Alexander Payne’s hilarious Christmas-themed prep school drama is a heart-warming delight

Director: Alexander Payne

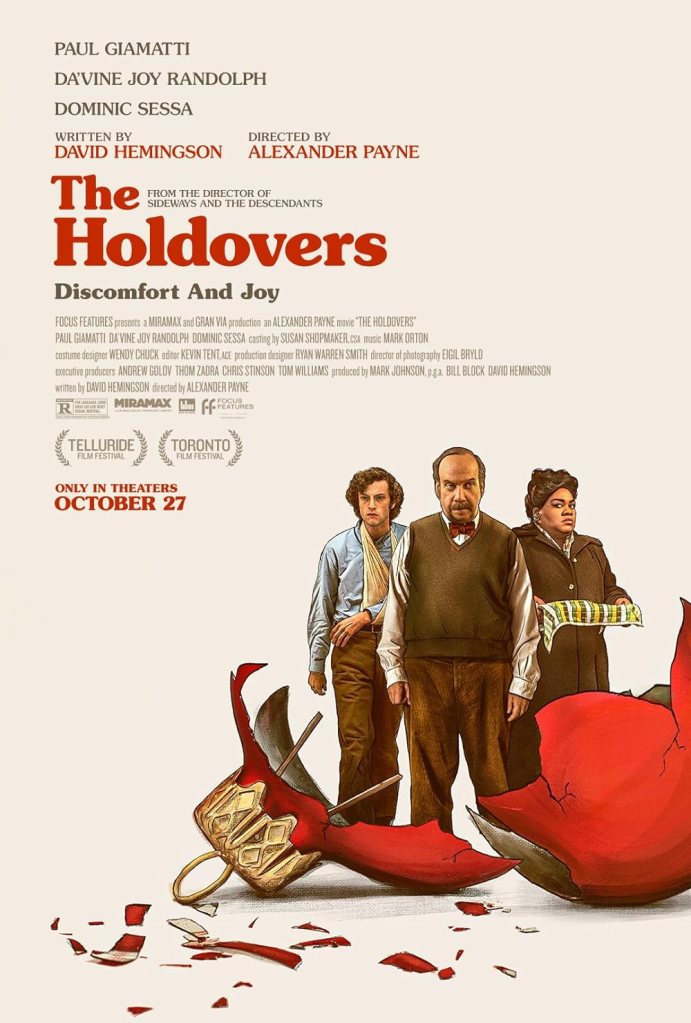

Cast: Paul Giamatti (Paul Hunham), Dominic Sessa (Angus Tully), Da’Vine Joy Randolph (Mary Lamb), Carrie Preston (Lydia Crane), Brady Hepner (Teddy Kountze), Ian Dolley (Alex Ollerman), Jim Kaplan (Ye-Joon Park), Michael Provost (Jason Smith), Andrew Garman (Dr Hardy Woodrup)

Christmas is a time when people come together – not always by choice. In 1971, Paul Hunham (Paul Giamatti) is a curmudgeonly classics teacher at Barton Academy, a New England boarding school for the wealthy which he once attended himself on a scholarship. He’s despised by teachers and students alike for his waspish wit, brutal marking and abrasive personality. As a punishment for refusing to give a donor’s son the grade needed for Princeton, Hunham must spend Christmas with “the Holdovers”, the students whose families cannot take them for Christmas. Principal among these is Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa), while Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) the campus cook whose son (a former scholarship student at the school) was killed in Vietnam also remains on site. These three difficult, damaged people surprise themselves and each other as time together thaws each of them.

I found this film an absolute delight, funny, heartwarming and rather moving, a treat for any time of the year. Shot and edited with a deceptive simplicity, it’s only when you think back that you realise every scene was perfectly formed, every beat wonderfully timed and not a frame was wasted. This is serene film-making that never draws attention to itself. Payne textures the film like a missing 70s auteur piece – like other parts of his work there are strong elements of Hal Ashby, not least The Last Detail – and his measured, patient staging makes the moments of waspish or foul-mouthed humour land with as much impact as quiet moments of raw pain.

What’s really striking about The Holdovers is the warmth and regard it has for its three characters. Lesser films would set them up as standard tropes: people whose edges would be worn off due to the magic of reaching out to others. What The Holdovers does really well is establish from the start that, depressed and damaged as they are, they are all at heart kind, decent people. Paul’s hostility to his students stems from disgust at their entitlement – we’re completely with him when he hits the roof at the contemptuous “get over it” attitude one student shows to the grieving Mary. Mary’s motherly instincts express themselves in myriad ways. And Angus’ sardonic, smart-aleck waspishness doesn’t stop him comforting a vulnerable younger student.

To make this work as well it does, the acting is key and in its principals The Holdovers is blessed. Paul Giamatti is superb as the prickly Paul, who at first even we can find challenging. Like a bullying Mr Chips, Paul sets tests for Christmas, orders the holdovers to exercise and study during vacation and delights in insulting his students. But Giamatti slowly shows this is a shield for a man disappointed with life, who feels its injustice and imbalance very keenly and decides it’s best to attack life head on.

Paul is a man who really, really cares – so much so, that it’s easier to never allow himself to get close to anyone. Giamatti balances this heartfelt humanity with perfectly pitched comedy. Paul’s acidic put-downs, layered with dense classical references, are frequently hilarious but it’s also rather touching to see him trying to use the same references to try and spark small-talk with strangers (unfortunately the etymological origins of Santa Claus in Ancient Greece leave his audience baffled.). You believe him when he talks about finding the world a bitter and complicated place just as you can understand why he feels he has to respond in kind.

You can also understand why he starts to see the same traits in Angus Tully. Played with a wonderful naturalness by Dominic Sessa (in his film debut), Angus also uses humour and intelligence as a shield. Both he and Paul are sharply intelligent (Paul even grades Angus a B!), disgusted by the casual superiority of Angus’ classmates (in particular the awful – and surely not accidentally named – Kountze) and turn out to be all-but orphans struggling with the same depression. What’s delightful about Sessa’s performance though is he manages to show Angus is still just a kid – he can be vulnerable, moody but also innocent: he’s breathlessly excited when flirting with a girl at a party and bounds off to pack his bags with a whoop when Paul agrees to take him on a “field trip” to Boston.

Angus and Paul are surprising kindred spirits. They both stretch the “Barton men do not lie” mantra to the limit in a series of minor crises, from a hospital visit to a prevented barroom brawl to a meeting with Paul’s puffed up former Princeton schoolmate. The Holdovers also, refreshingly, avoids creating cheap melodrama between them. Promises that certain facts will remain entre nous are loyally kept, making the film’s close (with developments we could have an anticipated at the start) feel true.

The bridge these two meet across is Da’Vine Joy Randolph’s wonderfully warm yet brittle performance as a loving woman lost in grief. Mary had clearly focused every hour on her son since his birth, his death leaving her bereft. Around her house, his possessions are stored like mini-shrines. Mary keeps up her professionalism while screaming in agony on the inside, but she’s still determined to see the best in people. All three actors are astonishingly good.

The Holdovers sparks these actors off each other in a series of scenes that are, in turn, hilarious, surprising and then, from nowhere, deeply moving. It’s a lovingly optimistic film at heart. Except for Kountze and the headmaster, every character is deep-down decent (the holdover who spontaneously – and excitedly – invites his fellow holdovers to a skiing holiday is adorable). It’s a film that finds this good in people without being cloying, possibly because the characters puncture any sentimentality with a well-timed, foul-mouthed quip. It also swerves away from predictable tropes (despite Payne cheekily teasing more than a few) to create a sense of a story that feels true.

The Holdovers is also rare in American films for taking class as a strong theme. Barton is a sort of finishing school for the rich, where the size of the library a benefactor buys is more important than the academic skill of his son. Paul is, rightly, appalled by the casual assumption of superiority of many of the students, and their smug obliviousness to their privilege. Mary’s son, due to not being able to afford college, was condemned to enlistment in Vietnam in the hope of a GI bill education. Paul’s past misfortunes are steeped in class injustice and Payne frequently stresses the plush comfort of the school compared to the working-class town it sits inside. There is something quite British about this sharp-eyed look at a “classless society”.

The Holdovers is an intelligent but also magnificently heart-warming film with just the right touch of lemony bittersweetness. With three gorgeous performances, Payne’s film superbly shows how the defences we use to protect ourselves can hurt us as much as those around us. Avoiding sentimentality, it concentrates on making us care deeply for its three damaged souls as they stumble towards understanding. It does this with sensitivity, empathy and (perhaps most importantly) a lot of humour. The Holdovers is a small-scale triumph, the sort of film I can imagine watching again and again and always bringing a small tear to the eye.