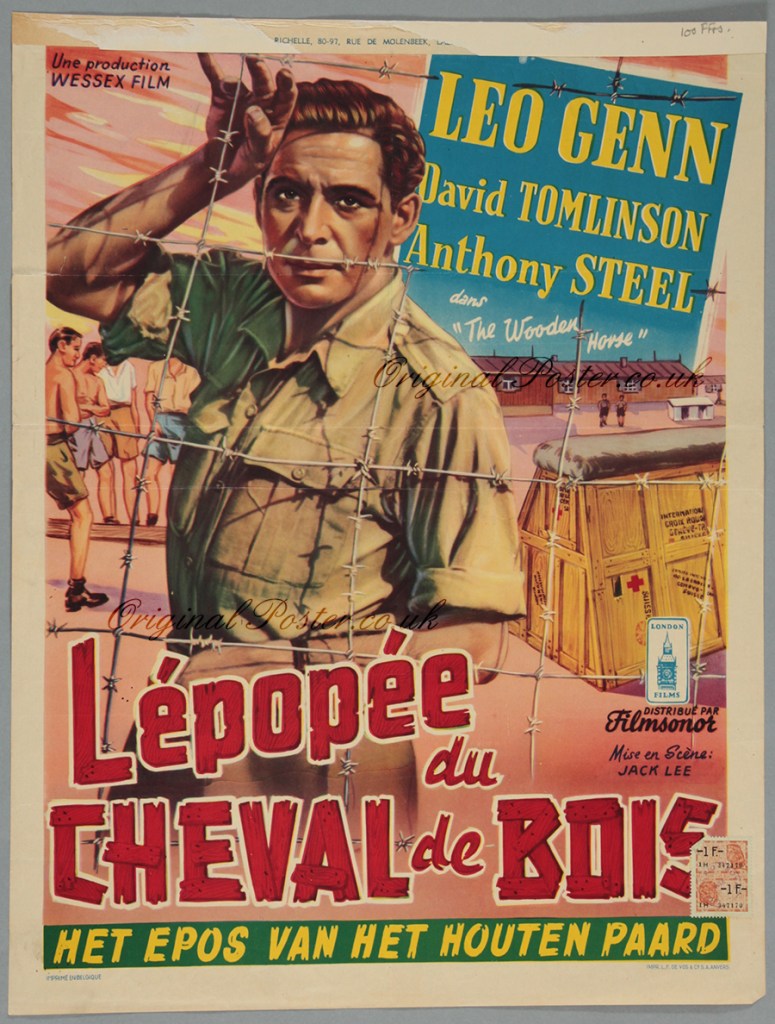

Director: Jack Lee

Cast: Leo Genn (Peter Howard), David Tomlinson (Philip Rowe), Anthony Steel (John Clinton), David Greene (Bennett), Peter Burton (Nigel), Patrick Waddington (Senior British Officer), Michael Goodliffe (Robbie), Anthony Dawson (Pomfret), Bryan Forbes (Paul), Dan Cunningham (David)

One of the most popular of WW2 movies sub-genres is the POW escape movie. The Wooden Horse was one of the first of these, showcasing the sort of barmy, off-the-wall scheme that British POWs spent their tedious years dreaming up. Based on an autobiographical novel by former POW Eric Williams – here fictionalised as Peter Howard (Leo Genn) – inmates of Stalag Luft III built a pommel horse to aid their escape. The scheme? Hide a man underneath the horse to dig a tunnel, while the guards are distracted by a never-ending stream of men jumping over it for hours and hours on end.

The Wooden Horse dramatizes this with a stiff-upper-lip ‘well done Old Chap’ Britishness, shot with a low-key documentary realism (the film blew a huge portion of its budget on location shooting). It’s almost defiantly low-key, about a world away from Steve McQueen jumping over a fence on a motorbike or the sort of emotive struggles with war pressure in The Cruel Sea. Even the escape itself is a grinding, repetitive task taking place over months moving an infinitesimal distance every day as the parade ground tunnel edges closer and closer to the fence. This low-key attitude extends to the cast, led by Leo Genn, who eschew dynamics for calm, quiet unflappability. (Ironically, despite its documentary realism, Peter Butterworth – one of the original members of the escape attempt – was told on auditioning he wasn’t believable as a POW.)

The film is split neatly into two halves. The first covers the escape plan itself and lays out a structure that became familiar from countless POW films that followed: the plan is carefully detailed, senior officers humph and finally flick the thumbs up, a parade of fellow inmates chip in expertise (from forgery to ingenious distractions), a staged accident of flipping the horse over tricks the Germans into thinking nothing is going on, the tunnel caves in, a man is left stranded in the tunnel longer than is safe… It’s all in here, while our heroes bluffly and bravely work out the logistics of smuggling soil away and mastering various French identities to make their escape.

The second half follows two of our heroes – Leo Genn’s stoic Howard and Anthony Steele’s matinee idol Clinton – as they shred their nerves moving through Europe aiming for the port of Lübeck and a ship to Norway. This is the marginally less interesting part of the film, although it conversely does feature the film’s most interesting moment as a visibly sickened Clinton is forced to kill an ordinary German guard, very different from the usual boys-own adventure attitudes you expect.

However, most of the rest of the second half is just a little too dry and documentary, despite the best efforts to play up the paranoia and tension of a life on the run in occupied territory. Lee directs with a methodical, unflashy style, while ongoing clashes with producers on the budget, which eventually saw the film completed months later by the producer and a hurriedly put-together rather abrupt (and incongruous) ending in a Swedish restaurant, which seems to lean into the beginnings of an anti-Soviet Cold-War era consensus. Some of the dramatic tension drains out of a film which actually might have benefited from a little more melodrama, among the muttered, patient conversations in alleyways and the almost-agitated debates about which resistance groups to trust.

The camp-escape half works best, probably because the ingenuity of seeing the prisoners work out the logistics of converting their pommel horse into the perfect escape weapon and overcoming the minutia of camp life remains very entertaining. There is even a certain amount of wit in the bonhomie and cheek of the escape, which the film doesn’t shy away from, from the plan depending on the willingness of hungry POWs hurling themselves over a wooden horse for hours at a time to the boarding school air of bored over-familiarity that permeates the sleeping quarters. Lee also mines some tension out of a late-night inspection of the sleeping quarters, which only just misses discovering the mountains of soil that has been hidden precariously in the ceiling.

The Germans themselves are presented fairly sportingly – The Wooden Horse doesn’t give us an obvious villain and, as noted, presents its only slain German as a tragic figure. The Germans are even fairly sporting, solemnly carrying away the offending horse with a hurt dignity after the escape – presumably the poor War Horse is to be confined to solitary – while the POWs give this hero a rousing cheer. The Wooden Horse avoids the set-up of many similar films, which often presents both a token ‘Worthy Opponent’ and a token ‘Unrepentant Nazi’ among the Germans. Instead, they are exclusively presented as straight-forward professionals – again perhaps with an eye on the emerging 1950s anti-Soviet consensus that was starting to form in Europe.

The mood of sporting endeavour around the whole film – as well as the stiff-upper-lip pluck of the imprisoned Brits – helped guide the POW film towards its natural development as a Boy’s-Own adventure story with a sense escape as the ultimate sporting adventure (though even The Great Escape throws in more than enough tragedy). The Wooden Horse sometimes lacks in drama, so swept up is it in a sort of documentary realism (it’s hard not to argue with the producers that the put-upon forbearance of John Mills might have been a better choice for the lead than the rather too smooth Leo Genn), but as an early example of a much-loved genre it offers more than enough entertainment.