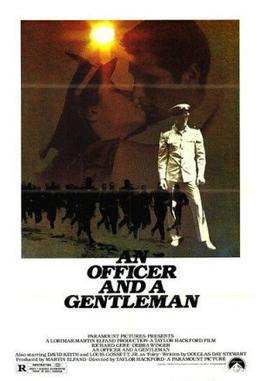

Classic 80s romance? Or is it, in fact, a searing kitchen-sink drama about class and depression? One of the great mis-remembered films of all time

Director: Taylor Hackford

Cast: Richard Gere (Zach Mayo), Debra Winger (Paula Pokrifki), Louis Gossett Jnr (Gunnery Sergeant Emil Foley), David Keith (Sid Worley), Lisa Blount (Lynette Pomeroy), Robert Loggia (Byron Mayo), Lisa Elbacher (Casey Seeger), Tony Plana (Emiliano Santos Della Serra), Harold Sylvester (Lionel Perryman), David Caruso (Topper Daniels)

An Officer and Gentleman is remembered as a sweep-you-off-your-feet romance, with power-ballads underplaying attractive Hollywood stars passionately proclaiming their love. It ain’t anything like that. This proto-Top Gun – a film it has strong similarities to in structure and design – is actually a kitchen-sink drama masquerading as a feelgood movie, with a final romantic image and “Up Where We Belong” leaving a deceptive memory behind. Where Top Gun is loud, brash and fundamentally reassuring and straight-forward, An Officer and a Gentleman is jagged, surprisingly difficult and unsettling. Put it this way: Tom Cruise doesn’t call anyone the c-bomb in Top Gun.

Zach Mayo (one of Richard Gere’s legendary performances, the memory of which guided much of the rest of his career far more than its reality) is a Navy-brat determined to be nothing like his alcoholic, whoring dad (Robert Loggia). He’s going to graduate from Naval Flight Candidate school and become “an officer and a gentleman”. Zach is a damaged soul, defensive, closed-off and selfish, a smarmy, cruel loner interested only in what he can get out of any relationship. The film is about whether Zach will learn to become a sympathetic, caring person, rather than a resentful douche.

There are three influences that might just change him. Firstly, fellow trainee Sid (David Keith), from a Naval officer family, attending because his deceased brother can’t. The second is training officer and uncompromising disciplinarian Sgt Emil Foley (Louis Gossett Jnr). And, finally, factory worker Paula (Debra Winger), one of the local women officer candidates are warned are intent on bagging a husband by fair or foul. Each will play a different role in making Zach a fully rounded person.

Hackford’s film is a tough, hardened one that takes a long hard look at mental health, guilt, suicide, parental resentment and a host of other complex issues. Any romantic moment is matched with one of pain, fury or characters doubled over with guilt and shame. It dives deep into its flawed hero and shows how someone can, almost unwittingly, be reconstructed into something warmer. It does all this in grimy, scruffy settings with characters making desperate choices motivated by poverty and lack of choices.

It opens with a shaggy-haired, scruffy Gere starring into a mirror in a dark motel room while his father is passed out in bed with two prostitutes. We are constantly reminded of Zach’s working-class background, his life growing up trailing behind his (largely indifferent) father after the suicide of his mother, left to fend for himself in the rough and tumble of the Philippine streets. At naval school, the same chippy resentment of how people perceive his roots persists – along with the lessons he has spent his whole life learning: that he should count on no-one but himself.

Zach doesn’t believe he’s worth loving. Facing abandonment issues (of different kinds) from both his parents, he doesn’t give a toss about anyone and expects them to feel the same. He sets up a grift selling pre-polished buckles and boots to his fellow candidates, only helping them for a price. He completes exercises alone, cheats in aeronautical class, and gloats as he passes anyone on physical trials. When dating Paula, he frequently retreats into cold rudeness when conversation turns to anything emotional, and repeatedly claims he wants nothing more than a bit of fun. It all stems – as Paula realises – from a defensive hostility, pushing people away before they can leave him.

His lack of team-playing is identified early by Foley as his Achilles heel. Louis Gossett Jnr won an Oscar for his impressively nuanced work here. At first Foley seems an almost unbelievably horrible man, a bully dropping racist and homophobic slurs with casual ease, who makes it his mission to drive his candidates out of the programme (right down to bragging that he chisels a mark on his swivel stick whenever another one drops out).

However, Hackford and Gossett Jnr skilfully show this is, to a degree, a show: Foley is tough because the military is tough, and deep down he does care. Candidates slowly earn his respect (female candidate Seeger may fail to climb a wall, but goddamn he respects her guts) and he quietly goes to great lengths to support them. Foley’s act is intended to get them to excel – and he’ll be proud of them when they do, just as they will be grateful to him. The strength of Gossett Jnr’s performance mean his scenes dominate the narrative (at the cost of the romance), but this is to the film’s benefit.

Interestingly, that romance is often the least effective part of the film. Gere and Winger have fine chemistry (despite, allegedly, not getting on) but the narrative often takes sudden time jumps. From one scene to another they’ll go from together to split up, and the film never quite manages to show us naturally how this is changing Zach. Instead, it frequently stops to tell us this, with on-the-nose conversations. Winger is good, but the relationship feels forced – as if it a film couldn’t exist without a romance, when actually Paula could be removed altogether and it wouldn’t really change the film.

It’s forced perhaps because what really feels like it changes Zach is the friendship with Sid. Played very well by a sensitive David Keith, Sid is everything Zach is not. Confident, happy to help others, a natural leader and team player. Under the surface he isn’t – doubtful and insecure – but the friendship between them is the spark that changes Zach. Sid is, much like Goose in Top Gun, the sacrificial pal, but this sacrifice promotes real growth in Zach. The parallel romance between Sid and gold-digger Lynette (a fine Lisa Blount) is also an effective commentary on Zach and Paula, both characters being mirror images of the leads.

The film culminates in that romantic sweep-you-off-your-feet moment in the factory: but that feels like it belongs in a different film than the hard-boiled one we’ve been watching of a man confronting his fear of failure and lack of self-worth. Gere, by the way, is very good as Zach – his smirk a defensive screen for a host of psychological problems (few actors would have been willing to be as unlikeable as Gere is here). An Officer and a Gentleman is really a character study in working-class resentments, but somehow is mis-remembered as the quintessential 80s romance. It truly isn’t. Instead Hackford’s film – flawed as it is – is smarter and pricklier than that.