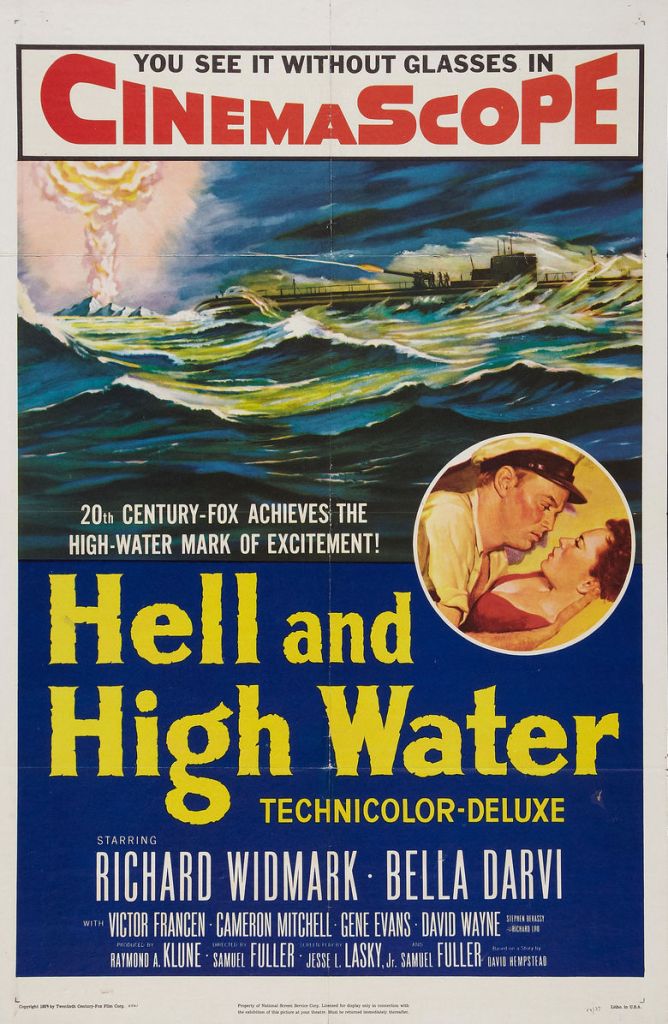

Action below the waves in this dutiful, for-the-money thriller from Samuel Fuller that lacks imagination or freshness

Director: Samuel Fuller

Cast: Richard Widmark (Captain Adam Jones), Bella Darvi (Professor Denise Gerard), Victor Francen (Professor Montel), Cameron Mitchell (“Ski” Brodski), Gene Evans (Chief Holter), David Wayne (Tugboat Walker), Stephen Bekassy (Neumann), Richard Loo (Hakada Fujimori), Wong Artarne (Chin Lee), Henry Kulky (Gunner McCrossin)

Few films start with a bigger bang than Hell and High Water: a nuclear explosion. What caused it? The film winds back to tell us. Retired submarine captain Adam Jones (Richard Widmark) is hired by a cabal of intellectuals and scientists working to maintain world peace. Somewhere on an island off Japan, the Commies are working on a secret nuclear bomb. Jones – in return for a fee – will shuttle Professors Montel (Victor Francen) and Denise Gerard (Bella Darvi) to investigate. Cue submarine duels, personality clashes, romance and shoot-outs.

To be honest, nothing in Hell and High Water lives up to that bang at the start. Samuel Fuller took on the film as a favour to producer Darryl F Zanuck, but had a low-opinion of the result (labelling it his worst film). Fuller rewrote the script, added a lot of his compulsive drive to the direction and handled it well – but it feels like a “gun for hire” film. Goodness only knows what Fuller made of Spielberg telling him in 1979 he loved it so much he carried a print of it in his car (perhaps “Have you not seen Pickup on South Street?”)

Hell and High Water is a serviceable men-on-a-mission film that sneaks in a few interesting beats, but otherwise goes for well-shot action and predictable events over invention and insight. It’s anchored by a grumpy Richard Widmark (who thought the script was crap and co-star Darvi couldn’t act) as a hard-to-like hero. Never-the-less Jones’ ruthless mercenaryism is the film’s most interesting beat – even if it is a repeat of the same actor’s attitude in Pickup on South Street, right done to mouthing almost the same contemptuous line about ostentatious flag wavers. Jones does his job professionally – and he’s got no truck with his country being dishonoured or attacked by Commies – but his main concern is always the $50,000 fee he’s been promised.

Also paid off are the whole crew who, in the film’s other interesting beat, are a regular united nations all of whom treat each other with equality and respect (the only people not represented here are Black people). We’ve got a German, a Japanese, a Frenchman, several Americans – considering only nine years previously all these nations had been working over-time to kill each other, it’s great to see the team on the ship working as a tension free-unit. We even have a Chinese sailor – who entertains his fellow crew with improvised ditties – becoming a crucial hero.

Fuller also shoots the sub action – a mix of models and trick photography – very well. The angles he uses of the subs underwater, in particular their turns, and the sweaty look of those underwater (and the increasing tensions) influenced several future films. All the submarine lingo you’d expect is trotted out with real commitment (“Right full rudder!”) and every box is carefully ticked, from sinking the bottom, to the costly rush to close a bulkhead. The torpedo fights are well-staged and whenever the film dives it’s at its best.

Where it is less so is whenever the film dwells on its characters. It tries to push the envelope a bit by introducing a female professor who is assured, competent, super-smart and gets stuck in with helping out when things go pear-shaped. She’s played by Bella Darvi, a protégé (and more) of Zanuck, who he was determined to elevate to stardom. Despite Widmark’s criticism, she’s fine here, even if she struggles to convey the charisma the role needs, often falling back on slightly grating over-earnest, head-girl smartness. What fails is the complete lack of chemistry between her and Widmark, their half-hearted, dutiful romance (probably mostly Widmark’s fault).

You’ll feel sorry for her though as the crew – and Jones – eye her up like a piece of meat when she arrives. Of course, this dated sexual leering is par for the course, but is still more than a little uncomfortable. But this is still the era when a sailor taking his top off to push his tattoos into a woman’s face was funny rather than a crime. The film does gives Darvi’s Professor a lot of proactivity and does generally take her side – even if she, inevitably, needs to learn our hero knows best.

Hell and High Water charges through to a decent ending, with just the right mix of self-sacrifice, tension and pay off. Victor Francen gives the films best performance as an illustrious, brave French scientist. But it never feels like anything more than a dutiful, for-the-money film. There is none of Fuller’s fire or feeling here, no real imagination or freshness in the ideas or concepts. It hits all the beats, ties things up with a bow and sends you home – but its very hard to really remember anything distinctive about it when the credits roll.