Ultimate arthouse film, designed to reward constant analysis and interpretation with no answers

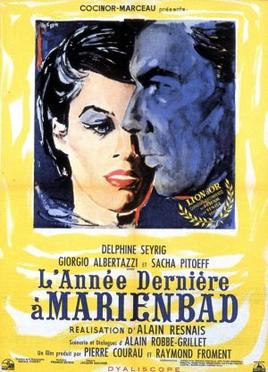

Director: Alain Resnais

Cast: Giorgio Albertazzi (X), Delphine Seyrig (A), Sacha Pitoëff (M)

If there is one film that could practically stand as a dictionary definition of art-house cinema, it might be Last Year at Marienbad. A striking collaboration between director Alain Resnais and novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet, is puts the vague in Nouvelle Vague (French New Wave to you and me). Last Year at Marienbad is a film almost unlike any other, a work of art that lays itself out in front of you and asks you to bring your own viewpoint to bear to decide what (if anything) it’s actually about. You could call it a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma (to borrow a phrase from Churchill – and lord knows what he would have made of it).

Last Year at Marienbad is set in a sprawling, Versailles-like palace (which might be a hotel), where grand, art-laden corridors go on forever, every room drips with fine details the grounds are mini-countries and opulent, geometric designs fill ever corner of the building. Within this, a parade of people dressed in evening finery move like impassive robots, uttering flat banalities and either moving slowly between rooms or standing impassively like statues. Among these strange, ghost-like figures a man (Giorgio Albertazzi) waylays a woman (Delphine Seyrig) and tells her a year earlier they met somewhere else (possibly Marienbad, but could have been Frederiksbad, Karlstadt or Baden), fell in love and planned to elope a year later. She doesn’t remember him at all. He spends the film trying to persuade her. Another man (Sacha Pitoëff), who might be her husband, engages the first in a mathematical card game (nim) which he defeats him at constantly.

If that sounds sparse, it’s because a plot description barely functions for a film so wilfully oblique it’s about whatever you decide it’s about. Resnais and Robbe-Grillet’s purpose perhaps can be seen when our two could-be lovers discuss a classical statue. (In a neat touch, the statue itself was specially carved for the film). Their conversation revolves around different interpretations of what these Roman (or Greek) figures are doing: is the man protecting the woman from walking into danger? Is the woman protecting the man? Are they in love? Are they arguing? Why is there a dog sitting at her feet, looking away? This conversation is framed through a series of lingering shots from multiple angles, that invite us to bore our eyes into the statue and decide for ourselves.

And that’s basically the film in microcosm. It’s a series of beautifully haunting images and scenes, shot by a gliding camera and accompanied by Francis Seyrig’s hypnotic score, that invites the views to stare at this film like they would a painting in a gallery and spot as many (or as few) tiny details as they like and see if it changes their view of the artist’s overall intention. Last Year at Marienbad, in effect, nearly defies any sort of logical criticism. What you take out of depends entirely on what you put in. Which is to say, it’s as perfectly legitimate to say it’s a pile of pretentious, piss-taking piffle as it is to call it a gorgeous, transcendent piece of art that leaves you thinking for days.

Everything is designed to leave things open to question, with the normal rules of logic and cinematic structure routinely discarded. Characters will be in frame at the start of the shot and then, as the camera drifts away from them, suddenly appear in another (impossible) location – for example one shot starts with X at a card table, then drifts across the room to the doorway to see him enter.

The people move like functional props, or bored actors trotting through their marks. There is barely a facial expression or jot of intonation in anyone. They stand mutely to attention, or shift through a senseless parade of conversations, waltzes and card games. There is a ghostly, dream-like, never-world quality to the entire hotel (it’s influence on The Shining – from Resnais’ controlled, Steadicam style shots, to the haunting sense that mankind has no agency or influence in the building – is really clear). It’s as cold as a block of marble, and the people often feel like statues that have walked off their pedestals into the world.

Locations are inconsistent and change all the time: Resnais shot the film in multiple palaces and stitched the locations together, hiding cuts with carefully placed objects (in one instance A walks down a corridor seemingly in one shot, but Seyrig is actually walking through about three totally different locations). The pattern, design and contents of rooms change (A’s bedroom shifts through myriad designs and layout, most noticeable in its constant swopping between either a mirror or a painting above the mantelpiece). An exterior balcony next to that statue subtly changes location as well (and even appears as a detailed landscape painting).

Everything shifts, twists and contorts all the time as if the film reforms depending on the angle you are looking at it from. The hotel could be a purgatory or a dream. It could be a half-formed memory. X could be an Orpheus striving to save his Eurydice. Or a self-aware film character. Or a trapped dead soul. A could be an amnesiac, a fantasy figure, a ghost, a part of X’s psyche. M could be her husband, X’s alter-ego, death or a complete stranger. Every single interpretation is legitimate and you could pull out different moments to support any one of them.

Myself, I saw it as like a dive into X’s memories. Everything about the shifting scenery, strange dis-jointed logic of the film moving seemingly at random between past and present, the repetitions and reframings of the same conversations, seemed like a man sifting his memories. X even stops and argues against certain scenes (‘It didn’t happen like that.’) There are hints of a dark trauma: repeated shots of A cowering in her room, brief moments of shock, tears and her pulling away from X. We see multiple hints of A’s death, including a possible shooting by M. I started to think this was X reframing his memories to absolve himself: that after rejection by A, he assaulted her in some way, she committed suicide (the opening play the characters are watching is Romers based on Ibsen’s play about a man haunted by the suicide of his wife). X is now forcing his memory to adjust this into a tragedy where he was the victim – and as part of that must persuade A she loved him.

But that’s just my view. You could just as well say X is so bored watching Romers, he makes up a whole fantasy based on it to keep himself entertained (inevitably, the set of the play changes completely whenever we see it). I do think it interesting most 60s criticism took X completely at his word as a victim, while more recent criticism has often cast X as an unreliable narrator (if that term has any meaning here). What matters more is whether you are intrigued enough to find dwelling on what this all means (the way we dwell over a Picasso) worth your time. For me it unquestionably is.